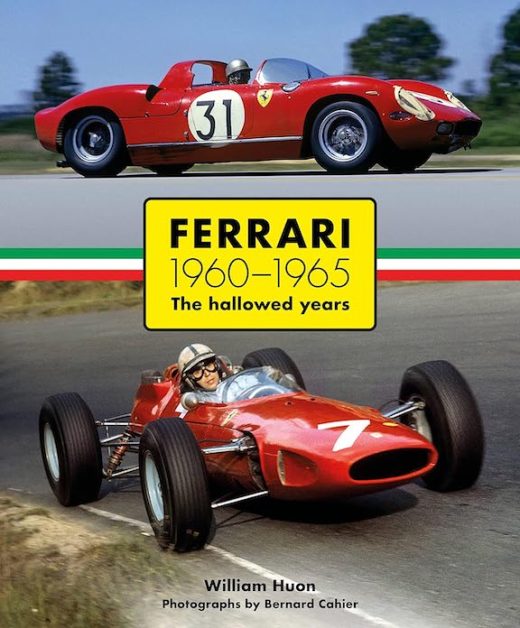

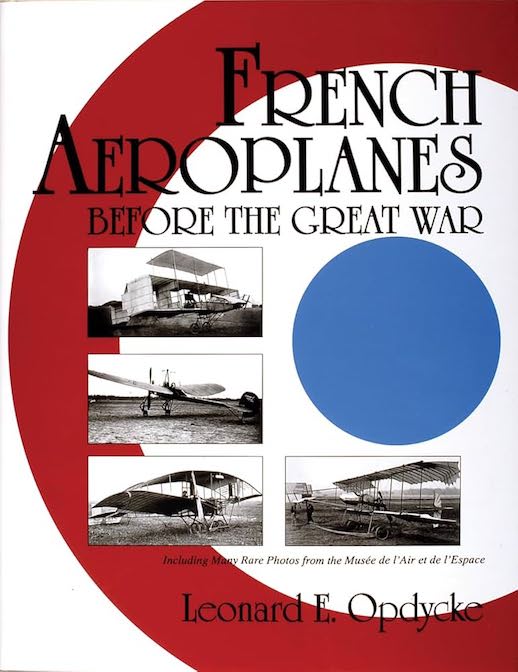

Ferrari 1960–1965: The Hallowed Years

by William Huon

by William Huon

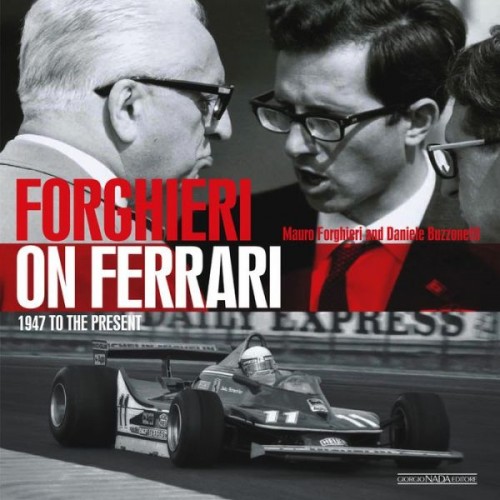

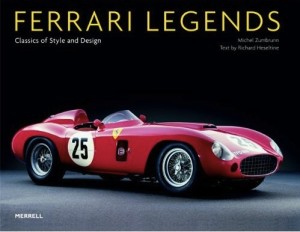

“Yet another book on Ferrari, I hear you sigh, and probably with good reason as those who write about Maranello—the man himself, his cars, his successes, his setbacks—are legion. However, I should like you to indulge me.”

It’s your loss if you don’t indulge!

A book written by an eyewitness to the proceedings, who cared about what he saw, and then cared enough to immerse himself into the bigger picture of motorsports context, and then cared even more to shoulder the burden of writing a proper book about it, well, that’s pretty much a home run. Then add period photos by a legendary photographer and you have a book that hardly needs to justify its existence.

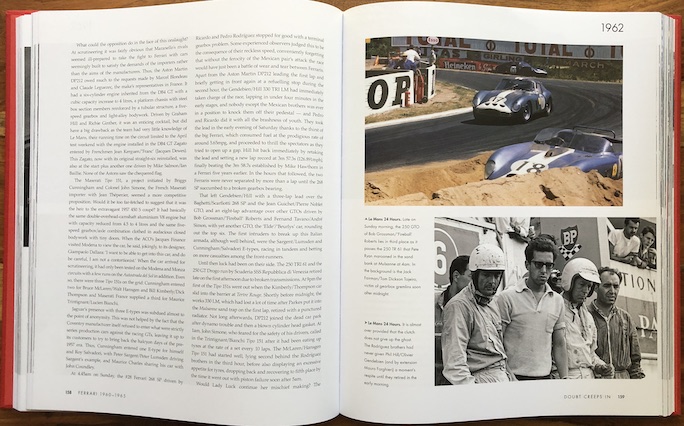

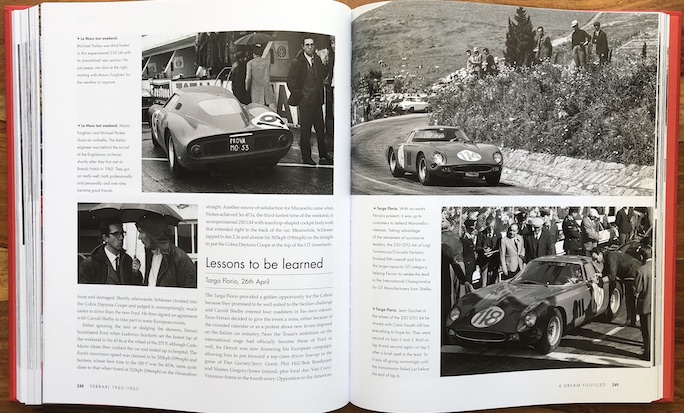

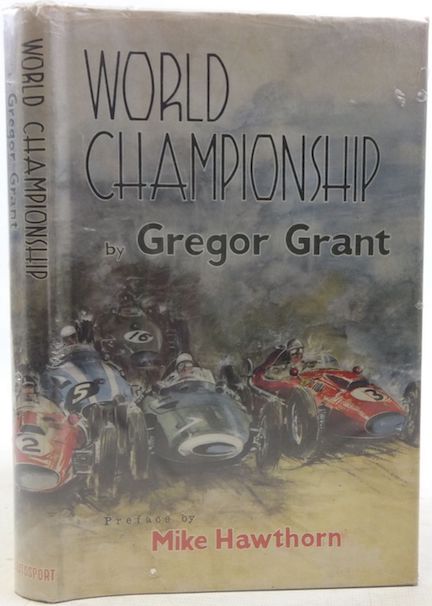

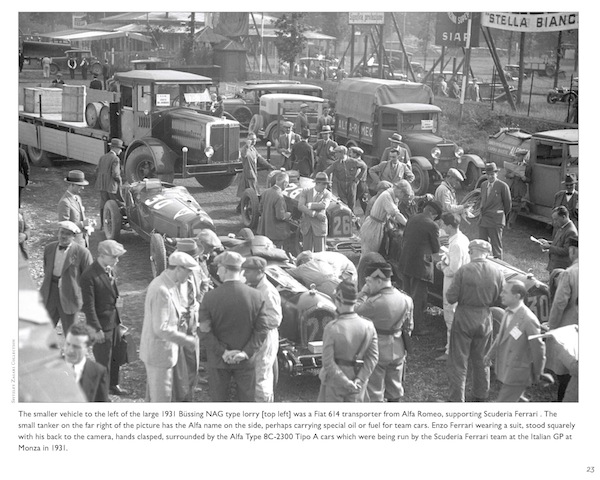

Two examples of being in the right place at the right time. Big stories behind both.

The period being examined here saw drastic changes to the sporting regulations in both formula and sports car/GT racing, and the book begins with a quick dip into the immediate backstory of the new rules announced at the end of 1958, and the ensuing acrimony among the various constructors. This aspect of the sport is always good for drama but back then there was much less of a level playing field in regards to funding and access to R&D etc. Ferrari, it must be remembered, was not then the deep-pocketed powerhouse it would become. For the sake of context, it can’t hurt to re-watch the movies Ford v Ferrari (2019, more for the personality angles than anything) or Grand Prix (which was shot right about that time, 1966, so it gives an authentic impression of what formula racing looked and felt like) to warm up.

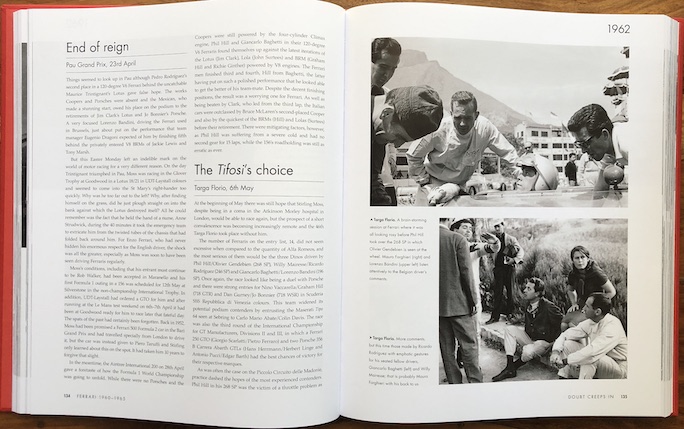

An example of the type of results table. More importantly a fine photo of an exhausted 18-year-old Ricardo Rodriguez. It breaks your heart—two years later the talented driver will be dead.

The book is divided into 6 acts and the Table of Contents tells the whole story right in the chapter titles: 1960, The Turnaround -> 1961, Triumph and Tragedy -> 1962, Doubt Creeps In -> 1963, The Messiah Arrives -> 1964, A Dream Fulfilled -> 1965, Running Out of Steam. These titles are a little bit for effect but they’re clever nonetheless. The key thing to emphasize here is that while the focus is on Ferrari, the wider story of the sport—people, tech, rules, competitors etc.—is always present.

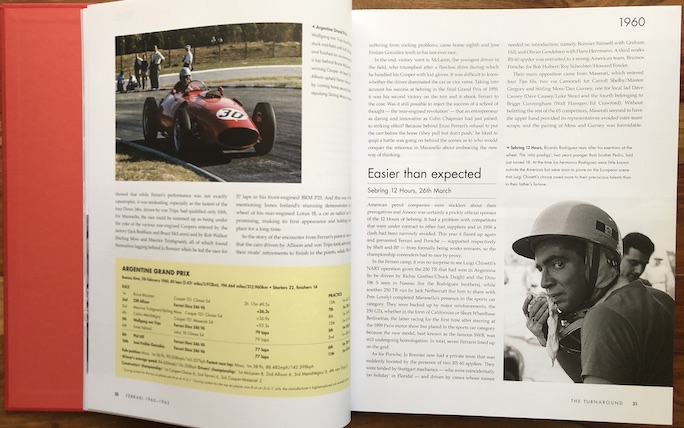

If it weren’t for the caption you wouldn’t know the shot on the left is of the podium, with Laura Ferrari horning in “seeking to share the limelight.”

Neither Huon nor his English translator David Waldron (the book was originally published in French as Ferrari 1960–1965, le temps des sacres, by ETAI) are newcomers to the subject matter. Waldron, who has lived in France most of his life, has been a 24 Hours of Le Mans trackside commentator since 1988. As a translator he must obviously stay faithful to the source material so it is a happy marriage that Huon on his own has a rather reporterly, crisp, on-message writing style. Moreover, one of Huon’s Ferrari books is a biography of Enzo F. (Enzo Ferrari – une vie pour la course) which lends weight to his analyses of, say, Enzo’s continued waffling about designating a lead driver, or wife Laura’s meddling, both issues that did incalculable damage to morale within the team/s and at the factory.

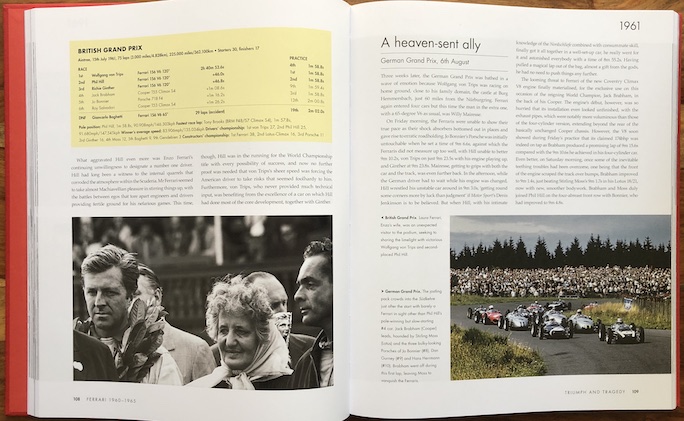

Top left: an experimental 250LM with streamlined rear.

Each racing season takes up some 50 to 60 pages and begins with an overall summary of key developments, both in the sport and at Ferrari, and then covers specific events one by one, with race results arranged in tables. It would be wrong, or pointless, to say that there is anything new in this book, but then that is not its purpose. What counts is that what’s in it be accurate, and what elevates it is how well the narrative is enhanced by the plethora of period photos by Bernard Cahier (1927–2008) who shot his first GP in 1952, the year his son Paul-Henri was born, who would also become a photographer. Being among the early professional motorsports photographers made him a steady presence at events, and working at a time when every aspect of the sport was several sizes smaller and more familial than it is today gave his photos a proximity not just to the action but to the personalities that, as Huon rightly laments, is on a whole different order than the ones “curated by marketing people” in the modern era. The Cahier Archive contains some 400,000 images plus many items of memorabilia, and will yield not-yet-published imagery for years to those who know where to look. The photos here are so thoroughly captioned that, if you were in a hurry or on a subsequent refresher run, you could just read them and get a cohesive understanding.

You’ve seen a thousand photos of cars but what really brings back a past era is seeing the people.

The book has a fine Index, and whoever did it deserves special praise because it consists of only proper names—and in cases were people have established nicknames those are listed as well (example: ‘Elde’ — see ‘Dernier, Léon’). Joy.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter