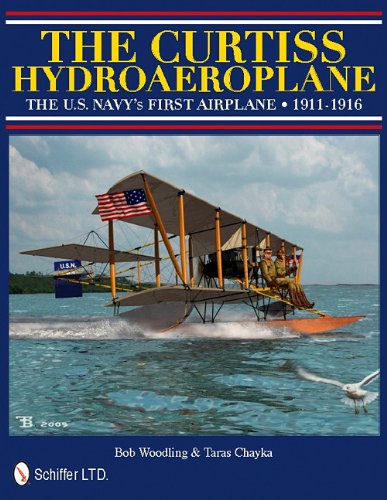

The Curtiss Hydroaeroplane: The U.S. Navy’s First Airplane 1911–1916

by Bob Woodling and Taras Chayka

by Bob Woodling and Taras Chayka

“The Navy’s first airplane was in some ways the product of seemingly unconnected personalities of vastly different interests and social status. That those people ever became connected appears to be a miracle of sorts.”

Published in the centenary year of US Naval Aviation, 2011, it is only fitting—and long overdue—that there should be a properly thorough book about the Navy’s first aircraft.

The history of early aviation in the US is dominated by the Wright Brothers, who had demonstrated their machine to the Army and Navy in 1908, but they were of course not alone. It must be realized that in those pioneering days there was no such thing as a syllabus of “aeronautical engineering” or a large body of theoretical knowledge, nor even a “fraternity” among those pursuing similar goals. Anyone, in fact, approaching this book from a Wright-centric point of view may be puzzled to note that they are mentioned all of two times in the entire book—but it is exactly the fact that the Wright way was not the right way of doing business, or, specifically, establishing rapport with the military.

The book begins with a look at why and how balloons and kites were made steerable, which required propulsion, which required a lightweight and reliable engine, which is how one Glenn Curtiss (b. 1878), successful racer and builder of his own motor-bicycles, comes to the attention of the flyers—culminating in the foundation in 1907 of the Aerial Experiment Association. (This is also the year in which Curtiss garnered the title “Fastest Man on Earth” for his motorcycle exploits; this and other Curtiss activities are of course mentioned here but, being peripheral to the book’s purpose, only in passing and not in a way that makes clear how many things he had going on concurrently.) All this should be of interest to anyone dealing with the history of ideas in general, especially considering that the AEA and the brothers Wright ended up in years-long litigation over alleged patent infringements. This episode is, alas, dispensed with here in one single sentence and the novice reader asking the obvious questions (why didn’t the Navy order a Wright aircraft, what did the Wrights think of all this) will be left to read between the lines.

Technical matters are discussed in good detail, conveying well the challenges in operating a flying machine from the sea: lift and drag in the air and in the water, the suction forces of early seaplane floats, power limitations of the early engines. Issues such as supply and logistics for water-based aircraft are touched upon only in passing, as is the matter of navigation.

All aspects of defining the operational parameters and the design, construction, and testing of various models are well covered, as is their use by foreign navies. Most remarkably, several years of examining the one original survivor and several museum replicas (airworthy and static displays, each discussed in a closing chapter) have yielded some 25 pages of detailed technical drawings of the 1912 “E” model in 1:6, 1:12, and 1:36 scale. Color profiles and 3 top views show several versions in different US, Russian, and Japanese markings.

An extensive Bibliography and a Name Index round out the book, which, as pretty much all offerings by this publisher, is profusely illustrated, printed on excellent paper, nicely bound, and has those lovely old-timey marbled endpapers.

Copyright 2015, Charly Baumann (speedreaders.info).

The Curtiss Hydroaeroplane:

The U.S. Navy’s First Airplane 1911–1916

by Bob Woodling and Taras Chayka

Schiffer Publishing, 2011

256 pages, 150+ color/bw images, hardcover

List Price: $59.99

ISBN-13: 978-0764337628

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter