Sports Car Racing in the South: Texas to Florida, 1961–1962

by Willem Oosthoek with Photography by Bob Jackson

“The national press of the period often ignored Southern events. Even the Sports Car Club of America, the primary sanctioning body for amateur road racing, fell short and reported on few Southern races in Sports Car, its own monthly magazine. Today, the SCCA archives of what can be considered the Golden Age of sports car competition are non-existent. As a result the subject has become a virtual black hole in the history of motor racing.”

It is said that all good things must come to an end (and come in threes), which means that we should truly appreciate this third and latest volume of Oosthoek’s Sports Car Racing in the South: Texas to Florida, which covers the years 1961 and 1962. The trilogy represents a Herculean feat of research, and that the subject matter falls well outside the usual scope of topics under the heading of automotive competition history makes the effort all the more laudable. However, even as dogged a researcher as Oosthoek now says in the Preface that there are finite limits to what can be sifted and sorted from what is a very diminished archival database.

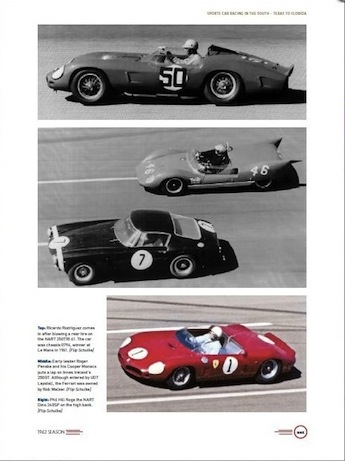

All the remarks about design, concept, and methodology we made regarding vols 1 and 2 apply here the same. Volume three begins with a recap of the 1959 and 1960 season that were covered in the second volume, adding additional information and photos that surfaced after that volume was printed. Many of the photographs are fascinating in and of themselves, such as that of the Lance Reventlow/Ed Martin Ferrari 250TR with its damaged front fender from the 1959 Sebring 12 Hour race: it is the sort of photo that does not usually find its way into race reports.

All the remarks about design, concept, and methodology we made regarding vols 1 and 2 apply here the same. Volume three begins with a recap of the 1959 and 1960 season that were covered in the second volume, adding additional information and photos that surfaced after that volume was printed. Many of the photographs are fascinating in and of themselves, such as that of the Lance Reventlow/Ed Martin Ferrari 250TR with its damaged front fender from the 1959 Sebring 12 Hour race: it is the sort of photo that does not usually find its way into race reports.

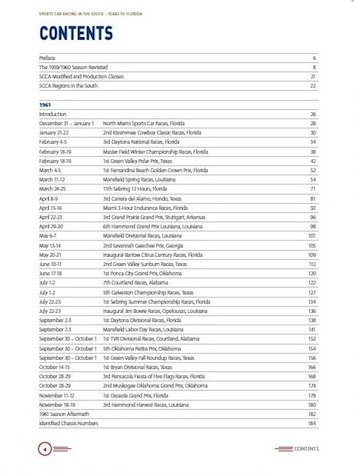

The format of the third volume mirrors that of the previous two: Each season is given an introduction which provides it with a context for the events within the region; each event is given some measure of coverage, the details of the meeting being given, often with a layout of the racing circuit, along with any photographs of the event. As with the previous volumes, the Sebring 12 Hour races of 1961 and 1962 are given space.

The photographs are again both interesting and well selected, and the reproduction is excellent. One of the many that catches the eye is that of the Jaguar C Type with a Chevrolet engine on p. 81 taken by Bob Jackson at the race meeting in Hondo, Texas in April 1961: the paint job is simply amazing! Another Jackson photograph, this one from the Galveston race in July 1961, shows not only the engine of the Jim Hall Chaparral but provides a good view of the Goodyear tires being used (pp. 131/2). To see Joe Weatherly driving by in a Lister in the background of a photo featuring Dan Gurney and the Arciero Brothers Lotus 19 (pp. 196/7) and then see him getting to ready to participate in a Le Mans start at the Daytona 3 Hour Continental event in February 1962 are reminders of just what a different age it was over a half century ago.

The photographs are again both interesting and well selected, and the reproduction is excellent. One of the many that catches the eye is that of the Jaguar C Type with a Chevrolet engine on p. 81 taken by Bob Jackson at the race meeting in Hondo, Texas in April 1961: the paint job is simply amazing! Another Jackson photograph, this one from the Galveston race in July 1961, shows not only the engine of the Jim Hall Chaparral but provides a good view of the Goodyear tires being used (pp. 131/2). To see Joe Weatherly driving by in a Lister in the background of a photo featuring Dan Gurney and the Arciero Brothers Lotus 19 (pp. 196/7) and then see him getting to ready to participate in a Le Mans start at the Daytona 3 Hour Continental event in February 1962 are reminders of just what a different age it was over a half century ago.

In 1962, the United States Auto Club held an event in its Road Racing Championship series at the Hilltop Raceway, located near Bossier City, Louisiana. At the time, what coverage the race received was, to be kind, scant to little, even though it had Dan Gurney, Roger Penske, Lloyd Ruby, and Jim Hall in the field. Oosthoek provides what is probably the only real coverage that long-neglected event has ever received (pp. 236–249). The photos of Bob Schroeder in the de Tomaso Isis entered by John Mecom are more than likely the first many will have ever seen of this machine in action. Until such time that someone finally does an in-depth monograph on the USAC Road Racing Championship, this is likely the best coverage this event has gotten yet.

To demonstrate the level of effort that went into this volume, Oosthoek includes a 4 hour race that took place in Columbia, South Carolina, in June 1962. That he managed to unearth this event is amazing—I was there and even I had almost forgotten it! This was an endurance race held on the local sports car club’s property across from the Columbia Airport and I spent most of the race in the pit of Graham “Tombstone” Shaw, but I wouldn’t have known today the year the event took place or what car Graham drove—until I came across the report in the book.

To demonstrate the level of effort that went into this volume, Oosthoek includes a 4 hour race that took place in Columbia, South Carolina, in June 1962. That he managed to unearth this event is amazing—I was there and even I had almost forgotten it! This was an endurance race held on the local sports car club’s property across from the Columbia Airport and I spent most of the race in the pit of Graham “Tombstone” Shaw, but I wouldn’t have known today the year the event took place or what car Graham drove—until I came across the report in the book.

One could go on and on and on praising this book—and the previous two volumes (Vol. I won the SAH’s 2012 Cugnot Award). As wonderful as the photos are, the narratives and captions written by Oosthoek are essential to the quality of this work. As a retired banker and world-renowned historian and activist in the Maserati world Oosthoek is no stranger to the rigors of research and the pursuit of accuracy and micro detail. Even so, the obstacles to doing this sort of work and at this level cannot be overstated. Massive amounts of data need to be churned and vetted, assuming any is found in the first place. Long overlooked, the topic of racing in the South seems peripheral only to those who have never been given a cohesive view of it. These books do that, which makes it all the more bittersweet that this installment may be the last one. (The original plan called for it to end in 1963 not 1962.) If so, the series is ending on a high note!

This excellent book cannot be recommended highly enough. Limited to 600 numbered and autographed copies.

Copyright 2015, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

It’s a shame that the book ends with the ’62 season. The 1963 12 Hours of Sebring was epic, with the incredible field of Cobras and privately entered GTOs, and the internecine battle inside the Ferrari team, with Surtees and Dragoni practically in open warfare.