Clydebank Battlecruisers: Forgotten Photographs From John Brown’s Shipyard

Battlecruiser! To the knowledgeable and enthusiastic, the term evokes mental images of “bone in the teeth” flank-speed bow waves and frothing wakes, funnels belching trails of position-revealing coal smoke, salvoes of big guns firing simultaneously with their attendant clouds of impenetrable gunpowder smoke, splashes from the near misses of armor-piercing shells rising higher than the mastheads of the ships they were aimed at, and in a few spectacular cases, devastating main-battery magazine explosions that sent these magnificent leviathans to the bottom of the sea in a matter of minutes, taking their crews with them. “Eggshells armed with hammers” their critics described them, yet the major navies of the early twentieth century enthusiastically embraced their concept, then designed and built them as fast as they could. The first was laid down in 1905 and the last in 1916, a timespan of a bit more than a decade that ended a century ago. Historians of that epoch leading up to the tragedy of the First World War remain fascinated with them and their influence on the belligerent navies’ war-fighting policies before, during, and even after that cataclysmic event. Twenty-four were completed and commissioned; thirteen by the British Royal Navy, seven by the Imperial German Navy, and four by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Ironically, the keel of the last one to be completed, the ultimately ill-fated HMS Hood, was laid the same day the type achieved its greatest notoriety and controversy at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 when three of them, all British, blew up in combat action. Many more were planned and indeed started, but Hood would be the very last one completed and officially cataloged as a battlecruiser, and that not until 1920.

The battlecruiser was considered at the time to be the logical next step after the armored cruiser in warship development. The armored cruiser was second only to the battleship in status at the turn of the twentieth century. It was intended to carry out reconnaissance in force for the main battle fleet as well as independent operations in defense of trade routes, capable of defeating the lesser warships typically assigned the role of commerce interdiction, yet fast enough to decline combat with more powerful adversaries. Their main armament was typically the equivalent of (or slightly more powerful than) a contemporary pre-Dreadnaught battleship’s secondary battery armament. This standard originated in Britain’s Royal Navy and was more or less universally observed by all others. Indeed, it was the Royal Navy’s Admiral Jackie Fisher who is credited with turning the concept of an armored cruiser hull armed with battleship main battery guns—the definition of the battlecruiser—into reality. The concurrent development of the marine steam turbine, which allowed for reliable sustained high-speed operation completed the recipe for the ideal warship that could “outrun anything it couldn’t outfight.” Yet by the outbreak of war in August 1914, warship technology had progressed so rapidly that the concept of the fast battleship was being seriously discussed and considered not far from reality. It was this development, as well as that of the aircraft carrier (which ultimately assumed the battlecruiser’s scouting role) that led to the type’s rapid obsolescence.

The topic is one that has been well explored in the literature. A great many books have been published about battleships and battlecruisers over the past several decades. Most are illustrated with historical photographs and finely drafted line drawings to augment their texts. A good number of the photographs appear repeatedly in many of these books, leading one to believe there is a dearth of surviving photos available to researchers and authors. This exceptional book proves otherwise. Though the photographic records of many of the builders of battleships and battlecruisers have not survived, if indeed comprehensive photographic archives existed at all, those of John Brown’s Shipyard on the River Clyde, downstream from Glasgow, Scotland have. Unlike other shipbuilders, John Brown’s established its own professional photo department to document the progress of construction of virtually all the ships the yard constructed, be they large or small, merchantman or warship. Even more importantly, those photographs have survived decades of storage, war, and ultimately the liquidation of the company. Instead of being carelessly discarded when the company wound down its operations, as has so often been the unfortunate case, the shipyard’s archives were donated to the Glasgow University Archives. The photographers who made these photos used large format (10″ x 12″ and larger) cameras and glass plate negatives to produce exceptionally sharp images of the finest details; the state of the art at the time. Because they used glass plates instead of flexible film that becomes brittle and disintegrates with age, the negatives, if stored properly, will last indefinitely. The century-old photos used in this book prove that beyond question.

John Brown’s built five of the Royal Navy’s thirteen battlecruisers: Inflexible, Australia, Tiger, Repulse, and Hood. Each constitutes a different class and receives its own chapter, so the entire spectrum is almost comprehensively covered. I say “almost” because purists will argue that Tiger, though constructed to a modified Lion-class design, is in fact different enough to represent a one-ship class, as it had no identical sisterships. I tend to agree with this line of thought.

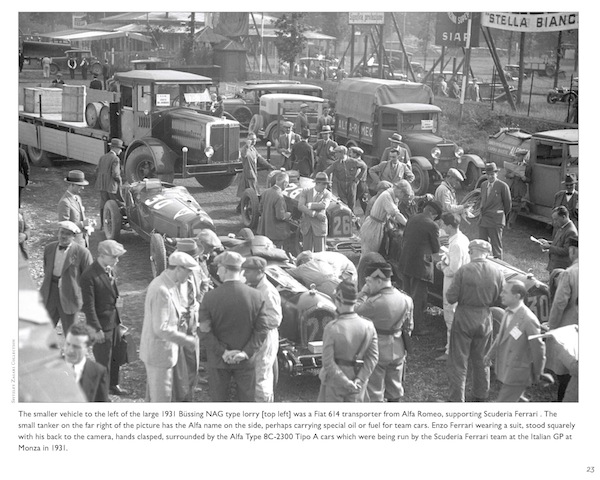

Each ship’s construction is well documented, from keel laying to fitting out and sea trials. Thanks to the employment of state of the art scanning and high resolution digital printing, the overall quality of photographic reproduction is, in a word, superb. Though large photos often run across the gutter between facing pages, this appears to have been done primarily for compositional balance and rarely obscures important details. And details abound throughout. Students of naval architecture will find clear details of features and construction techniques not visible once the ship is complete. Modelers will find these photos of the ships “as built” to be invaluable references. Though the vast majority of the photos appear to be somewhat dark and drab in tone, they are an accurate reflection of the climate, where overcast conditions are far more prevalent than clear, sunny skies. This is actually an advantage in photography, as the harsh shadows that come with sunny skies often completely obscure important details.

Photographs and their captions, which are neither too short nor too long, are the heart and soul of the book. Overall, the text is noteworthy for its comprehensiveness, detail, and readability. Statistical details are frequently presented, but care has been taken to explain them in the context of the times in the accompanying text, instead of the simple, dry tabular display so often found in historical works. The photos themselves are of great variety, though some views of each ship are compositionally similar. While seemingly redundant, those photos were included deliberately so as to provide a sense of scale that would otherwise be difficult to convey. Physical dimensions of 9.5″ x 11″ are just right for impressive photographic display. White space around photos is admirably minimal. The Index is limited to one page, but that is one page better than nothing.

It is a shame that more photographic archives of this nature have not survived, but we can take heart that this one has and that Ian Johnston has done such a laudatory job in bringing them to light in a manner that allows for frequent and easy reference. If you are a serious student of this subject and era, this landmark book and its by now several companions are indispensable.

Copyright 2016, Mark Dwyer (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter