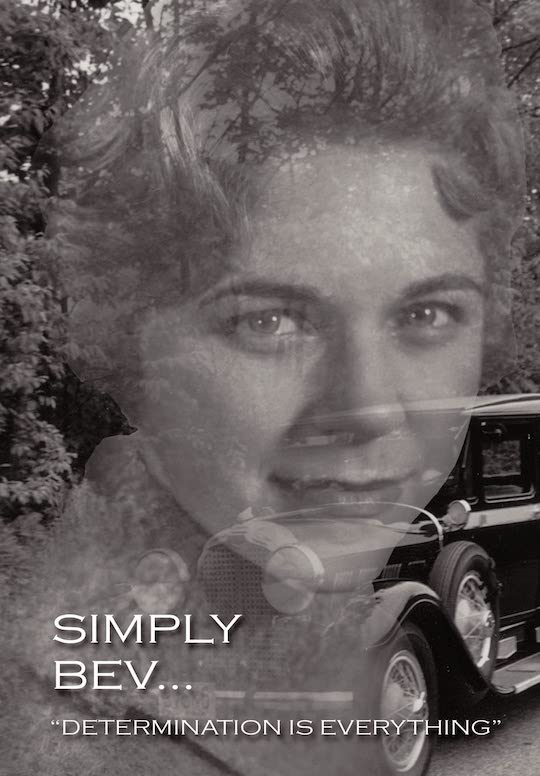

Simply Bev . . . “Determination is Everything”

by James H. Cox

by James H. Cox

Often enough books are described as “a labor of love”—by which is meant a love for or of the subject sufficiently compelling to shoulder the burden of writing a book. Certainly this is true in this case, except that it couldn’t possibly have been a “burden” since its subject is a flesh and bones human being.

Not just any being, but the author’s wife. Or, rather, late wife (d. 2008), wherein lies all the grief and all the joy that is unique to the existence of a sensate being.

To those who knew her, and this writer did have that pleasure, automotive historian Beverly Rae Kimes, diminutive though she was in stature, was a giant among wo/men. Not just as a scholar—she herself would be the first to insist that anyone, in principle, can apply him- or herself in like manner to the great matter of learning and learnedness—but rather in the fortitude with which she did not allow a body that had been failing her since early in life to deter her. It touched the heart and stirred the soul and made one bemoan the capriciousness that cares not whom it befalls.

One supposes that writing about a life partner must be cathartic, all the more so since Cox and Kimes got married relatively late in life (1984), thus having had time to rack up “a past” as individuals. This sounds unduly theatrical—which Kimes would have appreciated since the theater was her first love and she envisioned that field as her future professional endeavor. In his Foreword, Cox explains that she never discussed her youth much (spoiler alert: no skeletons in the closet; it just wasn’t her thing) and while he was familiar with the highlights it wasn’t until he went through the piles of notes she left behind that he himself got to know new sides of her. In this discovery lies the genesis of this biography. Cox rightly felt that enough had already been recorded about her professional life, with more surely still to come, and wanted her audience to have an opportunity to meet the “Girl on the Go”—her own way of referring to herself early in life.

That Cox was able to piece this puzzle together is thanks to the copious notes Kimes kept about anything and everything already as a young girl. From letters to school prizes and menus to theater bills, chances are she [a] saved it and [b] stuck a note to it recording the circumstances and her thoughts about it. (6-year-old Bev: “First prize I ever won, for Pin the Tail on the Donkey, in Feb. of 1945.” Why did she keep an unopened package of Twinkies for 50 years? Read the book!) For the reader who only knows Kimes as the arch scholar the important thing to realize here is that she did this habitually, unselfconsciously, as a child with no inkling of her future “name.” She is lauded for being an exemplary researcher, which implies making, keeping, and finding records and even though her professional career depended on her becoming very good at it, it is a habit she developed seemingly without prompting or reflection or even specific application.

Kimes’ biographers and obituarists unfailingly see the hand of fate in an admittedly colorful event in her life that would end up opening a new chapter. It makes great copy and is the sort of thing that seems almost too good to be true: her waltzing into Scott Bailey’s Automobile Quarterly office, then only in its infancy and far from being the industry benchmark it would become, and asking for a job at a car magazine by announcing “the only thing I know about automobiles is that I have a driver’s license!” True enough, but missing the very detail that was her stock in trade: she was sent on the interview by an employment agency and she considered the AQ gig strictly temporary, “something that would look good on my resume” for when she found the job she really wanted. Cox attributes her staying at AQ, which would result in her working her way from editorial assistant in 1963 to Editor in Chief 1975–1981 and also running the magazine’s book division, Princeton Publishing Co., to her becoming acquainted with AQ contributor and Long Island Automobile Museum owner Austie Clark. This and a thousand other details accomplish just what Cox had wanted for this book.

Divided into chronological chapters (but there is no table of contents) Cox tells the story in the form of individual, often unconnected vignettes. Think of someone going through a scrapbook or pulling mementos out of a shoebox and talking about them and you get the flavor of the book. In other words, there is no continuous narrative or the sort of appraising commentary one might expect in a biography. Following her through early childhood, parents, friends, school, university, career, marriage and business ventures with her husband (auto restoration, a toy store, the book they wrote together, an antiques business) and her many professional accomplishments we get a glimpse of Kimes’ various interests, personality traits, and outlook on life. The story does not always remain linear and there is some skipping around. A bit more jarring is that the photos are not always quite in synch with the chronology. Rather disappointing is that they are exceedingly small, 1 x 2 inches on average.

For a self-published book it has remarkably high production values: hardcover, dust jacket, even headbands. It is, however, sad to have to note that the book is absolutely crawling with typos—rather ironic in an homage to someone who was all about the written word and “getting it right.” On the other hand, what’s the lesser evil: no book at all or one written by someone who didn’t let the fact he’s not a professional writer deter him? Everyone has their area of expertise and, if you don’t know it, realize that Cox’s shop Sussex Motor and Coach Works in its 17 years of existence turned out many an award-winning restoration! That, too, would be a book worth writing, to which Cox says “. . . the only things you will ever get to know [about me] will be what I tell you, so pay attention!”

Appended are a talk she liked to give about early cars, the story behind the “Girl on the Go” moniker, and a list of awards and citations.

It is not appropriate to reproduce it here, or weaken its impact by excerpting from it, but a prayer of hers as a young girl (p. 18; her family was Catholic) is almost hauntingly prescient—and so this review ends with as heavy a heart as it began. What relief there is couldn’t be expressed better than in the words of her motto in the subtitle.

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter