The Life and Times of Henry Edmunds

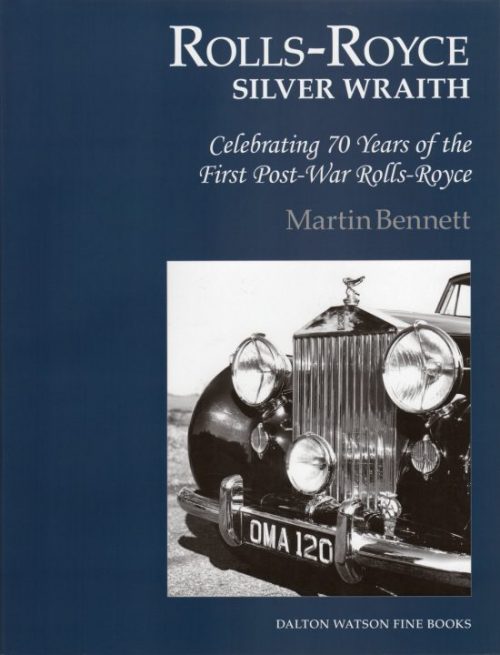

Originally published in 1993 as a hardcover, this important book probably would have had a much firmer hold on life if it had been under the care of the present publisher right from the start, as opposed to Academy Books which poorly promoted it and then went bankrupt. In the context of the 2004 centenary of the Rolls-Royce company, the RRHT decided to reissue this book, by then long out of print (along with RRHT Chairman Emeritus Mike Evans’ important related book Manchester Origins) so as to properly record the new discoveries that had been made since their original releases and introduce a new generation of readers to the early history of Rolls-Royce.

Initially, the revised edition consisted of small corrections made within the original text, but much like the 1st edition was almost held up because of 11th-hour discoveries (a trunk full of personal effects of Henry Edmunds’ second wife, found unopened after 64 years, containing, among other things an almost complete manuscript of Edmunds’ memoirs), so this 2nd edition was impacted by late-breaking new information—and of the highest order. It must be remembered that even at the time of the 2004 celebrations of the company’s founding, there existed no hard evidence that Royce and Rolls did, in fact, have their momentous first meeting on the day all the world celebrates: May 4, 1904. It was all conjecture, circumstantial evidence—and even that dates back to only the 1970s when the date of the meeting was fixed, plausibly, for the first time.

Just as the 2nd edition was being finalized, news broke—a few weeks after the official celebrations—that an actual artefact, of unimpeachable provenance, had surfaced and validated the date (an engraved lighter given by Charles Rolls to Henry Royce). This story is appended here. But there is newer news still, which didn’t make it into the book: Edmunds’ backing of a project for BMR Gearless Cars in 1920–21.

To the hasty eye, Edmunds may appear peripheral in the history of Rolls-Royce; he is anything but. And, beyond that, he deserves to be known for so much more. He pioneered electrical lighting, traction, and telephony; was a confidant, friend even, of the great inventors of his day; promoted the Phonograph and the Graphophone; held 150 patents and was, of course, an automobilist of the first hour. All this is explained here, in grand detail—not just Edmunds’ life but his era, a time of unprecedented, tumultuous inventions.

In his Postscripts, Tritton, a newspaper man by trade, reveals a few of the trials and tribulations the biographer encounters in reconstructing his subject. (No index)

Copyright 2013, Tom Clarke/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter