Ferrari in America: Luigi Chinetti and the North American Racing Team

by Michael T. Lynch

by Michael T. Lynch

“The European market for racing and sports cars tended to be along a spectrum ranging from those fully invested in competition to those less so. American palettes [sic] tended to bifurcate between people engaged in competition and those for whom the sports car was a pleasurable and exhibitionistic transportation. Chinetti coached Ferrari into meeting some of these demands. The communication was not always smooth. There were often problems in the pipeline. Many could be attributed to uneven build quality, metallurgical issues, and the volatility of Italian labor.”

There is a lot packed into that opening excerpt and it hasn’t even mentioned NART yet, the North American Racing Team that did as much for Ferrari’s market penetration as its operator, Luigi Chinetti Sr., did for the development of a strong private customer base in the US. Either one of these factors is of tremendous importance to the fortunes of the firm and author Lynch ably paints a better picture of both than anything that has come before.

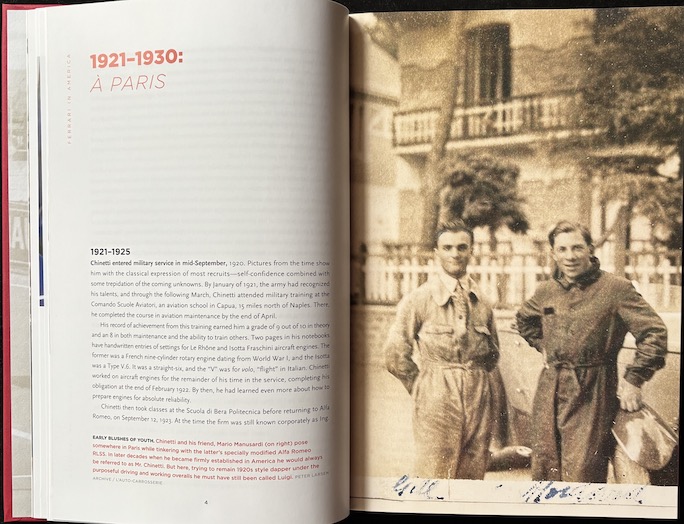

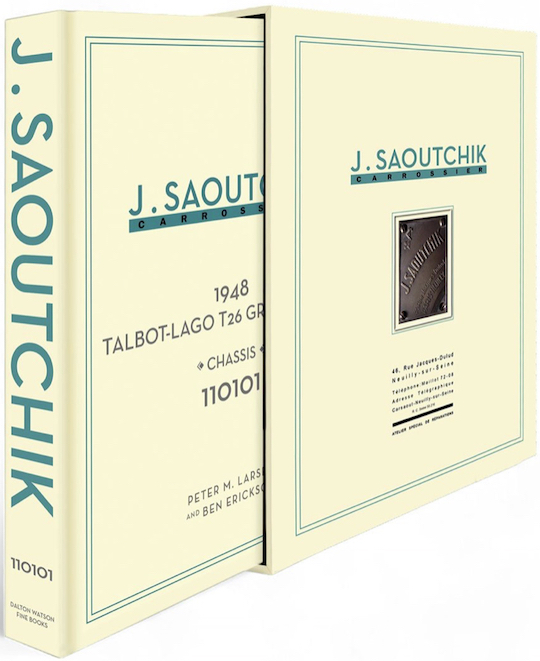

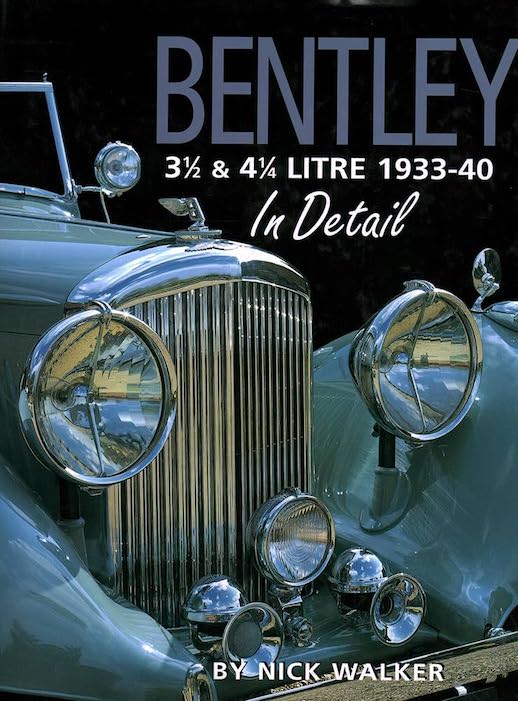

Photos are sourced from a great variety of sources, which speaks to the fundamental collegiality among book folk. This is one of several from Peter Larsen’s archive, he of the many bookshelf-bending coachwork books, all of which reviewed here.

The casual reader may need to be reminded that those two separate strands—racing v road cars—were in Enzo Ferrari’s case uneasy bedfellows. Unlike, say, Porsche, he saw the building and selling of road cars merely as a means to the one end that mattered most to him: a successful and ideally indomitable racing operation. And the timeline has to be remembered: in postwar Europe the battle cry was “export or perish” so getting into the heads of US customers who just wanted a fancy—and reliable—European sports car was on the one hand a distraction for Enzo Ferrari but also vital. Lynch makes a point early on of establishing why Ferrari and Chinetti related relatively well to each other, their “oversize personalities” notwithstanding, so that the reader can appreciate why Chinetti (b. 1905) was appointed as official Ferrari distributor for [most of] North America, thereby influencing the fortunes of the firm in a lasting manner.

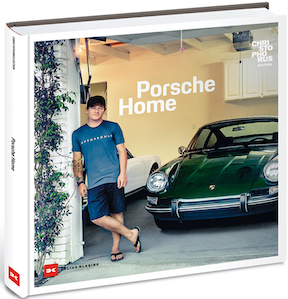

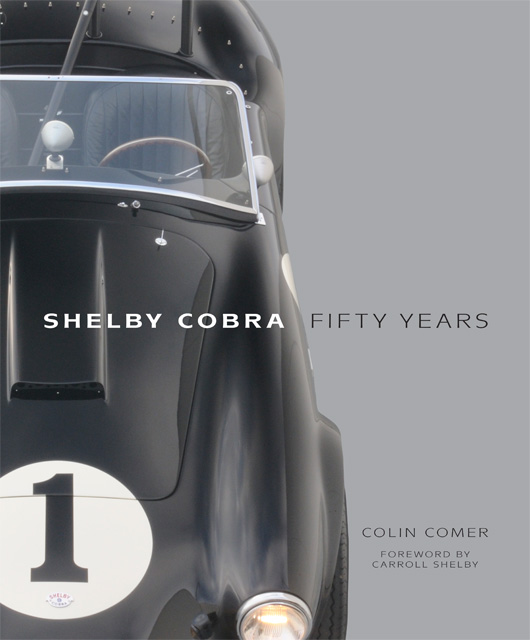

You can’t tell from this photo but the book intentionally is of a smallish size (it’s all relative: 10.5 x 9.5″) for this type of book, the idea being to make it comfortable to hold when sitting in an armchair—provided the 5 lb weight doesn’t snap your wrist—which connotes a different atmosphere from siting at a desk with pen and paper to hand. Even page layout and typography are “calm” not “shouty” (a book ribbon would have fit the picture quite well!) and it is a given that a David Bull book will be nicely printed and bound.

This sensitivity towards setting the scene is why the book, in at least two places, emphasizes “Michael didn’t write exclusively for car enthusiasts, but for anyone who likes a good story.” To that end, there is no shortage of background and connective tissue, in fact the book starts as far back as 1850 with the political and related geographic situation in Italy which is relevant insofar as it affects three generations of Chinettis.

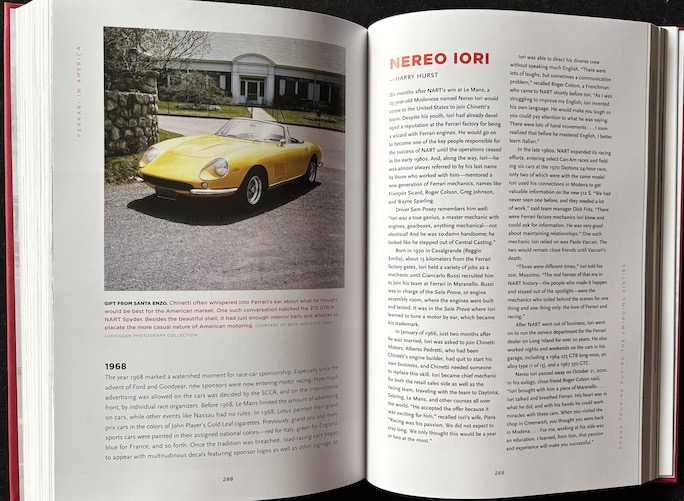

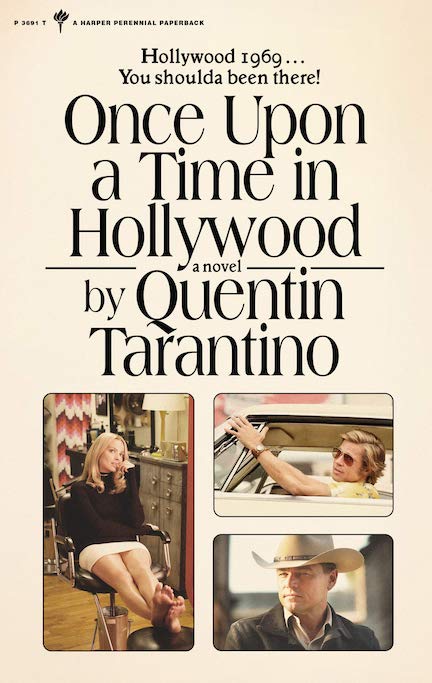

The captions could obviously not have been written by Lynch. They do have a bit of a different tone or choice of words but the message is no less clear, here “Chinetti often whispered in Ferrari’s ear about what he thought would be best for the American market.” The mere idea of anyone thinking Ferrari had an ear that could be whispered into would have infuriated him but in this case this was a matter of earned privilege. The two men had known each other for decades by then, having gotten their start, at Alfa Romeo, within two years of each other, Ferrari as a racing driver and Chinetti often ”acting as machinist and mechanic, sometimes working for the racing team.”

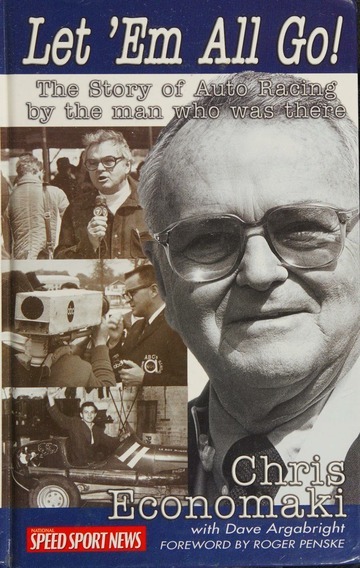

The book contains several bios (r) that are written, along with some other bits, by motorsports historian Harry Hurst, colleague of the late Fred Simeone who did so immeasurably much for the preservation of important racing cars.

There is neither a need nor a point in dissecting specific minutia in the book after establishing that Lynch’s bona fides in the Ferrari world go back to the 1970s and that in time he ventured into all manner of motorsports and automobile topics, garnering awards and being elected a Member of the IMRRC Historians Council. He was of a scholarly disposition, well-respected and well-connected—the right ingredients for writing a meaningful and relevant book. What muddles the waters here is that not all components of the finished book are his doing—because he was no longer alive then and different people were tasked with attending to different aspects of the book.

So, a side issue begs to be considered:

We always strive to consider a book as it is, not what it could have been. Except in this case that’s the elephant in the room. In certain circles, a definitive Chinetti/NART book is the hottest ticket in town because it had been whispered about for years and years. In our review of the last and pretty much only meaningful book on the subject, Terry O’Neil’s N.A.R.T.: A Concise History of the North American Racing Team 1957 to 1983 (2015), we remarked that many more layers of context remained to be introduced into the record and that in fact there was just such a book “rumored” to be in the works. That was what would become this book. (There also was a NART book spearheaded by Graham Gauld but that never took concrete form.)

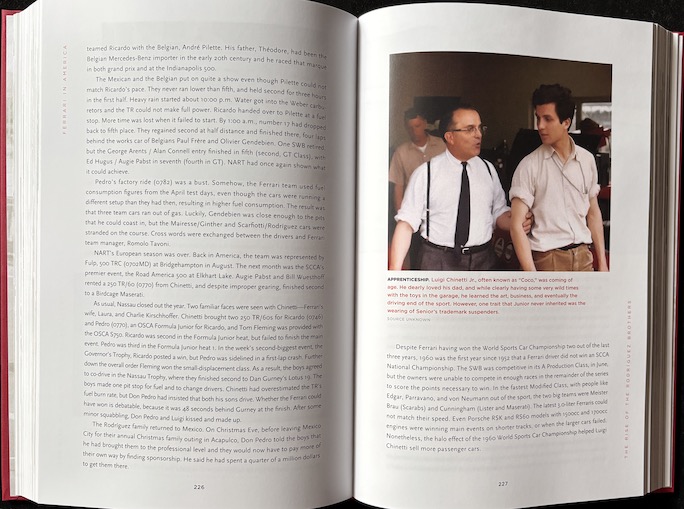

Chinetti Sr. and Jr. The book is rather too circumspect about their not wholly easy relationship. The caption says of Jr. “he dearly loved his dad,” which he may well have but there is a reason Luigi Sr. was so respected that all his life he was addressed as Mr. Chinetti whereas Luigi Jr. was known as Coco to most and called names not fit to print by others.

By 2016 Lynch had approached Luigi Chinetti Sr.’s son, keeper of the vast Chinetti family archive, who was keen on having his parents’ story (Luigi’s wife Marion played a crucial and active part) comprehensively told and was thusly highly motivated to supply information, photos, and documents so as to make this book the last word. Great plan.

Except . . . Lynch died (2019) three years into the project, leaving behind a mostly finished text to which Chinetti Jr. is known to have had significant input but the manuscript hadn’t moved into the next phase, fleshing it out with archival and illustrative material. Why that never came to pass makes a complicated matter more complicated: the publisher, David Bull, had died as well (2021) leaving the future of the company in limbo for some time. By the time there was a path forward, Chinetti Jr. no longer felt he and the DB successors were on the same page as to scope and style—and instead elected to offer his material and cooperation to a new publisher. That book, a multi-volume affair titled LUIGI CHINETTI – His Saga, Alfa Romeo, NART and Ferrari in America, is currently being written, by Doug Nye.

When it rains, it pours, eh? A subject that had lain fallow for years will now be covered by two books, by two able authors, but only one, Nye’s (Porter Press) can lay claim to being the “only official, authorized book on the Chinetti dynasty.” You might think that the inevitable question is going to be which one is “better”? Wrong question. Or at least unproductive; both are worthwhile. Right this moment the Lynch book has of course the unassailable advantage of being first (although there is a whiff of undue haste re matters of small detail) but it is missing the troves of heretofore unpublished primary-source material from Chinetti Jr. who is not even recognized in the Acknowledgements. Not a single image or document, each being credited right in the captions, is from him. These words may smack of acrimony but let it be known that Lynch and Nye had a respectful and friendly exchange of ideas, including on the Chinetti/NART topic, which is a roundabout way of saying once more that both books have purpose and value.

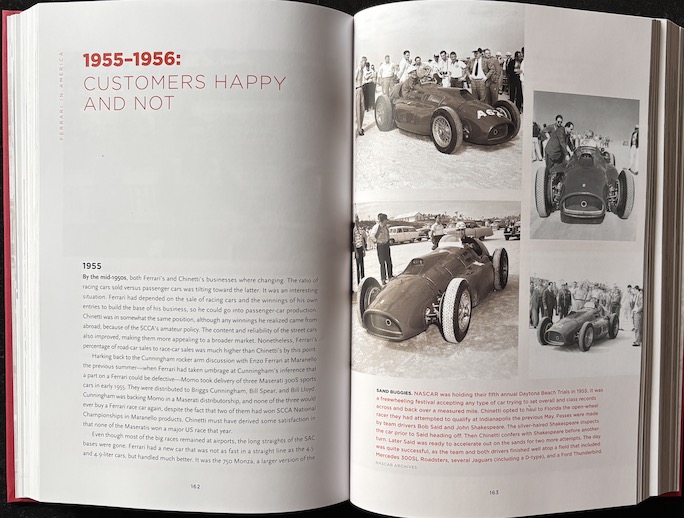

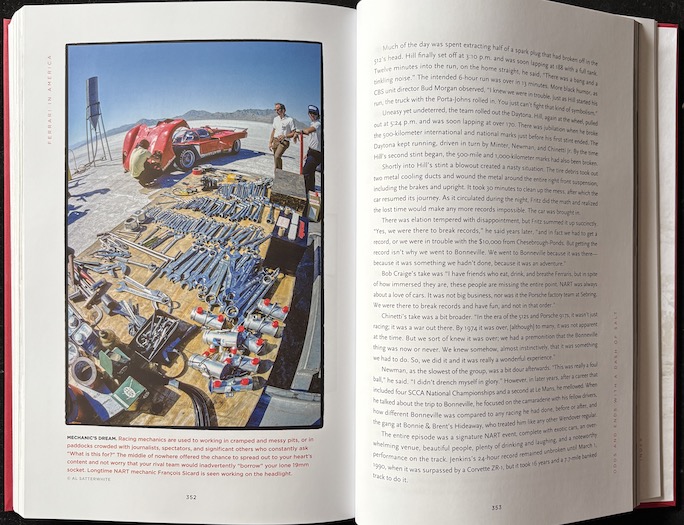

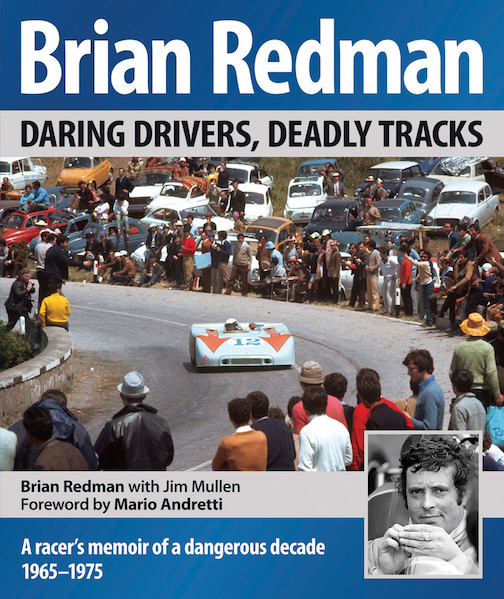

Such a great shot. If you know your photographers you can’t be surprised to learn this one is by Al Satterwhite.

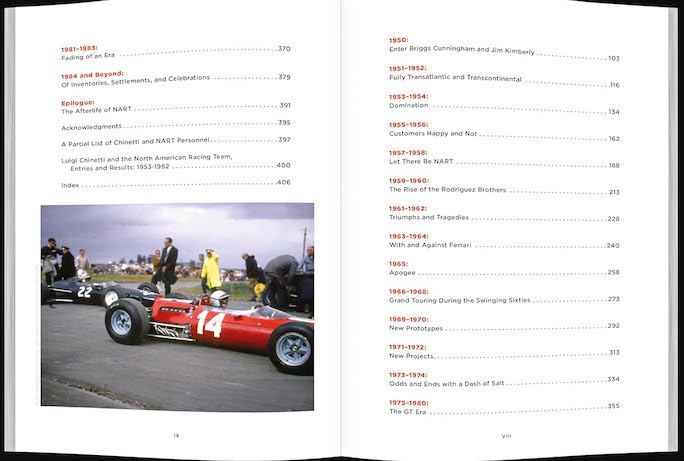

The book ends with a partial list of Chinetti/NART personnel (idle chatter has it that one of them may be doing a book of his own), a table of 1953–58 race entries and results (presumably by János Wimpffen who also wrote the Introduction), and a grand 14-page Index that makes it easy to really work with the book, as does the precise Table of Contents.

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (Speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter