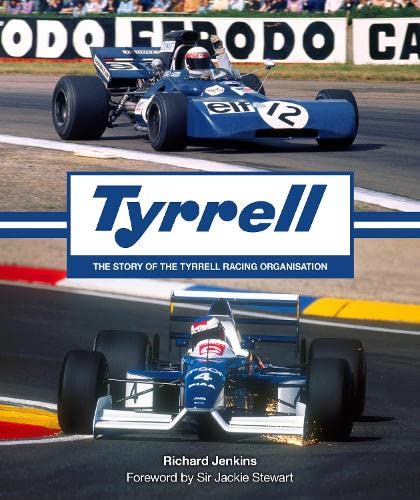

Tyrrell: The Story of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation

by Richard Jenkins

by Richard Jenkins

“He always dissipated my tension. Ken was a great father-like figure to me. The way he helped the driver was not like a team manager or businessman, it was like a father.”

—Jean Alesi, Tyrrell driver 1989/90

April 9, 1971 was an unforgettable Good Friday for me, because it was the day when I saw my first Formula One race. The Daily Express Spring Trophy was held at Oulton Park and the first car I saw was Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell 001, sideways on cold tires at Lodge Corner. The image of that stubby dark blue car, the driver’s busy hands, and the tartan-trimmed white helmet has never left me. Richard Jenkins has already written two well-received biographies, of Richie Ginther and Mike Spence, but they were relatively marginal figures and of real interest only to the serious student of 1960s’ motorsport. But Ken Tyrrell (1924–2001) was not marginal, he was one of the handful of team owners who dominated Grand Prix racing in the late Sixties and early Seventies, and I was intrigued to see how the author would rise to the challenge.

I have good news—Richard Jenkins has written a wonderful biography of Ken Tyrrell the man, and his eponymous race team. I did feel that Jenkins’ earlier books were sometimes hard work for the casual reader, and it didn’t help that the text would sometimes go down rabbit holes of decreasing relevance to the subject. That criticism, such as it is, doesn’t apply here, and the 480-page, large-format hardback from Evro does full justice to that quintessential Englishman, Ken “Chopper” Tyrrell. He was the honorable, tough, and decent man who achieved huge success, surviving twenty years of Formula One’s “Piranha Club” before being betrayed by his erstwhile friend Bernie Ecclestone and effectively forced to sell his team to a pair of deluded chancers and Adrian Reynard.

A huge amount of research has gone into the book, as witness the fact that Jenkins has spoken to 30 of the 38 surviving Tyrrell drivers, scores of other members of the team, and also to family members. The detail never overwhelms, but there’s no hiding place from the author’s diligence, which means a wealth of extracts from contemporary sources such as Autosport, Sport Auto and Motor Sport magazines, as well as newspaper extracts from The Scotsman and Evening Standard, inter alia. The author emphasizes that “it was important not to get too bogged down in race summaries and results,” an objective he achieves—just. But races like the 1968 German Grand Prix merit more than passing mention. If you need reminding, this was the race won by Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell-run Matra MS 10 by a four-minute margin.

Jackie Stewart (who wrote the Foreword to this book), described by Tyrrell early in their relationship as “someone who pranced around and made a general nuisance of himself,” is the fulcrum upon which the early Tyrrell story balanced. He may have won his three world championships for the team but his afterlife as a retired race driver (fifty years and counting), “brand ambassador,” and elder statesman overshadows his achievements for Tyrrell, and those of the team itself. We have perhaps grown too accustomed to Sir Jackie’s tartan-trousered figure on F1 television coverage, and we’ve heard his well-honed anecdotes so often that we risk forgetting what a scintillatingly brilliant driver he was. And we may have also forgotten how bravely he fought his safety campaign (with Tyrrell’s support) against a motor racing establishment that regarded death and injury as collateral damage. Stewart’s only “sin” is to have survived—how much more would he now be venerated if had he died in a race car, like his friends Jim Clark and Jochen Rindt? Wasn’t that fate almost inevitable then, the exit in a blaze of glory and another name immortalized?

But the Tyrrell story is about so much more than Stewart, whose immediate retirement after Francois Cevert’s fatal accident at Watkins Glen is described less than a third of the way through the book. Success had come quickly to Tyrrell, with Stewart’s three world championships in the team’s first six years of Formula One, but the author’s account of the team’s next quarter century is what makes this book such a compelling read. Although the narrative comprises a season-by-season account, it is interspersed with profiles of “Tyrrell Heroes,” the key people in the Tyrrell story. Even casual students of the sport’s history (if not most Drive to Survive viewers) have heard of designers Derek Gardner, Maurice Philippe and Harvey Postlethwaite, but Keith Boshier and Roger Hill are less well known but equally important figures in the team’s history. The eccentric genius Boshier and mechanic “with the magic hands” Hill were both long-term denizens of the famous Tyrrell shed (now saved and relocated to Goodwood) and their profiles add texture and color. At heart the book is about the people without whose contributions Tyrrell would have been not only a less successful race team but a less likeable and endearing one. Eccentricity wasn’t unknown in the cockpit either, as neither Stefano Modena nor Andrea de Cesaris ever sailed too close to the conventional, and who could not love a team that even displayed whimsical pit signals? Towards the end of Stewart’s majestic drive in the 1973 Italian Grand Prix, the Scot recounts that “the team was thinking that I might get bored . . . so they started giving me pit signals like ‘45 seconds FANGIO.’” Even against competition from the Brabham BT46 B fan car, the BRM V16, and the Pratt & Whitney gas turbine-powered Lotus 56B no other F1 car ever attracted media interest like the six-wheeled Tyrrell P34 did in September 1975. “After a few seconds, journalists couldn’t get to the phones quickly enough, they were like maniacs,” long-serving team member Rollie Law recalled.

But the Tyrrell story is about so much more than Stewart, whose immediate retirement after Francois Cevert’s fatal accident at Watkins Glen is described less than a third of the way through the book. Success had come quickly to Tyrrell, with Stewart’s three world championships in the team’s first six years of Formula One, but the author’s account of the team’s next quarter century is what makes this book such a compelling read. Although the narrative comprises a season-by-season account, it is interspersed with profiles of “Tyrrell Heroes,” the key people in the Tyrrell story. Even casual students of the sport’s history (if not most Drive to Survive viewers) have heard of designers Derek Gardner, Maurice Philippe and Harvey Postlethwaite, but Keith Boshier and Roger Hill are less well known but equally important figures in the team’s history. The eccentric genius Boshier and mechanic “with the magic hands” Hill were both long-term denizens of the famous Tyrrell shed (now saved and relocated to Goodwood) and their profiles add texture and color. At heart the book is about the people without whose contributions Tyrrell would have been not only a less successful race team but a less likeable and endearing one. Eccentricity wasn’t unknown in the cockpit either, as neither Stefano Modena nor Andrea de Cesaris ever sailed too close to the conventional, and who could not love a team that even displayed whimsical pit signals? Towards the end of Stewart’s majestic drive in the 1973 Italian Grand Prix, the Scot recounts that “the team was thinking that I might get bored . . . so they started giving me pit signals like ‘45 seconds FANGIO.’” Even against competition from the Brabham BT46 B fan car, the BRM V16, and the Pratt & Whitney gas turbine-powered Lotus 56B no other F1 car ever attracted media interest like the six-wheeled Tyrrell P34 did in September 1975. “After a few seconds, journalists couldn’t get to the phones quickly enough, they were like maniacs,” long-serving team member Rollie Law recalled.

Ken Tyrrell inspired loyalty and affection in almost everyone with whom he came into contact in his forty years in motor racing. The soccer and cricket loving former small businessman was clearly a tough, caring, and resourceful boss whose style and personality were in sharp contrast to his peers such as the ducking and diving Frank Williams and the surreally confident Ron Dennis. And his ultimate nemesis, Bernie Ecclestone, the definitive biography of whom we may have to wait for a little time yet . . .

I learned a lot from this book. Did I ever know, for example, that the driver who competed in more Grands Prix for Tyrrell than anyone else wasn’t Stewart but Patrick Depailler? And had I paid sufficient attention to grasp why the lead shot saga of 1984 that resulted in disqualification was a case study in what happens when the Formula One status quo is agitated by a non-conformist like Ken Tyrrell? As Denis Jenkinson wrote, “. . . he has not kept a low profile, exactly the opposite in fact, which made him very unpopular with lots of people.” Martin Brundle, then driving for Tyrrell comments “It is laughable how we were treated.”

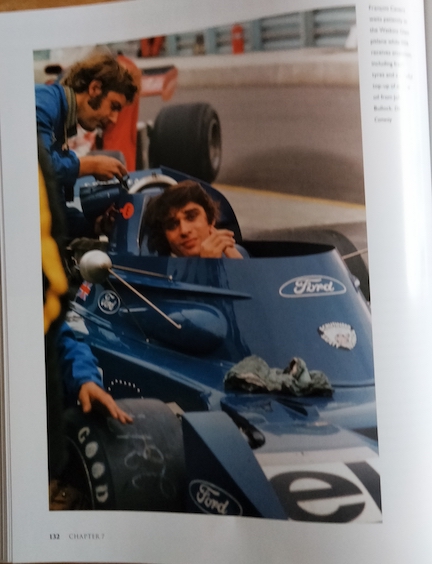

The book has a cornucopia of images, and the older they are the more interesting they become. They not only show the intended subject but are testimony to how different Formula One looked in the distant era of accessible paddocks populated by small, tight-knit teams. Each of the 23 different Tyrrell F1 cars is illustrated, but I was reminded that, with one exception, Tyrrells were defined by their functionality, with none of the catwalk queen elegance the Lotus 79, Brabham BT 52, or Ferrari 641 exuded. The exception was the 1990 Tyrrell 019, conceived by Jean-Claude Migeot and Harvey Postlethwaite. This car pioneered the “high nose” look which almost every subsequent F1 car has adopted, and which has been aped by some road cars, if only to cosmetic effect. The marriage of this car with the exuberance and brio of Jean Alesi had a compatibility perhaps unmatched since the Stewart/Cevert era.

The quotation that prefaces this review illustrates what distinguished Ken Tyrrell from most of his peers; for Frank Williams, drivers were mere employees to be plugged in and removed at whim. Not so with Tyrrell, and one of the fruits of Jenkins’ research is a wealth of evidence of the intimate, almost pastoral bond that was forged between driver and team. It might have been assumed that an old-school patriot like Tyrrell would have preferred always to employ British drivers, but that was far from the case. For every Palmer or Brundle there was an Alboreto or Streiff, a Katayama or Salo. Virtually my only criticism of the book is that I would have liked more pictures of drivers outside the race car cockpit, and I was also surprised at the virtual absence of pictures of Ken’s wife and soulmate Norah; I noticed only two.

The end of the Tyrrell team was a brutal, undignified kick in the teeth for a principled man whose outer toughness didn’t entirely disguise his inner decency and humanity. The author’s account of how the “unbelievably arrogant “British American Racing (BAR) took over Tyrrell is an almost heartbreaking read. Members of the team that had once scaled the peak of Formula One success were now being talked down to by the “pompous and patronising” Craig Pollock and his equally bullish colleagues. They also boasted, absurdly, that their new team would start winning immediately. Revenge isn’t the only dish best enjoyed cold and Bob Tyrrell confirms that plenty of Schadenfreude was enjoyed in 1999, when BAR hubristically failed to score a single point. And while Tyrrell were strangers to profligacy, I recalled the rumor of how BAR was so flush with cash that it had installed carbon fiber toilet seats in its motorhome. BAR failed, inevitably and perhaps gratifyingly, but wait, let’s consider Craig Pollock’s thoughts on his real legacy: “(Tyrrell) wasn’t great business. Just look at what we established with BAR. It’s now the Mercedes HQ.” Never mind Honda and Brawn, Toto Wolff and Lewis Hamilton—it’s Craig Pollock who deserves the credit. There aren’t the words . . .

Richard Jenkins has written an authoritative and absorbing book that belongs in your racing library. It is a moving testament to a good man whose contribution to Grand Prix racing was almost incalculable. I will finish the review with a question: Tyrrell’s contemporaries Messrs Brabham, Dennis, Head, Stewart, and Williams were honored with knighthoods for services to motorsport. But it was never “Sir Ken” and it was never even Ken Tyrrell MBE *. Why not?

Copies signed by the author available from the publisher.

- *Member of the British Empire, the lowest honor bestowed by a British monarch

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

Another Look

It has been a quarter of a century since a Tyrrell sat on the grid for the Fuji Television Japanese Grand Prix, held on 1 November 1998, on the Suzuka circuit. It was the sixteenth and final round of that that year’s world championship. In a Tyrrell 026 powered by a Ford Zetec-R V-10, Taronosuke Takagi started from the ninth row of the grid, sharing that row with the Arrows of Pedro Dinz. That seventeenth place on the grid, however, was better than four others taking the start. The other Tyrrell, that of Ricardo Rosset, failed to make the required 107% of the pole time, failing by 0.226 of a second to make the starting grid. In the race itself, Takagi retied after 27 laps thanks to a coming-together with the Minardi of Esteban Tuero.

Thus, the saga of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation came to an end.

Sort of.

On 2 December 1997, Ken Tyrrell closed a deal with British-American Racing, selling the team to a partnership headed by Craig Pollock and Adrian Reynard, both putting their own funds into the endeavor along with, of course, that of British-American Tobacco. As of the 1999 season, BAR would replace Tyrrell both on the grid and as an entrant in the Championnat du Monde des Formule Un de la FIA, the “FIA” being the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile. But, for the 1998 season it was still the Tyrrell team and Tyrrell cars, but without Ken Tyrrell. Tyrrell without being Tyrrell, if you will. In other words, while the Tyrrell Racing Organisation soldiered on into the 1998 season, in reality it was the TRO rather than BAR under a temporary guise.

Among the many items that Richard Jenkins provides us in this excellent account of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation and its founder Ken Tyrrell is something interesting regarding the registration of the current Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix Limited team from, of all places, Company House (the official government organization that keeps a record of all UK companies). When BAR bought the Tyrrell team in December 1997, it established a facility in Brackley rather than in Ockham where the Tyrrell team had its base. Today, the Mercedes team is located where the BAR team built its base. The registration number for the Mercedes team is 00787446; this is the number assigned on 9 January 1964 when the Tyrrell Racing Organisation was incorporated.

Taking a look at the bibliography Jenkins provides, it certainly seems that he did turn more than a few pages while digging into this story. It appears to be, to put it mildly, a bit eclectic in some aspects, but it certainly covers a wide range of material, with the specifics being noted. Plus, I suspect there might be even more floating around out there that helped Jenkins create the context into which he places his story.

Which brings me to this observation: Consider the sheer volume of material devoted to Ferrari and, say, Lotus, even Maserati, as compared to that for Tyrrell. Then, take Jackie Stewart out of the frame and it shrinks even more. Little wonder that Jenkins was wise to take the route of essentially creating something along the lines of, “Tyrrell: The Story of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation As Told by the Former Team Members.” Yes, there are certainly moments when one might hear a few of the lyrics from the cowboy ballad “Home On the Range” bouncing in the back of your head like an earworm: “Where Never Is Heard, A Discouraging Word . . .” That said, one does get the impression that working at TRO for Ken Tyrrell did create a sense of camaraderie and team spirit; it comes through in interview after interview. While this feeling of loyalty and, yes, devotion to Tyrrell and TRO is not necessarily all that unusual or unknown within the motorsport world, operating out of a lumberyard in Ockham, Surrey, with the Boss living in the house adjacent to the premises, created a unique sense of presence and shaped the dynamics between the members of the team and Ken Tyrrell.

Before TRO came into being in January 1964, there was the Ken Tyrrell Racing Team. Jenkins does a very good job of covering this part of the larger story, covering the Formula Junior part of the story quite well. It occurred to me that many today, even among the “Silent” and “Boomer” generations, might not remember Tyrrell’s days fielding a team during that period. That John Surtees, Ian Raby, Denny Hulme, Henry Taylor, John Love, Tony Maggs, and Tim Mayer were among his drivers might raise a few eyebrows. But, the fielding of the Mini Coopers in the touring car events at this time seems to not be of much interest to Jenkins or any of the previous biographers. Understandable, of course, so this is not a quibble but simply an observation—there is only so much one can cram into a book.

Returning to that bibliography for a moment, it took me three or fourth in-depth passes to think something was missing. I couldn’t put my finger on it but I was sure I had it on the bookshelf. It took a while to work my way to a different bookcase than the one I first had in mind and round up the relatively few books that had Tyrrell content: The Cars in Profile Collection 2 (Anthony Harding, ed., Profile Publications, 1974) containing the profile by Gérard Crombac on “The Formula 1 Matra-Fords” sat alongside Doug Nye’s The Grand Prix Tyrrells: The Jackie Stewart Cars 1970–1973 (Macmillan, 1975) and it was that arrangement that clued me in that a photo spread in Jenkin’s chapter “The Tyrrell Cars” was missing the Matra MS9, MS10, and MS80 (yes, even the MS84 . . .) and also the March 701. Oh, of course! I should have realized! I keep forgetting that Tyrrell really doesn’t exist within the realm of “Formula 1 History” until it produces the 001 in 1970. Yes, these cars are seen in their respective chapters, but leaving them out of the Tyrrell chapter is, in my mind, an interesting editorial choice.

The Matra profile by Crombac and that of the early Tyrrells by Nye certainly provide much of the nuts-and-bolts sort of stuff that keeps the techno-types quite happy (as well as those who seem to obsess over such matters even if, truthfully, they really have nary much of a clue regarding it, but one must Keep Up Appearances, as they say . . .). Sitting cheek-by-jowl with those books, as they should, I have the two posthumous volumes on Ken Tyrrell by two of the better-known scribes of the day: Maurice Hamilton’s Ken Tyrrell: The Authorised Biography (Collins Willow, 2002) and Christopher Hilton’s Ken Tyrrell: The Portrait of a Motor Racing Giant (Haynes Publishing, 2002). As Jenkins suggests, these are both quite serviceable biographies and not quite as blatantly hagiographic as so many such works tend to be. Actually, it was interesting to pull them off the shelf and re-read them in light of seeing how Jenkins approached somewhat the same topic.

All this cross-reading finally yielded an inkling as to the missing link regarding Tyrrell. Sitting together almost as if quarantined from the others (in retrospect, that was probably an intentional shelving choice on my part) are a few books focusing on the always cheerful topic of power and nastiness in the insular “fantasy world of Formula One,” especially during the Reign of the Poison Dwarf, aka a certain Bernard Charles Ecclestone—yes, an unabashedly personal opinion (come to think of it, I once had my credentials pulled from the USGP at Indy, and only after I had already arrived on scene, after one of his daughters had printed off my column for him to read, but I digress). Anyway, in my section of chronicles that deal with the underbelly of the sport were the following: Formula One: Made In Britain, The British Influence in Formula One, Clive Couldwell (Virgin Books, 2003); The Powerbrokers: The Battle for F1’s Billions, Alan Henry (Motorbooks International, 2003); Bernie’s Game: Inside the Formula One World of Bernie Ecclestone, Terry Lovell (Metro Publishing, 2003), which was later issued in paperback as Bernie Ecclestone: King of Sport (John Blake Publishing, 2009); and, Driven: The Men Who Made Formula One, Kevin Eason (Hodder & Stoughton, 2018). While Ken Tyrrell does make an appearance in the Couldwell and Eason books, almost as a cameo, Tyrrell is either almost or entirely absent from the others. This apparent lack of attention or interest is, naturally, noteworthy in and of itself.

The volume in this Rogue’s Gallery that I was searching for was—of course!—The Piranha Club: Power and Influence in Formula One, Timothy Collings (Virgin Books, 2001). I am sure that Jenkins has his reasons for not listing that book in his bibliography, but Ken Tyrrell does get time on the page in Collings’ book. Even now, over two decades later, The Piranha Club is still an interesting and informative read. Basically, only the names and teams have changed while the usual nonsense continues, mutates, morphs. Not least, you get a clear sense that the FIA and F1 are both simply Self-Licking Ice Cream Cones. Not a compliment, if you’re wondering.

As Jenkins discusses in Tyrrell, in 1984 (which at the time seems to have escaped many and only later garnered consideration) Tyrrell ran afoul of those Piranhas in one of the last acts of the nasty FIASCO War (better known as the FISA-FOCA War) that raged from about 1972 to 1984. Even lo these many years later this is still something of a touchy subject, given that, in the words of The Who, “The New Boss, Same As the Old Boss” is the only way to describe the transition from Balestre to Ecclestone (and Mosley). Ken Tyrrell, as Jenkins points out, was firmly in the No-Man’s Land of that slugfest at various moments and paid the price for it: being banished from the 1984 championship was about as forceful a lesson the powerbrokers could teach a Ken Tyrrell and any of the other minnows that might have “independent thoughts.” While TRO did have a few moments in the limelight after this, they were very few. In retrospect, the victories are even more amazing than they appeared at the time.

There were/are those, me among them, who hold that the “decision” to banish Tyrrell from the championship meant that whatever scales were left to fall from one’s eyes regarding the “F1 World” had to fall hard. The ouster of the likes of Tyrrell, who left the grid altogether in 1998 after trying to hold it together after 1984, makes the organizers’ claim of offering “brilliance” and “excitement” a hollow one, and the sport is the poorer for it.

I have long admired the work of Richard Jenkins; this book simply increases that high regard. I think that by deciding to provide us with the “story” of the TRO, rather a “history” of the subject, Jenkins made a wise move. The many interviews, the pleasant choice to treat seasons as a whole rather than the usual often tedious race-by-race-by-race, blow-by-blow accounts, and not blinking, whitewashing or candy-coating his narrative, elevate the book.

Sometimes a really good story is just that, A Really Good Story. And, fortunately, there are times when A Really Good Story That Is Well-Told delivers sound and solid history. This is one of them. I am quite delighted to have Tyrrell: The Story of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation on the bookshelf.

Thank you, Richard. Thank you.

Copyright 2023, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I’m enjoying this Another Look feature.