Lightning Eject: The Dubious Safety Record of Britain’s Only Supersonic Fighter

“During a period in the early 1970s the attrition rate was the loss of a Lightning every month. There was a six per cent chance of a pilot experiencing an engine fire during a typical tour and a one in four chance that he would not survive.”

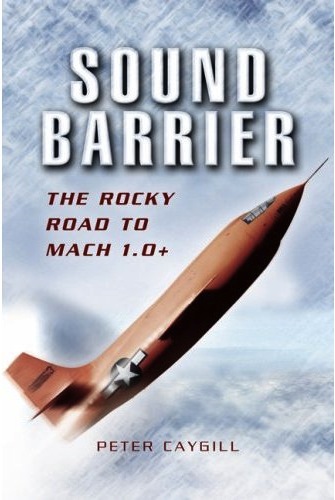

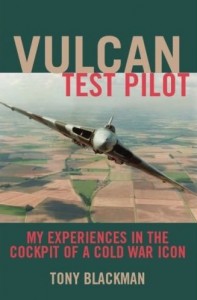

Britain’s English Electric Lightning (1959–1988) was not the only aircraft combining great potential and a very iffy safety record; you only have to think of another superplane of that time, the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter; there’s a reason it was called The Widowmaker. . . . Over fifty of more than 330 Lightnings made were lost—to aerodynamic overloading, canopy separation, engine fire, hydraulic failure—but still pilots were standing in line to strap on the “skyrocket.”

Caygill is an eminently competent aviation writer with a number of important books to his credit, including another Lightning book for the same publisher, 2006’s Lightning From the Cockpit (ISBN 9781844153558). No matter what the title says, he’d be the first to know that this single-seat interceptor fighter is not “Britain’s only” one in service but rather the only British-designed one. A detail, but an important one. This is why you have an editor—except in this case it was the editor who introduced this snafu, rewriting Caygill’s original title and making other changes without telling the author. And unlike Caygill, he is not a pilot and so didn’t think anything of changing a pitot head to a pilot head. Off with his head, don’t you think?

The Lightning was aptly named: it was fast and could climb almost vertically, reaching 36,000 ft—about half of its observed but never disclosed maximum ceiling—in less than three minutes. (An F3 reached 88,000 feet!) While this looks cool it is not the quickest way to gain altitude but it made the Lightning an impressive airshow performer. It is, in fact, one of the highest-performance aircraft ever used in aerobatics. Quick bursts of speed are one thing but what set the Lighning apart was its capability for sustained speed without using afterburners (reheat) which are inefficient and have other disadvantages in prolonged use. This is called supercruise and the P.1 prototype was the first to ever achieve it. The approx. Mach 1.2 it achieved in 1954 look positively slow today but back then it was the outer edge of the envelope.

As with most things technological, pushing the envelope has its price and requires trade-offs. Whether car or plane, speed and acceleration are no friend of weight-hogging rigidity or storage. The Lightning’s particular set of compromises caused a particular set of failures. Still, in 2008, long after it was withdrawn from active service the Lightning earned the Engineering Heritage Award bestowed by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers for “landmarks of significant engineering importance which have changed or enhanced the way we live.” Long story short, the Lightning is an important plane but its importance came at a cost—hence this book.

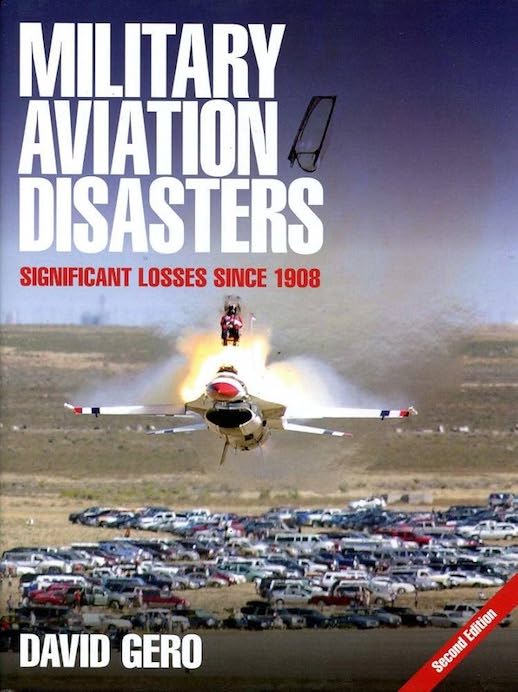

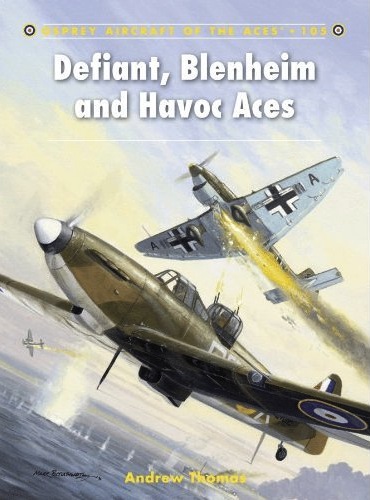

Many books have been written about this aircraft. Once again Caygill demonstrates an enviable sense for pace and the proper place for everything; it is an enjoyable book to read. What he adds to the record is a look at the difficulties engineering and flying the machine. After you’ve finished just the first chapter’s twelve pages you will be overcome by a sobering awareness of just how difficult this was. The photo shown here is not among the 48 shots used in the book but illustrates the drama perfectly. Only RAF service is examined, not Saudi Arabian.

The story unfolds chronologically and draws on accident reports, Board of Inquiry findings, and firsthand accounts from pilots. This means a certain amount of pilot speak and technical jargon (there is a Glossary) is inevitable but it is not so prevalent as to disrupt the general-interest reader’s ability to follow the story. Naturally, an understanding of aircraft behavior and flight controls add to the impact. It should also be said that while accidents are the main aspect of this book, this is not a morbid wallowing in gory details or wringing of hands but simply another, and inevitable, side of engineering by trial and error. Caygill, for instance, shows singular restraint in his photo choices. Most aircraft are shown on the tarmac, intact. In fact, the truly engineering-minded reader concerned with the inner workings of things will find this approach all too sterile and unenlightening. There are no technical drawings or diagrams and even simple things require of the reader an ability to construct details in his mind (examples: the position of an arresting cable at the end of a runway being at just the height to shred the Lightning’s fuselage; time and space relationships when, say, a strike to A causes B to buckle and C to jam and D to break off).

Similarities to the aforementioned Starfighter’s safety record and mission profile are considered in a final chapter. Statisticians—and actuaries—will find much to ponder here: is there a hotspot for accident rates during a life cycle and what is it related to?

The book closes with a remembrance of the 14 fatalities and a Glossary. Appended are an explanation of RAF Damage Categories, a chronology of Lighnting losses, and an excerpt of Emergency Drills from the Pilot’s Notes. The Index is divided into proper names and aircraft serial numbers.

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter