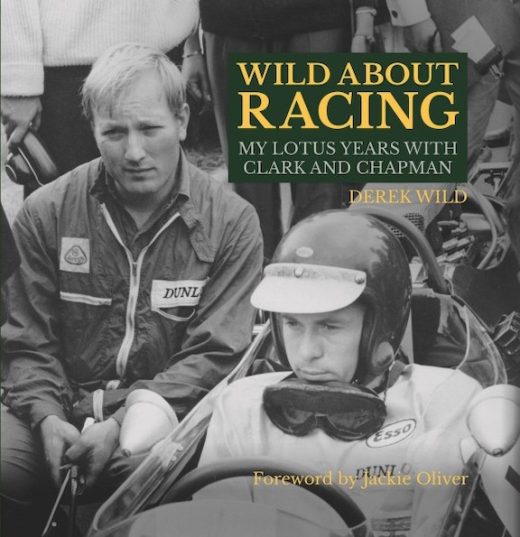

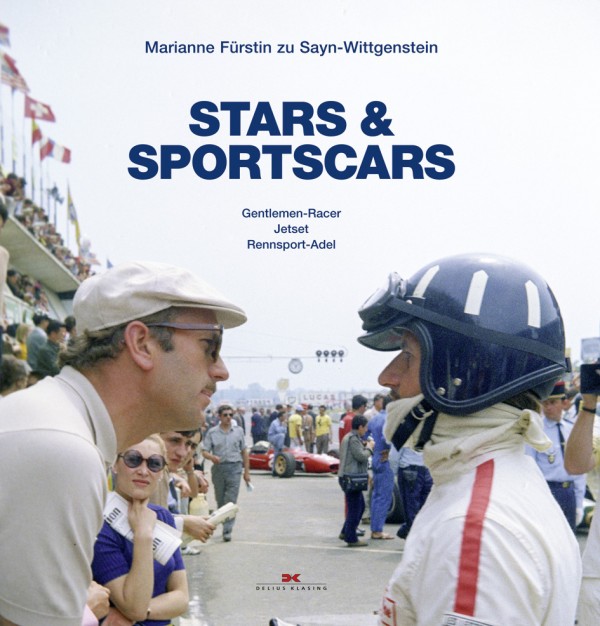

Wild About Racing: My Lotus Years with Clark and Chapman

by Derek Wild

by Derek Wild

“The mechanics had to drive the Formula 1 cars to the circuit through the town [Reims], contending with traffic lights en route, as well as the local ‘racers’ wanting to race us.”

This short, 132-page book will achieve two things. For older readers it will rekindle memories of Team Lotus’ glory days. For anybody under sixty, it will evoke an era in motorsport where glamor was tainted by tragedy, and perhaps even enhanced by it?

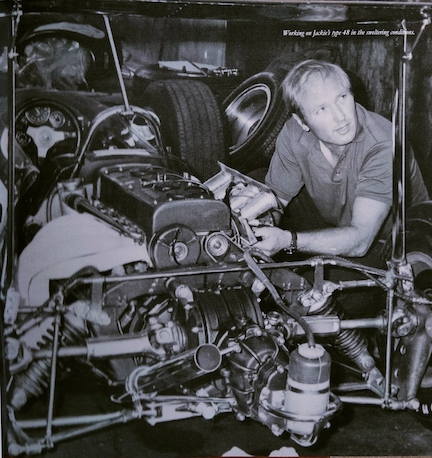

Derek Wild worked as a mechanic for Team Lotus in the Sixties, and his first-hand account gives an insight into the decade where greater progress was made in race car design than ever before—or since. Now in his mid-eighties, the author has written an entertaining and informative account of his years with Lotus.

Wild started work for Lotus when it was still based in modest premises in Cheshunt, just outside London. Nowadays there are college courses in motorsport engineering so it’s extraordinary to read that, in 1960, part of the author’s interview at Lotus involved checking over a Coventry Climax FPF Formula 1 engine. He did it successfully and started work the very next day—human resources departments weren’t even a thing in the days when Harold Macmillan lived at Number 10, Downing Street.

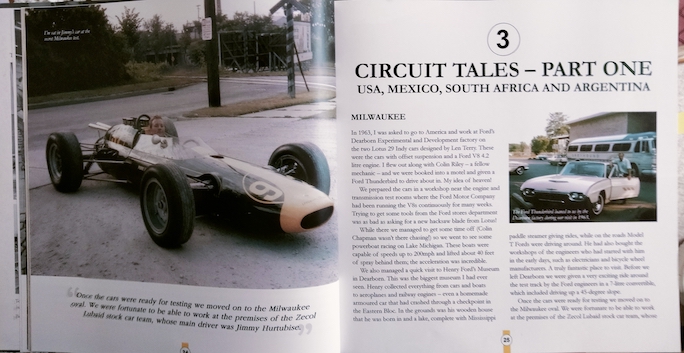

The themes of the ten chapters include “Safety Issues,” “Memorable Lotus People,” and three chapters entitled “Circuit Tales.” The latter covers circuits from Milwaukee, where the Lotus 29 Indy car was tested in 1963, to Rouen Les Essarts, where the circuit was demarcated by straw bales, and Snetterton, the former USAF bomber base located a short drive from Hethel, Lotus’ base from 1966.

The book is a mosaic of anecdote and reminiscence, and themes notionally belonging to one chapter often reappear in others but that’s no bad thing. The abiding impression, and an endearing one, is of the reader having been in the company of an older man keen to share his memories, with an urgency reflecting the decreasing number of first-hand witnesses of Formula One in the Sixties. As I write, the drivers are down to a handful, including Stewart, Andretti, Attwood, and Ickx. And Jackie Oliver, who seems to appear in most books I’ve read this year. He writes the Foreword here, and is well placed to do so, as Wild was his Team Lotus mechanic for four years and his Lotus Components’ dedicated mechanic in 1966–68.

The 2024 World Championship has an unprecedented 24 races, including six sprint races. Back in 1963, the championship was contested at only ten World Championship Grands Prix. But the author reminds us that, in that season, Jim Clark contested twenty Formula 1 races, in twelve countries on four continents. That meant long trips in transporters for the Lotus mechanics, and there are anecdotes about wheezing Bedford transporters struggling to cope with steep Alpine descents, and of the Flatback Ford 400E’s 90 mph cruise destroying tires en route to Sicily’s Enna Pergusa track. You remember the one, notorious for the snake-infested lake in the infield?

A Formula 1 tire change now involves up to 20 pit crew but in the Sixties, race teams were tiny. We learn from Wild how much multi-tasking and overnighters that involved, but a mechanic’s life was annealed by esprit de corps and punctuated by practical jokes, hangovers, and the occasional arrest. Mention of the once popular jape of setting off oxyacetylene bombs reminded me that the last time I heard one of those was in the Ensign garage at Silverstone in 1979.

I’m as guilty as I suspect Wild is for remembering a past that was possibly less rosy-tinted than it seems from our perspective, but it still sounded such fun. While I was falling asleep in Latin lessons Wild literally was setting up Jim Clark’s Lotus 25 for (yet) another victory. He’d first encountered Colin Chapman when the garage he worked for did the servicing on Chapman’s Raymond Mays-tuned Ford Zephyr tow car. And as soon as his apprenticeship was over Derek got his dream job and worked with the names every Lotus tifoso knows by heart—Jim Clark and Graham Hill, Bob Dance and Jim Endruweit, Graham Arnold and Andrew Ferguson. Mike Warner too, with whom he formed Group Racing Developments in 1971, better known as GRD, maker of F2, Formula Atlantic, and F3 race cars. Arthur Hobern was a Lotus name new to me but he stood out in Derek’s memory. Because this talented gearbox engineer had also been a lion tamer, and his wife an acrobat and unicyclist. Not too many of those in the Red Bull F1 team I’ll bet.

Wild spent much longer with other race car manufacturers than he did with Lotus; he worked at GRD and Modus before spending 35 years at Van Diemen as Development and Production Manager, working with drivers including Senna and Schumacher. But it’s Classic Team Lotus he still visits, and that in itself is testament to the Colin Chapman legacy.

This is a charming book written by a likable man. The book is relatively short, and if the detail sometimes is a little lightweight, maybe that’s because it’s in keeping with Lotus’ most famous characteristic?

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter