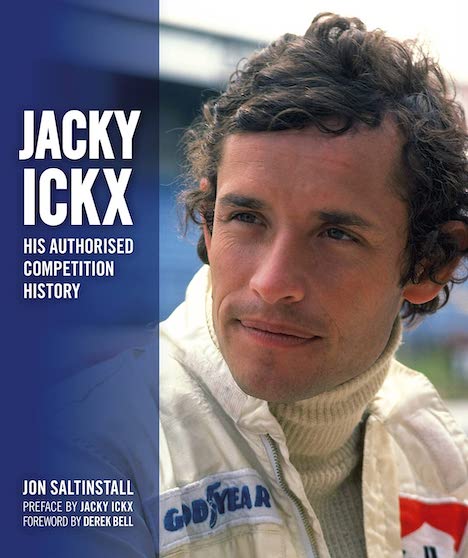

Jacky Ickx: His Authorised Competition History

by Jon Saltinstall

by Jon Saltinstall

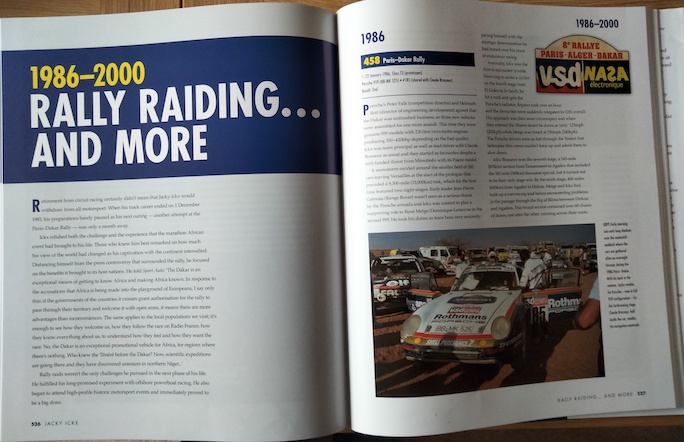

“As far as I’m concerned, Africa is the most interesting part of my life. The landscape, the setting . . . it cuts you down to size. Africa opens your eyes.”

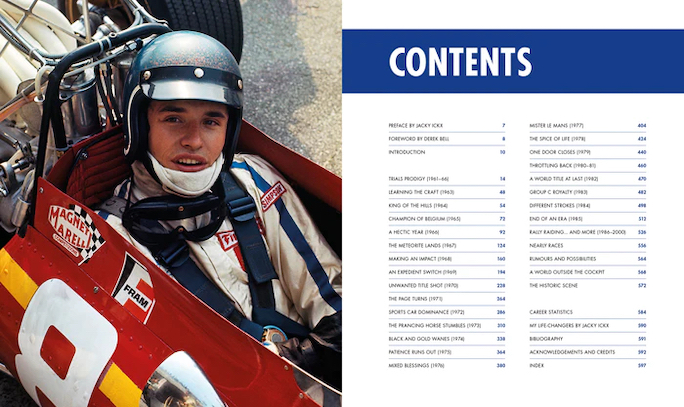

If you were thinking about writing a Jacky Ickx biography, I am the bearer of bad news. The breadth and depth of Jon Saltinstall’s huge (608 pages, ca 7 lb) book means that there can be very little left to be said about its subject. The good news for the rest of us is that the author’s diligence and resourcefulness has resulted in a book that not only gives a precis of each of the 573 events Ickx contested, but also lists the races he didn’t start and—get this—even details the “rumours and possibilities” that never materialized.

Saltinstall already has form—his 2019 book on Niki Lauda’s career also covered every event in which its subject competed—but the Ickx book is almost twice as big. That fact tells you more about Ickx than it does the author, because Ickx’s career was both long (1961–2000) and involved an extraordinary diversity of machinery and venues, from Ferrari Formula One cars to rally raid Lada Nivas, and from Daytona to Dakar.

My first recollection of Ickx (b. 1945) was Autocar’s report of his astonishing performance in the 1967 German Grand Prix, when he qualified his 1.6L Formula 2 Brabham third, in front of Formula 1 cars from teams including Ferrari, BRM and Eagle-Weslake. Saltinstall recounts how “Jackie Stewart was even spotted rushing over to the Matra pit to ask Ken Tyrrell to tell his young driver to slow down, ostensibly for his own safety.” Obviously, Stewart’s concern didn’t relate to the fact that the young Belgian upstart had just had the temerity to outqualify him . . .. Ickx might have looked as though he had walked off the set of a Nouvelle Vague film but drives like this made his talent seem otherworldly. But Ickx’s career arc was also an enigma, and this book helped me answer the question that has haunted me since I saw him drive his ageing Lotus 72 to his last Formula 1 victory, at a soaking Brands Hatch in 1974. Was I watching the last triumph of a nearly man, a driver who had once seemed invincible? Was Ickx now beginning to struggle to survive at the rarefied altitude that only the true greats inhabit? This book helped me understand that the Formula 1 driver who had once wanted to be a gamekeeper or gardener was unique, with a persona profoundly different to the typical racing driver.

The book follows the Lauda book’s template by providing a year-by-year summary of every event in which Ickx competed, with a short introduction and conclusion for each season. There is also reference to test sessions and other relevant events. The book contains over 900 images, which are mostly in quarter page, or smaller format. This level of detail means that many readers may be tempted to read only accounts of those seasons that interest them the most, while only skimming or ignoring the rest. Don’t give in to this temptation, because if you want to understand this enigmatic driver, this book should be read from cover to cover. That way you will begin to understand how 1961’s motorcycle trials prodigy became a professional racing driver within four years, and then burst on to the international scene shortly afterwards. But what a four years it had been—the author’s research enables the reader to appreciate how Ickx relished every discipline, and mastered them all without apparent effort. There were trials, speed hill climbs (far more important then than now), races and rallies in machinery as varied as Ford Mustang and Cortina, Hillman Imp, BMW 700S and Mini Cooper S, as well as his trials bike of choice, the Zündapp.

The 1967 chapter is entitled “The Meteorite Lands” and it’s an apt description of the impact Ickx made that year. He wasn’t the proverbial “coming man” anymore but a property so hot that he showed every sign of becoming The Man. And over the next few seasons he did just that, with his only real rivals in his early F1 career being Stewart and Rindt and arguably belonging to a class of one in sports car racing; remember Le Mans 1969?

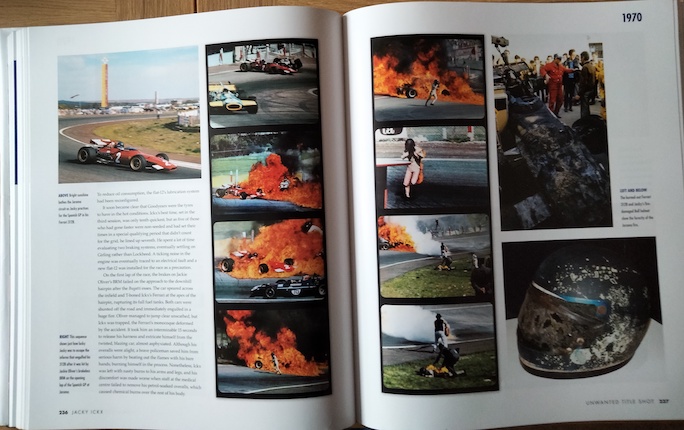

And it is that race that is almost a microcosm of Ickx’s career. His blinding, sustained speed was almost a given by then, but there was something else as well. Remember how “he walked slowly and deliberately to his GT40, climbed in and fastened his safety harness . . .” before setting off at the back of the field? It was rebellious, iconoclastic, almost a thumbing of the nose at one of the sacred traditions of Les Vingt Quatre Heures Du Mans. It was the same stroppiness which led to his boycotting of the GPDA and walking away from Ferrari in 1969, because “his overriding consideration had been the freedom to continue racing sports prototypes for the . . . JW Automotive Engineering squad.” But this was also the man who sent a handwritten thank you letter to each Ligier mechanic after his miserable performance in the 1979 Canadian Grand Prix. All great race drivers are their own men but, even judged against his peers, Ickx was exceptional in his individualism. Which made it all the more remarkable that the second and third chapters of his career were in disciplines that demanded compromise and teamwork.

Ickx’s tally of eight Great Prix wins might be eight more than most F1 drivers ever manage, but it seems absurd that the likes of good but not brilliant drivers like David Coulthard and Valtteri Bottas have more wins. It is also extraordinary to be reminded by the author that Ickx drove for no fewer than eight separate F1 teams—eight!—and I bet I’m not the only reader who had forgotten that. Ickx drove plenty of sports cars too, but the second chapter of his career was almost exclusively Porsche. If you are my age, if you hear Ickx’s name you’ll probably visualize a blue-helmeted driver leading a Grand Prix in a Ferrari, but if you’re under sixty you’ll likely see a Rothmans-liveried Porsche 956, heading imperiously to yet another endurance race victory. The 1969 Le Mans win was supplemented by another five, four of them in Porsches and one in a Gulf Mirage. And even when Ickx didn’t win, the author reminds us what failure looked like—the crisp summary of Le Mans in 1983 reads “Porsche 956 (005) #1 (shared with Derek Bell) Qualifying 1st Result 2nd (fastest lap).”

The third and final chapter of Ickx’s career saw a complete change of direction. There were to be no more Grand Prix sprints, no more 12 or 24 hour races, but rally raids to Dakar, Egypt, Morocco and beyond. More success was to come, but there was rivalry and tragedy too. Ari Vatanen is almost beatified in rallying circles, so reading about his desperate attempts to overtake Ickx in the 1989 Paris-Dakar came as a surprise. Two years later, Ickx’s close friend and co-driver Christian Tarin died after their Citroën ZX crashed on The Rally of The Pharaohs. Ickx was distraught: “It was the worst thing that happened to me in my whole life. You never recover from that. Really, never.”

Ickx retired in 2000 but he has remained active on the historic scene and is celebrated as one of the few survivors of 1960s Grand Prix racing. To suggest this book is a comprehensive account of his competition career is to do it an injustice because it is a tour de force. The caption of one photograph serves to illustrate just how diligent Jon Saltinstall has been. It depicts a pit stop for Ferrari 312PB chassis #0888, and it took place nearly 51 years before the book was published: every single person in that picture, from Firestone tire technician to engineer/aerodynamicist and team refueller is identified by name.

Saltinstall’s Lauda book raised the bar for this type of biography; this book raises it higher still, and it is fitting that it is about the driver whose personality was so unlike those of his peers—just re-read the opening quotation.

Copyright 2022, John Aston Speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter