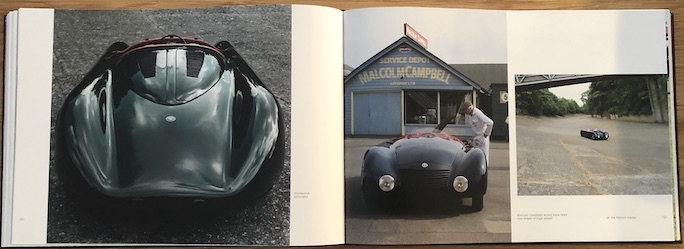

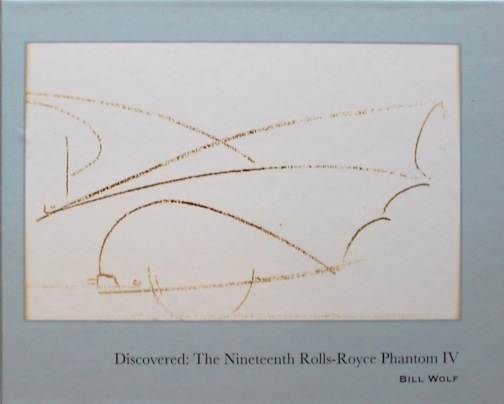

Alfa Romeo Aerospider

by Georg Gebhard

“By definition a concept car has to offer a glimpse into the future and to demonstrate what can be made possible. By its appearance the Aerospider would have been the fist concept car, but it also was designed to drive and still does.

This Alfa Romeo had the potential of pointing the development route of car design, but failed as it was always hidden in its early life.”

Fantastic car, fantastic book. There’s only one of the former and 500 of the latter so there’s a pretty good chance you’ll not get to clap your eyes on either without making an effort.

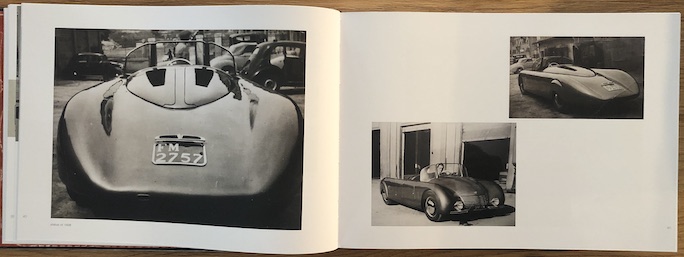

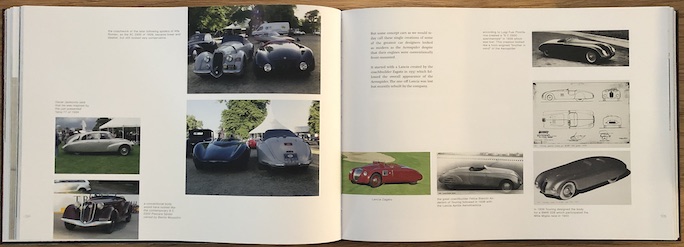

Not all of the car’s many owners over the eight decades of its existence treasured it, and it’s only thanks to the current one that chassis 700315 is restored to its full splendor and making the rounds of the worldwide concurs scene.

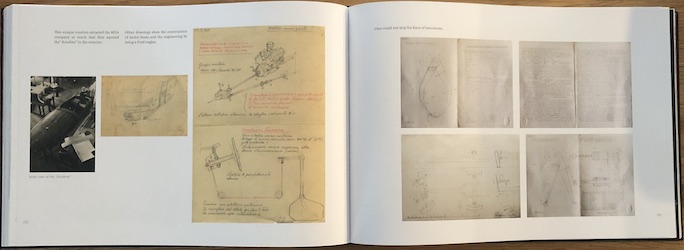

Before delving into the book, an issue needs to be dispensed with: digital denizens with a long memory, especially any Alfisti among them, will recognize this car—and recall that some 15 years ago there was hardly an internet forum that didn’t have something to say about its provenance and legitimacy, usually critical and at best, skeptical. The reason to mention this at all is to make two points. 1, a little knowledge is a dangerous thing; 2, once something is on the Almighty Interweb, it never dies. Meaning, even today readers will come across all that outdated and often untempered commentary and not realize that the world has moved on. This book, written by the fellow who owns the car and had it restored and has poured years into researching it, rounds out the record with all that is factual and documented. Not least, it introduces into the record original materials from the constructors, courtesy of the son of one of them and who wrote one of the Forewords.

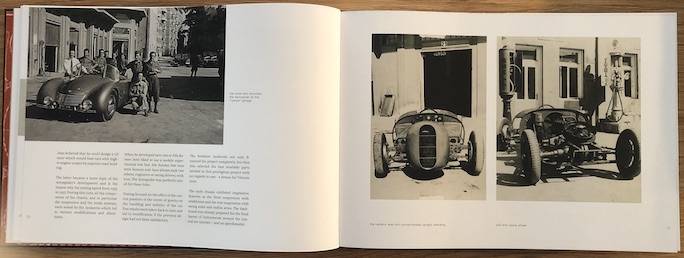

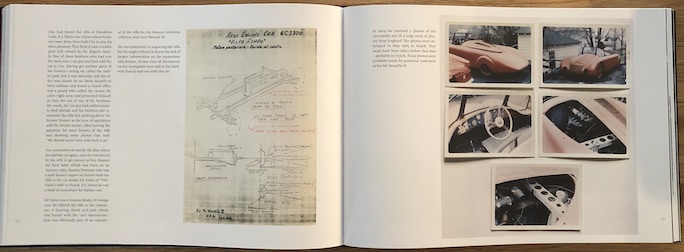

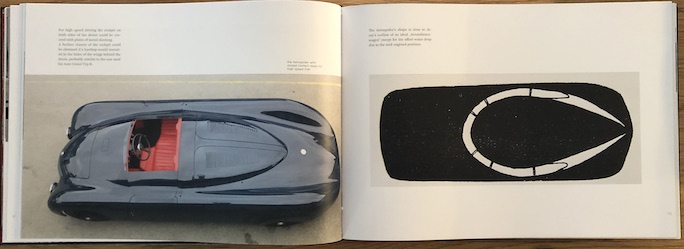

German Porsche whisperer Alois Ruf, in the other Foreword, describes this one-off Alfa as “the perfect execution of a bunch of ‘crazy’ ideas.” Initially conceived as a high-speed—as in 400 km/h—12- or 16-cylinder competitor to Mercedes and Audi race cars the Alfa had as much to do with upholding national honor as with engineering in and of itself. One would think Alfa Romeo would put all its resources behind something Mussolini himself had declared a priority. Instead it was so much a secret project that Alfa’s chief engineer Vittorio Jano had to work with outside resources to whom he would provide parts and expertise, which came to a sudden end when Alfa let him go in 1937. The whole project then took a turn into an entirely different direction as a 6-cylinder road car with three-across seating, mainly so that its constructors could recoup their money. It moved from Italy to the US, then England, the US again, and back to Europe and after multiple owners in different countries, into the hands of something called the CG Foundation in Germany (in 2007), its initials representing the names of the car owner and his wife.

All of the above hints at a diverse and intriguing history, and means posterity will be clamoring for a book to put everything in its proper place and paint a full picture. No longer do you have to make do with the odd photo that used to appear over the years in magazines with the question “What is it?” or speculation whether this was merely a rogue Special with a doctored history. An amusing aside, I have before me an ad from the Nov. 1970 issue of Road & Track advertising a “Unique Alfa Romeo, circa 1934. Center steering, 3-seater, open sports. Mid-engine.” that describes it as a “guilt-edged investment for collectors or museum.” Surely a Freudian slip: it should have been gilt.

While the car was never “lost” (in the sense of being unaccounted for) it was certainly not always recognized for what it actually was. The one person who could have set the record straight, Jano, kept no written records and died in 1965, but Luigi Fusi who had worked with him attempted twice to acquire the car for the Alfa Romeo Museum.

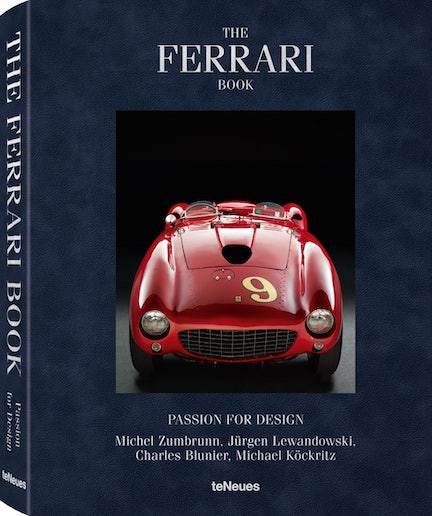

Bristling with splendid Michael Zumbrunn and Michael Furman studio photography and an impressive hoard of period illustrations the landscape-format book introduces the car in the context of other aerodynamic projects of its time and lays out the Aerospider’s specific performance goals and technical features. The coverage is not always at the level of magnification one would wish for, or that researchers in the future would wholly benefit from. For instance, Gebhard does not relate in any detail the origins of his interest in the car, how the acquisition came about, or the restoration. Also, it must be said that the story skips around quite a lot, or, rather, skips over certain bits. Absent an Index it is not easy to put the disparate pieces together. On that score it must also be said that this is probably the result of the book being self-published, i.e. without the guiding hand of an editor who could have kept the macro and the micro strands better organized. This lack of structure is also evident in continuity errors such as chapter titles called one thing on the Table of Contents but another on the actual page, never enough to cause real confusion (there is one chapter that starts on a different page altogether) but certainly unorthodox and really not productive.

The one thing that can cause confusion is the English text, clearly not the work of a native speaker. This ranges from the just slightly off-sounding (reread, for example, the introductory quote above) to serious head-scratchers such as: “Alfa Romeo’s abilities which were mainly based on their superb drivers like Tazio Nuvolari flared only.” It takes imagination to figure out that the author means to say that Alfa had only limited success unless they had good drivers. Almost all of such snafus would have been easily avoided by taking more time or paying for experts. No matter, thanks to Gebhard the envelope has now been expanded in a meaningful way.

Copyright 2021, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter