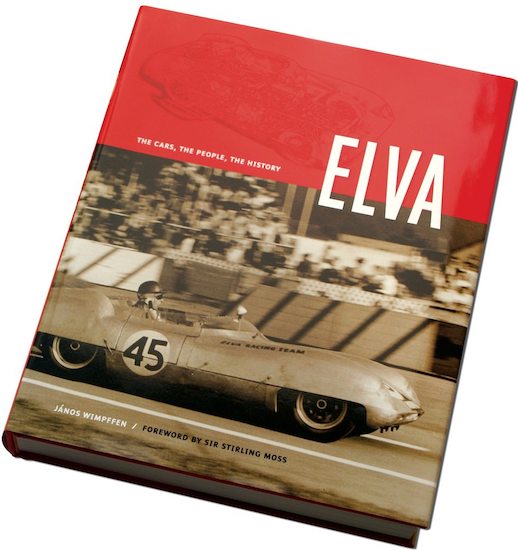

Elva: The Cars, The People, The History

by János Wimpffen

by János Wimpffen

If you’re a car, ELVA—she goes, in French—is better than NOVA (as in: Chevrolet)—doesn’t go, in Spanish. And go the little English car with the French name certainly did but the company did not, at least not for long. Still, its more than a decade-long run surpassed that of its 1907 (unrelated) namesake, Voitures Elva of Paris which lasted only one year and produced all of two cars.

Even in its own day, Elva was hardly a household name. Certainly not in its home market despite decent racing success. They were better known in America where the racecars acquitted themselves well and the road cars rang up solid sales. Many contemporary British marques had similar cottage-industry beginnings and of the ones Elva diced with—Cooper, Brabham, Lotus, Lola—only the latter two survive to this day and even that in only a form so different from its origins that it hardly lends itself to comparison to Elva’s fate. This great conundrum of why some survive and others don’t is one of the recurring themes of this book about a marque the author calls “magical.”

Today, outside of vintage-racing circles the Elva name is all but a footnote. Wimpffen’s book cannot really change that but it will give Elva owners and enthusiasts at last a definitive account of the marque’s origins and life cycle and also the people behind it.

Readers who don’t already recognize the author’s name as one of the heavyweights among writers of a certain caliber of book have a lot of catching up to do. All his books live on that rarefied plateau of indispensable, constantly consulted, reliable reference works. There are not many of them, and how can there be, considering the incomprehensibly arduous task of turning over every stone to gather facts.

People in the book world are aware of all sorts of manuscripts that are “in progress” at any one time. Not all of them come to fruition. For years, occasional inquiries of Wimpffen’s on Internet message boards were the only sign to outsiders that the project was, indeed, still alive. Seeing this long hoped-for book finally done, and done so well, is a treat. It cannot have hurt to have someone like businessman Bruce McCaw as patron—and cheerleader/prodder. McCaw, who crashed his first car at the tender age of 2½, bought his first Elva racecar sight unseen on a friend’s recommendation in 1968, long before all you cell phone users proved his and his brothers’ idea of leasing “airwaves” from the government to be the golden goose of the modern age (McCaw Cellular was bought by AT&T in 1993 for a cool $11.5 billion). He still owns that first Elva and bought others along the way; more importantly he got to know Elva founder Frank Nichols (d. 1997) in the mid 1980s and learning more about the man and his cars resulted in a lasting friendship of which one fruit was McCaw’s promise to see to it that a proper Elva book would be written.

It is difficult to fathom that except for several Brooklands Road Test books and a few dozen magazine articles the existing Elva literature should be so painfully thin. The firm pioneered various innovations and improvements and earned the respect of its peers (they were the first chassis builder Porsche allowed to use their racing engines, McLaren asked them to build their customer cars etc.). It wasn’t long after closing up shop, having built about a thousand cars, that “Father Frank” saw the wisdom of creating an Elva Owners Club and supported Roger Dunbar in the UK in such an endeavor. Over the years, Dunbar, who still runs that club and in many other ways is the keeper of the flame, gathered material for a book—the book. Joining forces with Jeff Allison who as then associate editor of Vintage Motorsports (he’s been editor of the Ferrari Club of America’s quarterly magazine Prancing Horse since 2003) was acquainted with Nichols, the manuscript grew to some 100,000 words (say, 400 pages) and around 750 photos. It was to be called The Cars Just Happen – The Story of Frank Nichols & Elva Cars. Remember the comment above about manuscripts that book people know are out there in some shape or form? Well, the Dunbar/Allison project faltered at some point—and then the McCaw/Wimpffen/Bull triumvirate stepped up and committed, respectively, dollars, writing skill, and publishing muscle to the cause of using that earlier work as the basis for the definitive book McCaw had once promised Nichols. Wimpffen considers Dunbar/Allison co-authors even if they are not listed as such.

Wimpffen is both arch statistican (how a doctorate in geography leads to a professional life in the transport-consulting field [don’t ask!] let alone to writing award-winning motorsports books is anyone’s guess) and honest-to-goodness racing enthusiast who used to fling a Triumph around Elkhart Lake’s Road America circuit in his younger days. The tenacity, attention to detail, and lack of fear of vastly complex subjects he exhibited in his first book Time and Two Seats, and practiced through the next four, is what elevates this newest book.

Wimpffen tags the firm as “far from the best of the breed and far from the worst”—but also “not mediocre.” You can seen how this is going to be a difficult a story. What is it that Elva had in common with its contemporaries, and what is it they did differently that would account for their different fortunes? There is, 450+ pages later, no conclusive, inevitable answer. Racers know this; entrepreneurs too: you can give it your all but without luck it may all be for naught. Wimpffen paints a rich, dense, nuanced picture of the people who tried, and of the chassis, parts, and bodies they conceived, and of the business decisions they made and the friends and foes that crossed their paths.

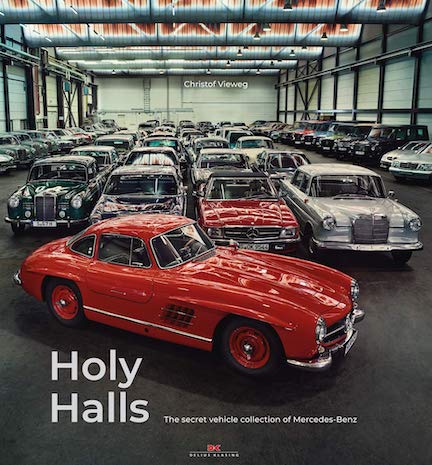

The book is supremely well illustrated. (A novel approach to the age-old dilemma of how to relate captions to photos without letting their placement on the page interfere with layout choices is to number each, thus removing any ambiguity as to what goes with what even if photo and caption are not next to each other.) This wouldn’t be a David Bull book if paper, printing, typography and photo reproduction weren’t top-shelf. But, giving an almost 2˝-thick book a flat spine is an affront to bookmaking—the power-user should not expect it to become an heirloom.

Four Appendices offer an “approximate” timeline, an explanation of the Master Results Table that is available only as a free 9 MB web download because its 12000+ entries constitute a 572-page (!) pdf, a summary of all known Elva drivers who placed 1st–3rd in championships, and a list of over 2000 drivers who raced in period (i.e not latter-day vintage/historic) competitions. There is no list of chassis numbers (which were quite chaotic). The Index is beyond thorough.

A very nice Introduction by McCaw, and a rather perfunctory Foreword by a “name” (Stirling Moss, who didn’t take a shine to Elvas until his post-pro career vintage-racing days). The Publisher’s Edition of 150 numbered copies—signed by Moss, Chuck Dietrich, Augie Pabst, Bill Wuesthoff; and Roger Dunbar, Bruce McCaw—includes 36 additional pages of Elva brochures and ads.

Won the Motor Press Guild’s 2011 Dean Batchelor Award.

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Very cool, especially since I edited the book!

Great all inclusive book on Elva thanks Janos and Bruce