L.A. Birdmen, West Coast Aviators and the First Airshow in America

by Richard J. Goodrich

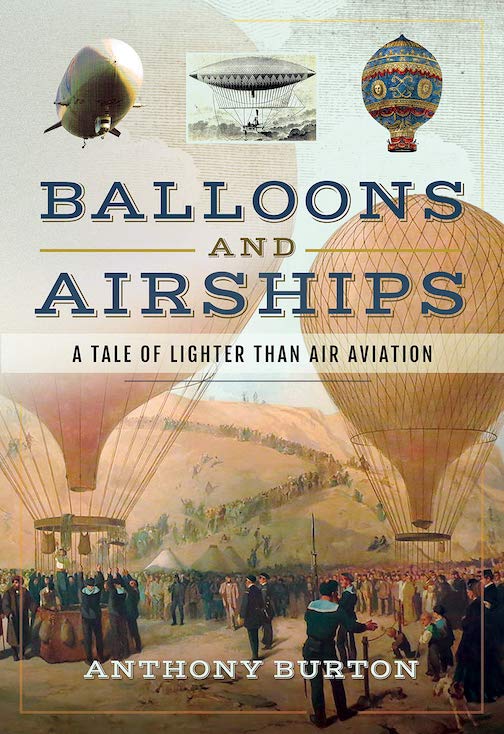

“A yellow monstrosity, a bulging tuber, crawled across the sky with the elegance of a constipated wasp. Viewers struggled to name what they saw. It wasn’t a hot air balloon, drifting before the wind with a basket at its base—the shape was wrong. The silk envelope lay on its side, a giant sweet potato longer than it was tall. A wooden frame swung beneath the flapping bag, suspended by a cat’s cradle of ropes. Twin propellers spun, one on each side of the airframe. Two thousand feet above the city’s buildings, August Greth, the machine’s inventor and pilot, waved gaily at his growing audience.”

If names like Greth, Zerbe, or Knabenshue have already been on your radar you’re playing with a fuller deck than most early-aviation enthusiasts.

The scene above plays out in August 1903, and maybe it’s only the proximity of that data point to the Wright Brothers’ first flight two months later that propels author Goodrich to begin his book with a good number of pages exploring their exploits even if that is essentially a side issue to the story he’s really after—or maybe it’s his angle of wanting to pursue, as his blog says, “stories that never made your high school history textbook.” What the Wright episode does establish, indirectly, is that in an aviation context the question Who’s First? has multiple answers and they depend on what was being flown.

Then, too, it is noteworthy that the Wrights’ reasons for eschewing publicity (what Goodrich describes as “a retreat into taciturnity”) really is a key reason the national press remained bitingly skeptical of their claims—as august a magazine as Scientific American professing a “lack of interest” in “uneducated bicycle repairmen”—of having built and successfully operated a fully maneuverable, powered, heavier-than-air flying machine. Of course it did not help that the press got the initial reporting all wrong, one newspaper going so far as to print side by side two entirely conflicting reports of “the monster bird” that had “flown three miles,” leaving it to the public to sort things out or to simply put the matter out of their minds.

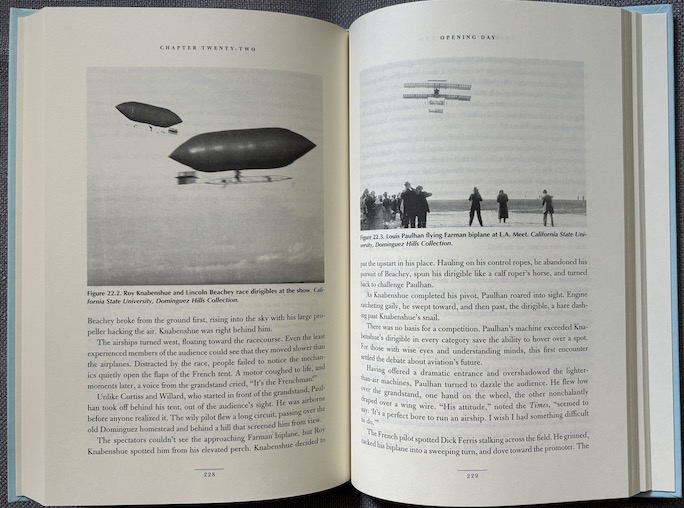

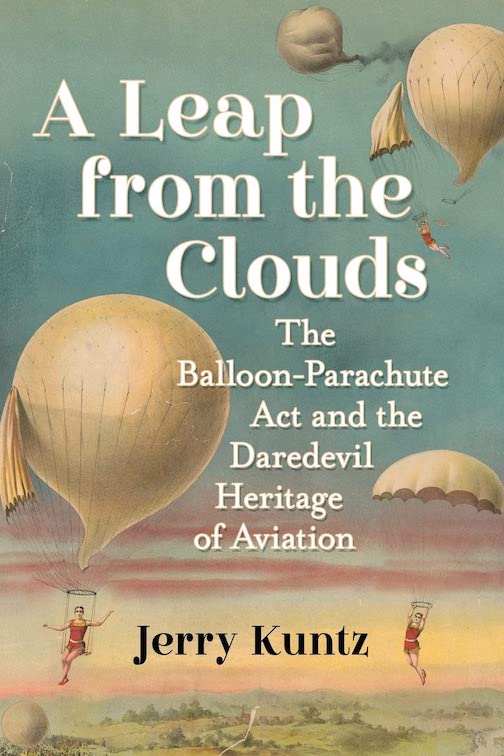

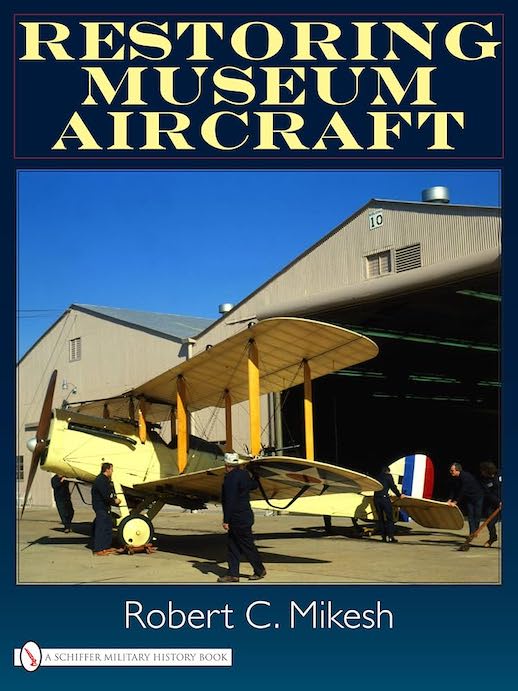

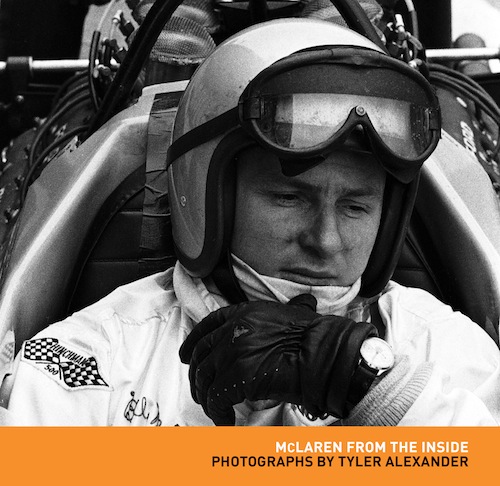

Many pages after these photos comes a paragraph that fits well:

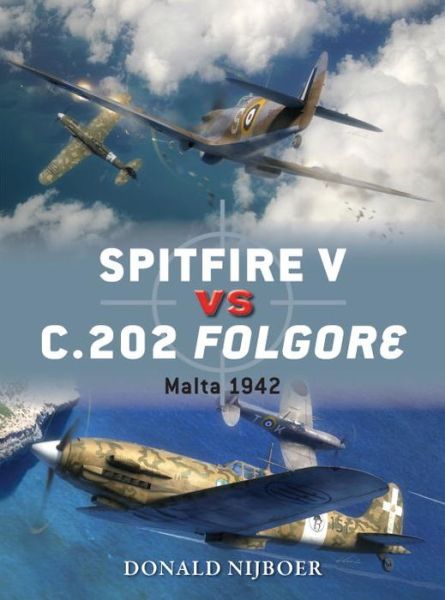

“The air show was a revelation for a nation whose previous experience with flight had been limited to lighter-than-air vehicles. Beachey and Knabenshue [left] jousted admirably at the show, but even the meanest intelligence recognized the superiority of the heavier-than-air machines. Balloons and dirigibles were outmatched in speed, maneuverability, and the ability to fly against the wind. Moreover, they failed to offer the drama that held a fickle audience’s attention. As Charles K. Field observed, ‘The crowd, though cordial, was not here for the balloons. Interest centers in the heavier-than-air machines. Men have been lifted from the earth by heated air and by gas for many years—the world has been waiting for them to rise on wings.’”

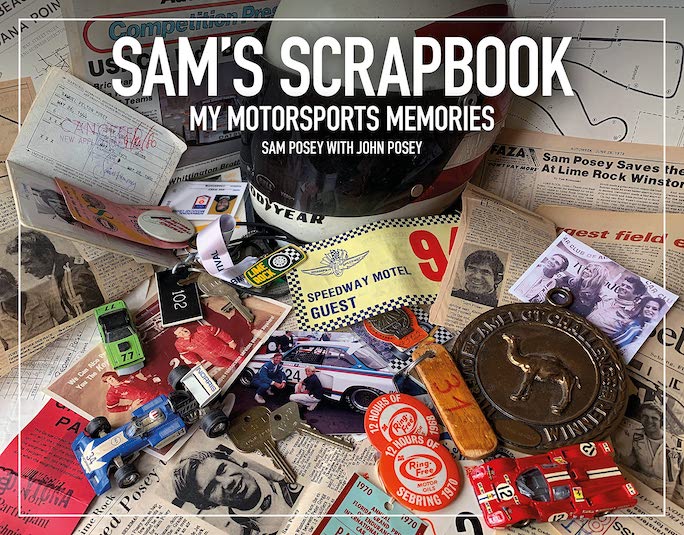

Goodrich describes American and concurrent European developments, specifically France where pioneering work on hot air balloons had been done. These busy years culminated in that airshow referenced in the subtitle: the 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field, hailed by a local paper as “one of the greatest public events in the history of the West.” (The Wright Brothers did not take part, instead pressing a lawsuit over patent infringement, but they did participate in the next big meet, the Harvard-Boston Aero Meet later that year.)

If the flowery prose in the excerpts above cause you to wonder if verbal fireworks take precedence over sound scholarship, realize that Goodrich is in fact a properly serious academic. As a university-level specialist in ancient history (retired) he knows the tools of the trade perfectly well; it’s just that he also knows when “popular history” does not require or even benefit from them. You have to look no farther than his explanation here of how the end notes are structured. His previous book, Comet Madness: How the 1910 Visit of Halley’s Comet (Almost) Destroyed Civilization (same publisher, 2023) is equally engaging.

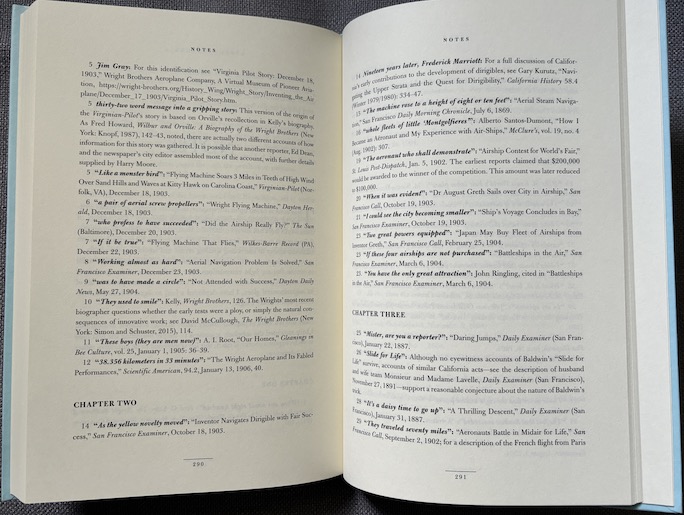

This publisher has several imprints, and they all do chapter and end notes differently. (To be sure, gold star for doing any kind of notes!) This book has end notes and as you see here they are by chapter but numbered consecutively. To the power user this approach has no downside. But now consider that those numbers don’t actually appear in the body copy itself, nor does any other visual cue, meaning the reader is not made aware what part of the text may have a note attached to it. In other words, this book works only “backwards,” from notes back to main text. There are ways to make that work . . . but it’s not this one: the notes boldface key words or phrases that you are then forced to search for in the chapters, line by line, page by page. Do that 10 or 20 times and see what that does to your blood pressure!

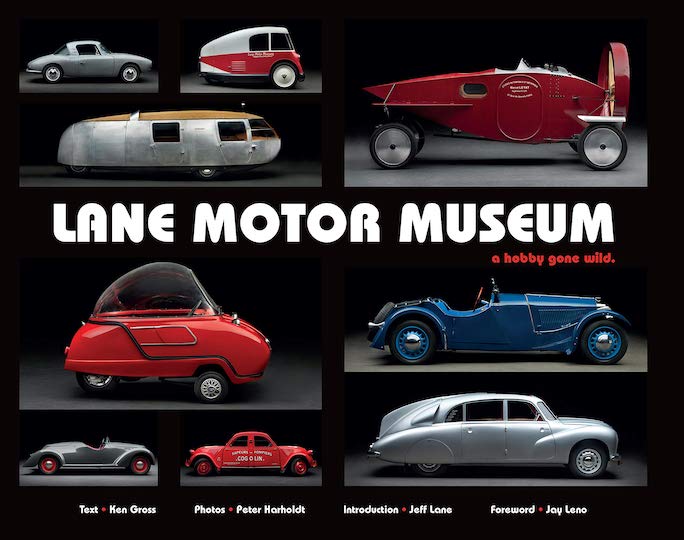

This publisher’s books are generally not lavishly illustrated, mostly because the type of paper just doesn’t lend itself to it. There are only 21 images here, and there is no Bibliography (or Index) so you will have to look elsewhere for a fuller picture.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter