The Perfect Car

The Biography of John Barnard, Motorsport’s Most Creative Designer

John Barnard is one of the few designers of Formula 1 cars who deserves to be included in the same sentence as Colin Chapman, Gordon Murray, and Adrian Newey.

The latter’s defining mantra, “How can I do this better?” could also be the credo which drove Barnard to such obsessive lengths in his career but I would suggest that any resemblance between the two would end there. Because, on the evidence of The Perfect Car, Barnard was an extremely difficult man with whom to have had a professional relationship. He fell out with McLaren’s Teddy Mayer and Ron Dennis, Chaparral’s Jim Hall, Tom Walkinshaw (Arrows etc.), Benetton’s Flavio Briatore, and just about everybody who worked for Ferrari. Barnard was confrontational, lacked empathy, appeared emotionally stunted, had little time or respect for many of his peers, and had a temper with the shortest of fuses. But he was also responsible for some of the most important innovations in modern motorsport and, if imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then the man some called the Prince of Darkness also had many admirers.

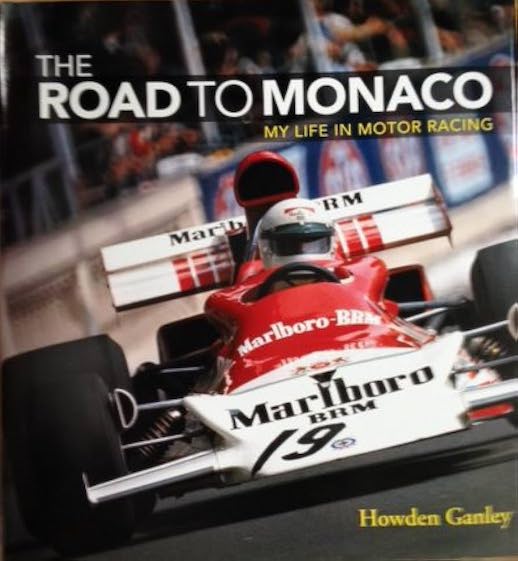

Barnard created the first carbon fiber monocoque, pioneered on the 1981 McLaren MP4, the paddle shift gearbox which first appeared on the 1989 Ferrari 640, and the multifunction steering wheel introduced on the Ferrari 647 in 1996. And those are just the best-known highlights. There’s along list to choose from and, unlike most innovations in Formula 1, two of Barnard’s are now found in an increasing number of normal road cars, as well as in the majority of upmarket sports cars. They are, of course, the paddle shift and the steering wheel control buttons. Appropriately enough, I can think of very few, if any, road cars whose steering wheels have such a superfluity of buttons and knobs as the current Ferrari 488GTB.

This is a big book of almost 600 pages, sumptuously printed on satisfyingly thick paper between faux carbon fiber cover boards. The typical online price of $53 reflects its quality. Freelance journalist Nick Skeens has produced a beautifully written and comprehensive biography and, although he does not come from a motor port background, the depth and clarity of his technical explanations are exemplary.

If I have a criticism it is that, at times, it feels as though the author has been blinded by the light of Barnard’s talents; even the book’s subtitle Motorsport’s Most Creative Designer is controversial at best and plain wrong at worst. There is sometimes an element of hagiography in this book and, whilst it certainly does not spoil the work, it did sometimes provoke the odd curse from this reader. Perhaps the best example of the stars in the author’s eyes is found in his account of the genesis of the carbon fiber MP4: “Barnard’s genius had inspired him not only to adopt cutting edge technology, master it and introduce it to motorsport but to actually push forward the work of rocket scientists. . . .” Which may be true in part but it glosses over the fact that carbon fiber was already in widespread use in other applications by 1981. Carbon fiber fishing rods and golf club shafts had been on sale for over a decade before the MP4 appeared. Further, Brabham’s Gordon Murray had also used the material, if not as extensively as Barnard did. Barnard deserves every credit for being the first to design a fully carbon fiber-bodied Grand Prix car but, even in 1980, the question was not if such a car would ever be made, but when.

This cavil apart, it is a fascinating book and, perhaps ironically in a book about Barnard, it is the human element which makes it so difficult to put down. There was no silver spoon in Barnard’s mouth as he came from a working class family in North London and, unlike most of his contemporaries, he did not go to university. But even as a teenager he had demonstrated an extraordinary ability to improve, design, and construct anything he turned his hand to. In 1965 not many British teenagers owned a car of any description, and, if they did, it was likely to be a wheezing old Mini or Austin A35. Not Barnard though, as he bought an Aston Martin DB2/4 with his own money and, after the original straight six had expired, he installed a 4.7L Chevy V8 and entirely by himself. As Skeens puts it, “this would have been to break a purist’s rules but he was young and raring to go.”

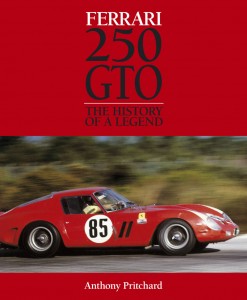

Even at such a young age, Barnard was already showing the same confidence, impatience, and unshakeable self-belief that would characterize his later career. Those were the same traits, however, that would trigger Barnard’s rages at any mistakes his father made when helping his teenage son with his projects. And, much later, those traits were ruthlessly brought to bear on anybody with whom Barnard disagreed, regardless of their status or reputation. Yet Barnard is far from the single-dimensional tyrant his critics and rivals might suggest—Skeens also describes a man so devoted to his family that he agreed to work for Ferrari on condition that he could remain in Surrey at his Guildford Technical Office, which was conveniently and appropriately abbreviated GTO. For most of his career Barnard made a point of going home from work every day to join his family for lunch. Which I thought was a bit rich, as John Barnard, notoriously, was also the man who put a stop to the long standing tradition of Ferrari mechanics having a sit-down pasta and Lambrusco lunch. . . .

Skeens has really done his homework in researching the book and I found the details of Barnard’s early career in motorsport fascinating. I enjoyed the insight into Barnard’s relationship with the patrician Patrick Head at Lolaand, despite their very different backgrounds, Barnard became a lifelong friend of Williams’ future engineering director. There are tales of Barnard’s time with lesser known figures too, such as the near legendary Ronnie Grant who, in his Barnard-designed Taurus, was a frontrunner in Formula Super Vee in the early 1970s. Grant was the ducking and diving cockney geezer who later went on to race against drivers such as Martin Brundle and Ayrton Senna in British Formula 3, albeit without quite the success he had enjoyed in lower formulae. Head and Barnard termed Grant’s “under the arches” London garage “The Black Hole of Calcutta” with Head recalling that it was populated by “cab drivers with wonderful names like Cold Hands, Rucker Renton, and Jake the Bake.”

Barnard might be best known as the uncompromising pragmatist but, as Skeens recounts, he did have some curiously endearing character traits, none more so than his affinity for certain numbers. And that is why, in 1979, Al Unser’s 202.202 mph qualifying lap at Ontario Motor Speedway in the Chaparral 2K so resonated with him. “There are certain numbers I always like: 202 is one, 2 and 4 are others . . . If I can design using nice round numbers without any cost to performance I will; I’m always going to prefer 176 to 176.395.” There’s an interesting contrast to Gordon Murray’s approach, which is similarly idiosyncratic, as he once told me “where there is a piece of the car that wasn’t specifically for aero reasons I just made them look good . . . I love styling.”

The friend who recommended this book to me said the Ferrari element of the Barnard story resembled a Greek Tragedy, and I cannot disagree. And yet it is even more than that, as Maranelloin the late 1980s was also a bearpit of Machivellian intrigue, backstabbing, and paranoia. But even in the almost sacred environment of Ferrari, Barnard absolutely refused to be cowed by anyone; he once described his predecessor Harvey Postlethwaite as “incompetent.” He even persuaded Enzo Ferrari to sack Piero Lardi Ferrari, his illegitimate and only surviving son, for having authorized a rival Formula 1 car to be designed in-house because Barnard’s own design was considered to be almost dangerously innovative.

But even the Ferrari soap opera was shaded by Barnard’s tempestuous relationship with the man who some called “Ronzo”—Ron Dennis. The book’s most extraordinary passages come at its end, when the author accompanied Barnard to the McLaren Technical Centre in late 2014 to meet Barnard’s former partner, boss, and rival. Skeens writes about the clinical, money-no-object extravagance of the Centre beautifully, quoting Dennis’ description of the ludicrously named McLaren Thought Leadership Centre as a “total immersive experience.” I just bet it is. . . . The account of the two old warhorses trading verbal punches, with Dennis boasting and obfuscating in trademark “Ronspeak” and Barnard probing and provoking in return, makes for riveting reading. And it is made even more so by the reek of hubris, as Ron Dennis was to be sacked from his life’s work, McLaren, less than two years later.

As mentioned above, I interviewed Gordon Murray a few years ago, and it was both a delight and an education to do so as, I suspect, it would also have been if Adrian Newey had been the subject. But I am not sure that a conversation with John Barnard would be quite as straightforward, as the man who has been “possessed by a fury with imperfection” since childhood is perhaps unlikely to be easy company, certainly not on the evidence of this book. But that doesn’t matter a jot, as one of his creations can say more about John Barnard than the man himself ever could, or would. The object in question is the only car ever to be permanently exhibited in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the achingly lovely and perfectly proportioned Ferrari 641, the car that contested the 1990 World Championship in Prost’s and Mansell’s hands. A Barnard car in all but name, an evolution of the game-changing 640 and, despite competing claims from the Lotus 25 and the Eagle Weslake is, I think, the most beautiful rear-engined Grand Prix car of them all. Barnard doesn’t need words, not when his deeds can look this good.

Copyright 2019, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I learned a lot from this book, not just about Barnard, but also about Jim Hall, Piero Lardi Ferrari, Harvey Postelthwaite and others….and I haven’t even read the Benetton chapter yet!