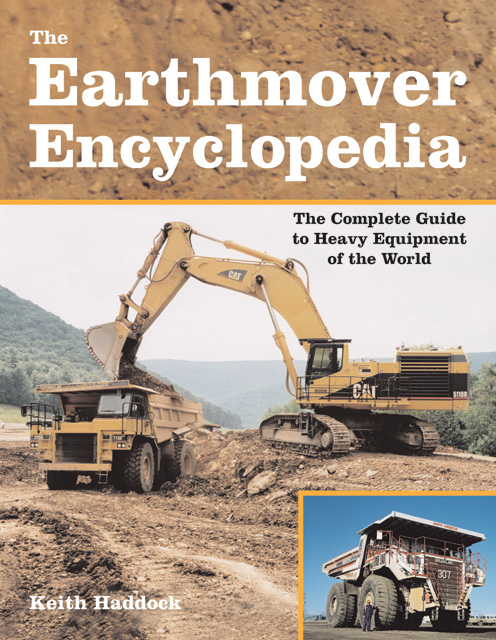

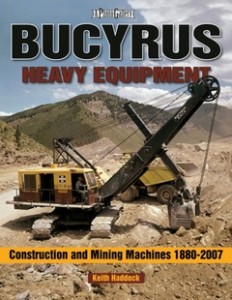

The Earthmover Encyclopedia

The Complete Guide to Heavy Equipment of the World

The Complete Guide to Heavy Equipment of the World

by Keith Haddock

Disclaimer Alert! Upfront I have to say that I used to operate earthmoving equipment, so my interest in an encyclopedia of such equipment may be keener than yours. I know firsthand that operating a multi-ton diesel-powered steel mammoth, once the initial fear wears off, gives you an unforgettable feel of what real power can do, offering operating challenges as involving as any found on a racecourse. You become one with your medium, which in this case is the earth itself. The equipment becomes an extension of your personality and nervous system. Together, you and the machine become a giant artificial life form with you as the brain.

The 954 photos in this book take you into a world of specialized equipment design, highlighted at the very end of the book by the bucket-wheel excavators, “the biggest machines to ever roam on the earth.” How big is big? Well, imagine yourself in sole control of a machine weighing 30 million pounds, capable of excavating 314,000 cubic yards of material a day. (To help you visualize how much volume 314,000 cubic yards is, it’s enough to fill, floor to ceiling, approximately 700 mid-size houses.) Up to 34 different motors are at your command with a total of 36,000 hp, allowing the 12 crawler tracks supporting this science fiction-like juggernaut a top speed of .3 mph. Astounding and amazing are words that come to mind to describe its appearance and operation.

The book opens with an interesting eight-page history of the earliest earthmoving machines. To summarize that introductory chapter, the early days of large-scale railroad building and ship canal construction provided the impetus for designing machines to replace humans wielding picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows. In 1887 the construction of the 35-mile-long Manchester Ship Canal, in England, utilized 97 steam excavators to move 1.2 million cubic yards of earth a month, proving the economic viability of mechanized excavation. The Panama Canal, which opened in 1915, was only possible because of the development of mechanized earthmoving equipment.

Sixteen chapters, covering 300+ pages, break down the world’s heavy equipment into separate categories encompassing crawler tractors and bulldozers, loader-backhoes, scrapers, motor graders, articulated dump trucks, cable and hydraulic excavators, stripping shovels, walking draglines, trenching machines, and the aforementioned bucket-wheel excavators. Each page has two to four pictures of the equipment being discussed, with each picture caption describing the who, what, where, and when of the equipment’s development, along with pertinent facts concerning weight, power, and other data relevant to that particular piece of equipment.

The picture captions also outline the story of the rise and fall of the various companies that built the machines. Just like the early auto industry, the heavy equipment industry was started by dozens of smaller companies, each having a special ability that initially allowed them to prosper. Successful companies like Cletrac, LeTourneau, Best, and Drott Mfg. Co. were all eventually absorbed into global corporate conglomerates like Caterpillar, Euclid, Komatsu, and Terex.

Like all specialized fields, the heavy equipment field has developed its own terminology which becomes familiar to you as you read your way into the book. Dippersticks, twin-and single-stick crowds, shoe grousers, shipper-shafts, center tumblers, walking draglines, jaw-clutch steering, bullclam shovels, nibblers, hoe buckets, and center pintles will all seem like common terms by the time you reach the end of this encyclopedia. It’s also interesting to see design leadership change over time. Various improvements like high-pressure hydraulics or articulated steering take hold as American, Japanese, British, Italian, German, and South African heavy equipment manufacturing firms take turns coming up with the next big thing.

The author, Keith Haddock, P.Eng., is a professional engineer and an expert on surface mining. In addition to writing articles for magazines in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom, he has appeared on television for the History, Discovery, and Learning channels. He worked 24 years for a large surface coal mining company in Canada, eventually becoming manager of engineering. He has published six books on heavy equipment, but considers this book his crowning achievement, calling it the most comprehensive book ever written about earthmoving equipment. I’m not about to argue otherwise.

As much as I liked this book, it does have one glaring problem. The photos inside the book are gray and fuzzy-looking. Instead of getting sharp and colorful pictures like those on the front and back covers of the book, the reader is left with murky views of the equipment. This problem, I’m guessing, may be due to most of the photos being in color originally. When a color photo is changed from color to black and white, the details within the photo can be easily lost. This grayed-out effect made it difficult for me to see all but the most obvious attributes of the pictured equipment. Hydraulic lines and cylinder placement became hard to follow, and trying to trace how cable-operated equipment was rigged was hopeless. The price of this book is very, very low given its size and scope. To do the whole book in color might increase the price to the point where no one would buy it. If that’s the case, then gray photos are better than no photos, but, darn! High-definition color photos would have made this book so much better!

I also have a few petty grumbles about the dull typestyle used in the picture captions, and the appearance here and there of typographical errors. Neither of these distractions do any serious damage to the reader’s ability to understand the data being presented. The page design is repetitive with an unimaginative industrial layout. Luckily, the information contained in this book overrides the lack of creative page design. This book was obviously meant to inform more than entertain.

The book opens with Acknowledgements, then an Introduction followed by 17 chapters. After an initial chapter dealing with the development of early earthmoving machinery, each of the next 16 chapters covers the historical development of a specific type of mechanized equipment, with the photos arranged alphabetically by manufacturer. From Loader-Backhoes to Walking Draglines, it’s all here. A short Bibliography, then an Index listing the equipment discussed and pictured in the book, close things out.

Copyright 2015, Bill Ingalls (SpeedReaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter