The Lexington Automobile, A Complete History

by Richard A. Stanley

by Richard A. Stanley

This hardcover book displays a nice balance between photos and text, making for a pleasing graphic look. However, the history of the Lexington car company is told too dispassionately for my taste, reminding me of Dragnet’s Sergeant Friday as he requests of a gossipy witness, “Just the facts, Ma’am.” Hiding below the surface of the text is what appears to be an intriguing story of financial wheeling and dealing, a corporate double cross or two, multiple production manager firings and hirings, nepotism gone wrong, and more.

Unfortunately for the reader, none of these hints at corporate shenanigans are pursued beyond the level of what a small town newspaper would write about a major local company, leaving any unpleasant awkwardness to remain unspoken.

Lexington cars were an assembled product produced in Lexington, Kentucky (1908–1910) and Connersville, Indiana (1910–1927). During that time the company collapsed financially three times in 1912, 1923 and 1926, staying alive only by refinancing itself with new cash and investors. The up and down story is told primarily through background data gleaned from articles in approximately 350 local newspapers and national automotive industry magazines. While the events, names and dates are profuse, the heart of the story is a bit vague as the author avoids drawing conclusions, leaving readers to draw their own based on “clues as to why finances were what they were.” To this reader, the clues would seem to say that Lexington was founded by true believers in Kentucky interested in racing who wound up being milked to death by Indiana wheeler-dealers more interested in industrial expansion.

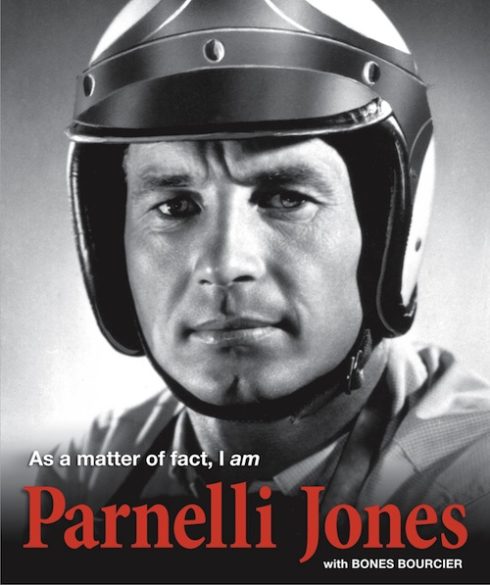

Toward the end of the Lexington saga Billy Durant, original founder of General Motors, got involved by contracting to use Ansted engines in his Durant and Princeton automobiles. The United States Automotive Corporation, apparently a financial structure created by the Ansted family to capture new funding to continue Lexington production, used the six-cylinder Ansted engine in Lexington cars and hoped to generate economies of scale by selling thousands of engines to Durant. Unfortunately, everything fell apart for both the Ansted’s United States Automotive Corporation and Durant Motors as the slowing national economy reduced car sales at the end of the 1920s. The Ansted family, however, survived the Lexington failure, leaving Connerville for California and Indianapolis, Indiana. Ansted’s son William Jr. eventually become an Indy car owner, winning the Indy 500 in 1964 and 1967 with A.J. Foyt driving.

The Lexington story is an interesting one from an industrial and historical viewpoint. How did car companies, like Lexington, get started, and why did they fail? The immediate answer for failure in Lexington’s case seems lack of production volume, yet other small-volume car companies of the time—Packard, Stutz, Mercer, Duesenberg and others—survived and thrived by finding a niche for themselves in the marketplace. Lexington, however, apparently had weak management that lacked a clear vision of what it wanted the company to be. The original company founders and engineer John C. Moore wanted to go racing, entering the brutal 1909 and 1910 multi-thousand mile Glidden endurance tours, and the 1912 Indianapolis 500. The company’s racing high point came when Lexington won the Pikes Peak race in Colorado in 1920, 1921 and 1924, retiring the prestigious Penrose trophy with their third victory. Lexington management, however, was unable to translate the string of Pikes Peak wins into meaningful sales. Exactly what the car was meant to represent to the public was never established. Was it an expensive prestige car like Packard, a performance car like Stutz, or a solidly built and reliable vehicle for everyman with better than average fuel economy and speed? The book never makes that clear, reflecting, perhaps, the basic marketing problem Lexington management was never able to solve. While the Lexington car, with dual exhausts and other “performance” alterations seemed to be designed mechanically for endurance, hill climbing, and top speed the exterior body styles reflected a more conservative and stodgy look not at all in keeping with the dynamic power-stance body designs of other high-performance cars of the day.

The book has lots of photos and is well written but lacks the “pop” that would make it great. All the data is there, but it left me wondering at the end what it was all about. The author, a member of the Antique Automobile Club of America and the Society of Automobile Historians, is curator of the Fayette County Historical Museum in Connersville where the Lexington was built (he is also a retired Connersville Junior High South school administrator and teacher). Perhaps this makes the subject a bit too close to home to approach it with clinical detachment? The book is quiet when it could have been loud. History does need to be factual, but it can also be openly speculative, insightful, and adventuresome—without offending sensibilities.

Beyond noting that in interviews old employees call “management [was] top-heavy” and Frank Ansted “quite an operator,” nothing is said that might offend an idealized version of the past beyond the mention of “several theories”—which are then not expounded. This lily-white polite presentation weakens the overall quality of the book, which is a good, solid, data-filled historical retelling of the Lexington saga, and a book worth owning. While it is a good book, it is not the great book it might have been with a little more critical investigative reporting.

The book opens with a memoriam to the author’s late brother Marvin who helped obtain the materials for it, followed by Acknowledgments, a Table of Contents, Preface, nine Chapters, an Appendix of Lexington models, an oddly set-up chapter Notes section, a Bibliography and a frustratingly weak Index.

Copyright 2012, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter