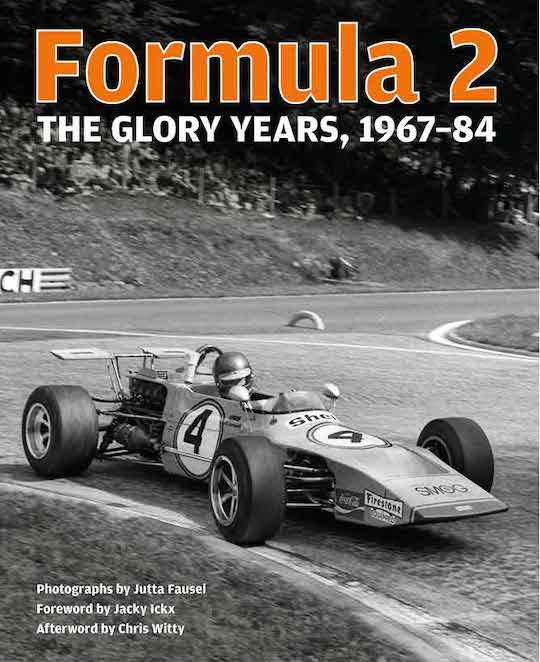

Formula 2–The Glory Years, 1967–84

by Jutta Fausel

by Jutta Fausel

“Of course we all wanted to win but not winning was not a drama.”

—Jacky Ickx, 1967

Formula 2 had existed in various forms before 1967, but its golden era started then, a year after Formula 1’s own “Return to Power.” Thanks to the glut of obsolete Cosworth DFVs in F1’s first turbocharged era, Formula 2 was superseded by F3000 in 1985. Twenty years later, F3000 was replaced by GP2, which might have made more sense if there had been a GP1. But although the disgraced Flavio Briatore tried to create GP1 in 2012, the title still only relates only to a video game. There’s more, because in the same year, 2012, an FIA-sanctioned Formula 2 appeared as a junior single seater series but it lasted only a season. Still with me? Good, because in 2017 the FIA had an attack of common sense and rebranded GP2 as—yes!—Formula 2.

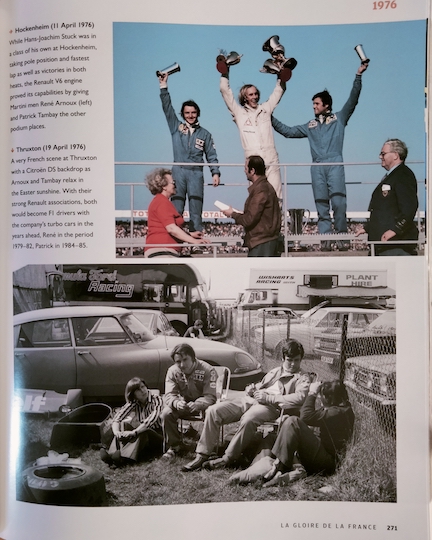

This book is officially about Formula 2’s Glory Years, and that isn’t just nostalgia speaking. In 2025, F2 (as I’ll now abbreviate the series) will race at 14 Grand Prix weekends as the support act to Formula One. Sounds good, huh? But F2 is actually the Suki Waterhouse or Sabrina Carpenter to F1’s Taylor Swift because it’s the support act hardly anybody has come to see. But it wasn’t like that in the glory years. Back then, F2 drew huge crowds, such as the 120,000 at a 1976 Hockenheim race, and, when it did share a stage with F1, F2 could forget it was supposed to be the support act. At the 1967 German Grand Prix, which used F2 cars to pad out a thin F1 grid, Jacky Ickx qualified his Matra MS5 Cosworth an astonishing third, to the chagrin of most of the Formula 1 establishment.

This book is officially about Formula 2’s Glory Years, and that isn’t just nostalgia speaking. In 2025, F2 (as I’ll now abbreviate the series) will race at 14 Grand Prix weekends as the support act to Formula One. Sounds good, huh? But F2 is actually the Suki Waterhouse or Sabrina Carpenter to F1’s Taylor Swift because it’s the support act hardly anybody has come to see. But it wasn’t like that in the glory years. Back then, F2 drew huge crowds, such as the 120,000 at a 1976 Hockenheim race, and, when it did share a stage with F1, F2 could forget it was supposed to be the support act. At the 1967 German Grand Prix, which used F2 cars to pad out a thin F1 grid, Jacky Ickx qualified his Matra MS5 Cosworth an astonishing third, to the chagrin of most of the Formula 1 establishment.

Rumors of a definitive history of F2 have been circulating online for years, usually involving the respected journalist and sometime team owner Chris Witty. So, is the long wait now over? The answer is . . . “well (sigh) sort of . . . but maybe not really.” Witty has indeed contributed to the book, but only the six-page Afterword, and Jacky Ickx has written the two-page Foreword, because the essence of this 560-page book is a season-by-season photographic account. Each chapter starts with a summary of the year and ends with a one-page profile of the year’s F2 champion, and a results table (from which I learned that 58 drivers raced F2 in 1967).

Rumors of a definitive history of F2 have been circulating online for years, usually involving the respected journalist and sometime team owner Chris Witty. So, is the long wait now over? The answer is . . . “well (sigh) sort of . . . but maybe not really.” Witty has indeed contributed to the book, but only the six-page Afterword, and Jacky Ickx has written the two-page Foreword, because the essence of this 560-page book is a season-by-season photographic account. Each chapter starts with a summary of the year and ends with a one-page profile of the year’s F2 champion, and a results table (from which I learned that 58 drivers raced F2 in 1967).

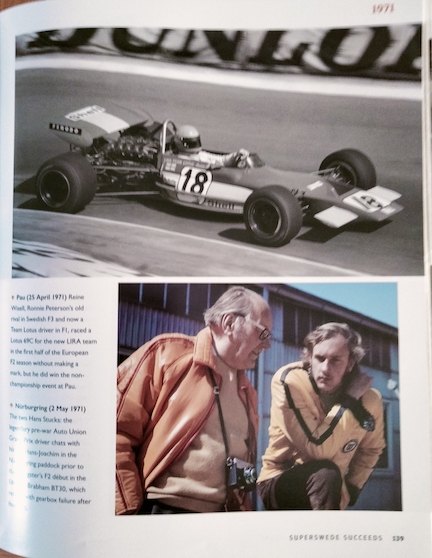

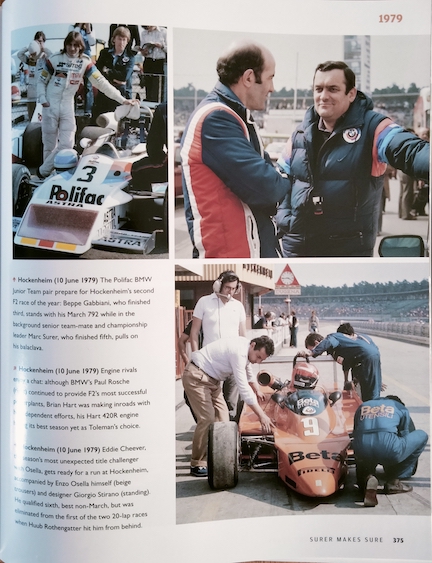

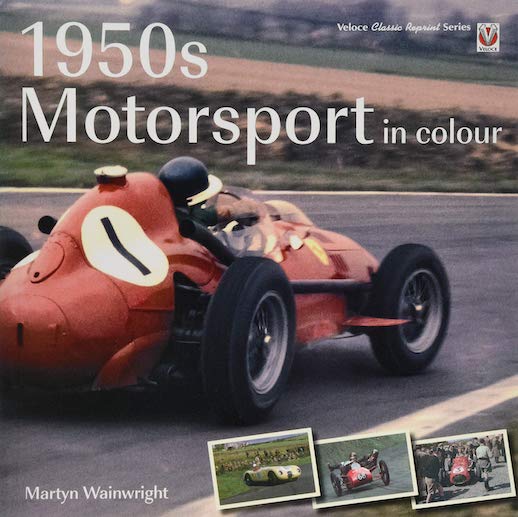

Jutta Fausel’s photographs form the backbone of the book. An escapee from Communist East Germany in 1961, she saw her first race at Solitude later the same year: “I was hooked. I knew this is what I wanted to do.” And she has taken a lot of photographs, no fewer than 900 of which are reproduced in the book. Many, and perhaps more than I expected, are in black and white. That is not a problem per se, but monochrome pictures do need to be enlivened at least with metaphorical color. There are some gems here; I loved the pictures of forgotten circuits like Enna-Pergusa, Tulln-Langenlebarn, or Hameenlinna. However, there are too many formulaic pitlane and grid shots, while the depictions of track action can feel flat, lacking the sparkle and wit of Rainer Schlegelmilch’s work of the same era.

As I have come to expect of Evro books, the overall look and feel of this book exudes quality. And although there is a glossy dustcover, I think the book looks much classier without it.

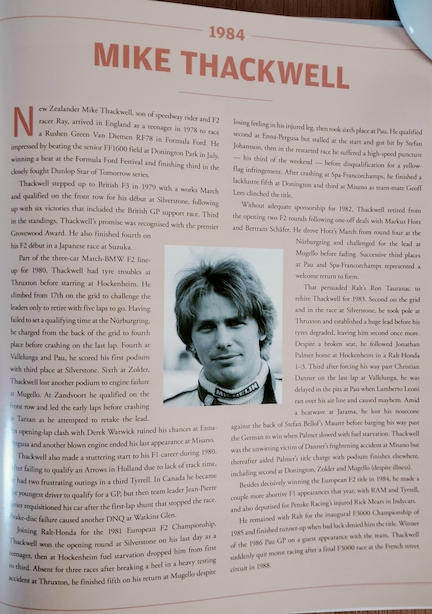

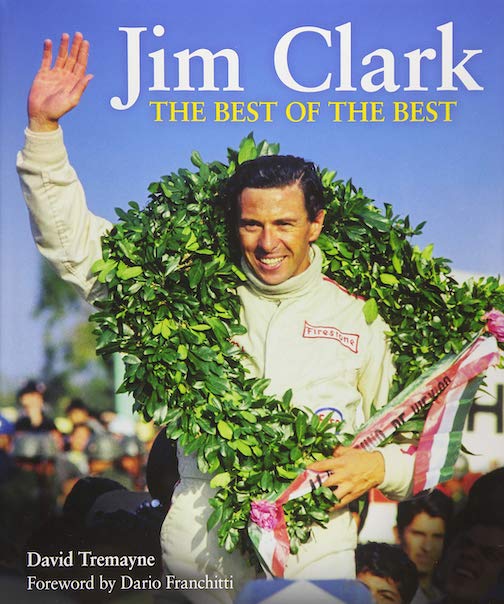

Success in lower formulae is not always a reliable indicator of Formula 1 form—for every Ayrton Senna or Lewis Hamilton there’s an underachieving Dave Walker or Jan Magnussen. With this in mind, the book prompted me to reflect on the later careers of the seventeen F2 champions in the 1967–84 era. Eleven never won a Grand Prix but, of the six who did, Ickx, Peterson, Regazzoni and Arnoux had thirty victories between them. And yet fine drivers such as Hailwood, Thackwell, and Jarier were destined never to take the podium’s highest step, or even the lowest in the New Zealander’s case. Unlike modern F2, established F1 drivers were regular contestants, and often winners in the formula. The grading system prevented F1 stars from scoring points in F2, but starting money and the opportunity to race was sufficient motivation to compete in the junior series. The illustrations depict many F1 “names” enjoying themselves in F2, with Jochen Rindt and Graham Hill having regular drives in the series. And Jim Clark, who is depicted in the poignant images taken at Hockenheim on 7 April1968, shortly before he was killed in his Lotus 48.

Success in lower formulae is not always a reliable indicator of Formula 1 form—for every Ayrton Senna or Lewis Hamilton there’s an underachieving Dave Walker or Jan Magnussen. With this in mind, the book prompted me to reflect on the later careers of the seventeen F2 champions in the 1967–84 era. Eleven never won a Grand Prix but, of the six who did, Ickx, Peterson, Regazzoni and Arnoux had thirty victories between them. And yet fine drivers such as Hailwood, Thackwell, and Jarier were destined never to take the podium’s highest step, or even the lowest in the New Zealander’s case. Unlike modern F2, established F1 drivers were regular contestants, and often winners in the formula. The grading system prevented F1 stars from scoring points in F2, but starting money and the opportunity to race was sufficient motivation to compete in the junior series. The illustrations depict many F1 “names” enjoying themselves in F2, with Jochen Rindt and Graham Hill having regular drives in the series. And Jim Clark, who is depicted in the poignant images taken at Hockenheim on 7 April1968, shortly before he was killed in his Lotus 48.

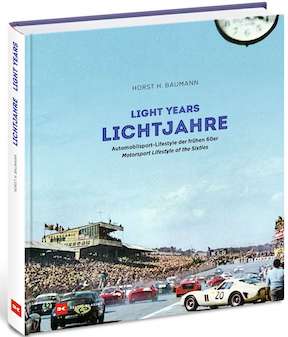

I did enjoy reminding myself just how many different chassis and powertrains were used in F2. Some, like the March 712M and BMW M12 engine, were serial victors, but others, well, not so much. The Holbay-developed straight-six Abarth and the bubble-screened Protos were barely discernible flashes in the pan. Not that this matters much, or even at all, because it was F2’s glorious diversity of shapes and sounds that made it so appealing. And I doubt if any single-seater formula has given birth to cars as consistently pleasing to the eye (or just plain sexy!) as F2 cars, whose proportions were often an exquisite balance between delicacy and potency. From the lovely, cigar-shaped Brabham BT23 in 1967 to the V6-powered Ralt RH6/84 Hondas in the series’ final year, F2 cars never looked anything other than stunning, as page after page (after page!) of imagery reminds us.

I did enjoy reminding myself just how many different chassis and powertrains were used in F2. Some, like the March 712M and BMW M12 engine, were serial victors, but others, well, not so much. The Holbay-developed straight-six Abarth and the bubble-screened Protos were barely discernible flashes in the pan. Not that this matters much, or even at all, because it was F2’s glorious diversity of shapes and sounds that made it so appealing. And I doubt if any single-seater formula has given birth to cars as consistently pleasing to the eye (or just plain sexy!) as F2 cars, whose proportions were often an exquisite balance between delicacy and potency. From the lovely, cigar-shaped Brabham BT23 in 1967 to the V6-powered Ralt RH6/84 Hondas in the series’ final year, F2 cars never looked anything other than stunning, as page after page (after page!) of imagery reminds us.

Thanks to British journalist Marcus Pye, each seasonal summary is illustrated with period racing stickers. Stickers were virtual currency for young race fans as well as (sometimes literally) a “get out of jail free” card at tricky border crossings. Some related to the race car marque itself, and may I confess an enduring love of the crocodilian Tecno badge? Others are reminders of sponsors whose logos adorned sidepods and wings from Finland to Sicily. I may never have owned(or smoked) anything branded Matchbox, Bang & Olufsen, Scaini, Bastos, Colibri, or Everest but I still know what the products are, and I enjoyed spotting them in Jutta Kausel’s photographs of race cars from Surtees, Boxer, and March.

If this is not the book I had expected, it is still welcome, because F1 monopolizes motorsport coverage almost to the exclusion of all else. Formula 2–The Glory Years is a long way from being the final word on Formula 2, as that book has yet to be written. But despite my caveats, I guarantee that if you immerse yourself in the wealth of imagery in this book, you will be transported back to an era which truly was golden.

If this is not the book I had expected, it is still welcome, because F1 monopolizes motorsport coverage almost to the exclusion of all else. Formula 2–The Glory Years is a long way from being the final word on Formula 2, as that book has yet to be written. But despite my caveats, I guarantee that if you immerse yourself in the wealth of imagery in this book, you will be transported back to an era which truly was golden.

I first saw F2 on a cold and grey March day at Mallory Park in 1971, and it was the first international single-seater race I’d ever seen. I’d nearly crashed my dad’s Triumph Vitesse en route while showing off my driving skills. But five minutes spent watching F2 cars braking from huge speed, then jinking and sliding through Shaws Hairpin was enough to convince me that the only time I’d be behind the wheel of Lotus 69 was in my dreams.

Copyright John Aston, 2025 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter