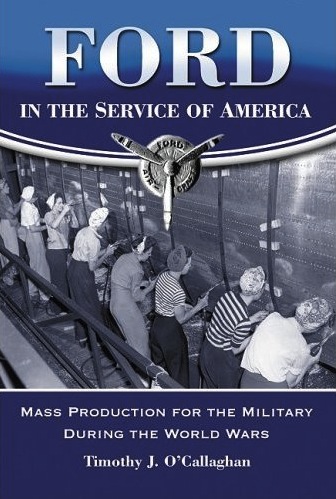

Ford in the Service of America: Mass Production for the Military during the World Wars

by Timothy J. O’Callaghan

by Timothy J. O’Callaghan

World War Two now lies approximately two-thirds of a century in the past. It must be incomprehensible to those not alive then, that there was a time when virtually all the resources of our domestic life were directed towards a single goal; victory over clearly identified enemies.

Preparedness for the eventual conflict began slowly in 1940. There was fear even before Pearl Harbor of a German air attack from hidden bases in countries south of the US and from enemy planes operating from aircraft carriers off the coastlines. Even though Henry Ford was anti-war (after all, there were Ford plants and facilities in England, Germany, and seven other European countries under Hitler’s control), he became fully engaged in rearming for national defense. The story of the Ford Motor Company’s contributions to the war effort 1940-45 is the theme of Ford in the Service of America.

O’Callaghan’s story is factual and straight-forward: what the products were; how they were developed, refined and manufactured; and their number and cost. What could have been a stultifying array of facts takes on a life of its own and cumulatively become “the story”. To the extent there is a hero, it must be Charles E Sorenson, whom Henry Ford designated as the chief of war production (and who became another casualty of Harry Bennett in 1944).

Take the B-24 Liberator bomber and its Willow Run assembly plant as the best examples of Ford at war. Consolidated Aircraft Corporation developed the B-24, but it was not thoroughly tested nor production-engineered when Ford undertook its mass production. To convert Consolidated’s hand-assembly to an assembly line, Ford sent 200 engineers and production men to the factory in San Diego for four months to make an up-to-date set of plans. Thirty thousand drawings were re-made for the first Ford-built B-24. From then on, O’Callaghan records “only another 10,000 drawings were required to cover changes for the next 490 bombers built to the introduction of the B-24H model, and only 20,000 more drawings were required to the end of production.”

Then there were the drawings required to break down production tasks to their simplest in order to develop each worker’s individual assignment. The reader has a mental picture of sleepless nights as these changes must have been priorities. Surely, the engineers and production men should be regarded as silent heroes on the home front, sacrificing for the war effort.

Overall, each B-24 contained a total of 465,472 parts and rivets. Workers to assemble them had to be found, hired, housed, and trained. At the peak, 43,369 were employed at Willow Run, 39 percent of them women. Willow Run was built on land largely owned by Henry Ford for soybean farming. The plant enclosed almost 4 ¾ million square feet of floor space and an assembly line over a mile long.

Ford’s second best-known wartime product was the ubiquitous jeep. But did you know that there was an amphibious version called the Seep? Gliders, tanks, and squad tents were some of the other materiel produced. And, as the author notes, Ford wasn’t the largest producer for the war effort.

Flawed with anti-Semitism and, in many ways, a narrow mind, Henry Ford was nonetheless a believer in diversity. By 1914 it was company policy to find jobs for the blind, deaf, and amputees, both civilian and veterans, and by World War Two, nearly half of the blacks working in the Detroit auto industry were employed by Ford.

The genesis of the book is noteworthy. In the early days of the war, Henry Ford asked Charles LaCroix, the assistant director of Greenfield Village, to write Ford’s history of the war, but Henry died before the work was published. LaCroix’s eight volumes summarizing the contents of 42 archival boxes have been available to researchers but this is the first work dedicated specifically to this area of Ford’s history. These archives were the primary research tool for O’Callaghan, now 79, who served in Ford in management for 40 years. His personal recollections of the war are bound to be poignant as he dedicates the book to the memory of his brother, killed in Okinawa when the author was only 15.

This is a commendable book. When I received it for review, my first thoughts were that it was of little personal interest and I should pass it on. But the more I browsed, the more interesting and significant it became, and I soon was immersed from cover to cover. It has its share of typos (some unforgivable such as Lindburgh) but not enough to question the accuracy of what O’Callaghan reports.

Copyright 2010 (speedreaders.info) Reprinted with permission from SAH Journal 243, January/February 2010 of the Society of Automotive Historians and author/reviewer Taylor Vinson.

(Reviewer Vinson is past president of the Society of Automotive Historians as well as past editor of the SAH Journal. An erudite and learned man, he was born in 1933 and died October 2009. This review was published posthumously.)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

A very accurate account of my book