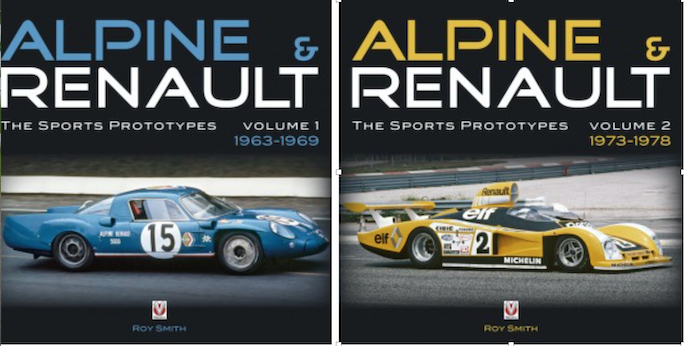

Alpine & Renault, The Sports Prototypes Vols 1 & 2

by Roy Smith

Following his previous book Alpine & Renault: The Development of the Revolutionary Turbo F1 Car 1968–1979, Smith takes a look at a very different animal by the same maker/s in this two-volume set: the Sports Prototypes from 1963–1978. Good-looking, reliable, beloved by the French, successful even, but compared to other cars of the time not a whole lot has been written about these Alpines, certainly not in book form and most certainly not in English. Moreover, the full chassis and race history of the M63, M63B, M64, M65, A210, A211, A220, and A221 sports prototypes had never been recorded completely in any language. This, aside from Smith’s personal decades-old interest in these models and in motorsports in general, is a primary reason why he took it upon himself to put pen to paper after having retired from a professional life in sales and marketing.

Although no stranger to the subject—having written magazine articles about Alpine Renaults since 1989 and being the UK correspondent for the French magazines Rétro Passion and Mille Miles—Smith finds himself saying: “I never really wanted to be a detective!” Famous last words . . . and in this book the very first words in the author’s Introduction. He went about his sleuthing the right way, by seeking out and personally interviewing a good number of the now 70- and 80-year-old former company and racing team members as well as people associated with the Alpine program such as ex-Lotus chassis designer Len Terry. And no fewer than nine people wrote individual Forewords, all praising this three-year research effort and its contribution to motorsports history. The result is a 150,000-word in-depth treatment that examines the pre-history (i.e. the brothers Renault, and father and son Rédélé who founded Alpine) and the Alpine models’ development, testing, specs, and competition history in Europe, the Americas, and the Far East. It covers every chassis and nearly every driver. There is a natural breaking point between the two books; volume 1 ends with Renault withdrawing from sports prototype racing in 1969 and volume 2 picks up the thread four eventful years later during which Renault had taken a majority stake in Alpine (they didn’t fully absorb it until 1977), totally reconfigured the cars to conform to the drastically changing sporting regs, and embarked on a failure-not-acceptable mission to score an overall win at Le Mans. So, while each volume covers a distinct period and stands on its own, the only way to get the full picture is to have both.

Incidentally, one name is integral to this story, especially the first part: Amédée Gordini, racecar driver and sports car manufacturer who supplied engines to Alpine. He will be the subject of Smith’s next book, due late 2011. Women in racing are rare enough, certainly back then, and female readers/racers especially will appreciate photos and text about Lella Lombardi and Marie-Claude Beaumont.

The over 600 photos, coming from a large number of sources including company archives and private collections, cover every conceivable aspect and include such gems as styling bucks, clay models, and workshops. The captions are often a bit sparse. There are several whole-car cutaways and track maps, detail shots of components and assemblies, function diagrams, memos, and peripheral bits such as race posters and programs and even a diagram (in English) of personnel and tool placement in a pit box. Of note, vol. 2 was able to draw on data in an internal Renault Sport dossier that is privately held. In a word: thorough.

Appended to each book are detailed race results for works cars during the respective years. Vol. 1 contains an additional list of results for Le Mans test weekends whereas vol. 2 ends with closing remarks about Renault Sport activities at Indianapolis and Bonneville. Each volume has two different b/w cutaway drawings of cars on the front- and endpapers.

A note about the Index: several entries, especially of proper names, give no page references but are followed by the notation passim. Especially in this day and age it is probably wildly optimistic to assume that the reader will know this to mean “to be found at many places in the same book” (from the Latin passus = scattered, in the sense of “here and there, everywhere”). In other words, there are too many references throughout the book to these specific entries to enumerate individually.

A very accomplished effort. If only everybody spent their retirement years this productively!

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

Alpine & Renault – The Sports Prototypes

by Roy Smith

Veloce Publishing Ltd., 2010

Volume 1: 1963–1969

208 pages, 300 color & b/w illustrations

List Price: $69.95 / £34.99

ISBN-13: 978-1-84584-191-1

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter