Rolls-Royce Motor Cars

Haven’t been to Rolls-Royce’s Goodwood headquarters lately? Let this book take you! Actually, it’ll show you quite a bit more than you’d ever see on your own, partly because of the unlimited access Rolls-Royce gave the photographer and partly—make that largely—because of the way he sees the world.

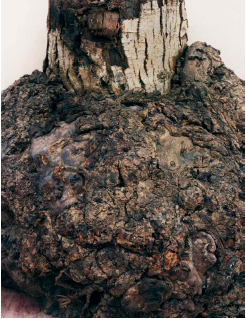

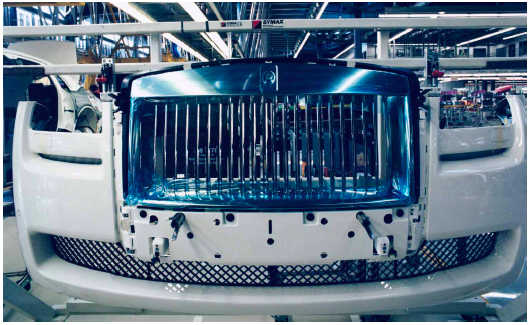

Nothing about this book is straightforward . . . it contains no text whatsoever except for the Impressum. It doesn’t explain whose idea it was, what it is about, whom it wants to reach. Not even who the photographer is. In many ways it is like the Rolls-Royce car—if you don’t “get” it you shouldn’t have one. If this sounds harsh, it isn’t meant that way but clearly both the book and the cars exist on the premise that those who know, know, and those who don’t may be left to go their merry, ignorant ways. Consider the first image in the book, a full-page close-up of . . . tree bark.  Only people who know about book-matched veneers in bespoke cars, and only certain makes at that, will recognize what they’re being shown and know what its relevance is. It’s not until a dozen pages of similar material later that something recognizable as a Rolls-Royce is shown in the form of an unmarked grille shell and front clip.

Only people who know about book-matched veneers in bespoke cars, and only certain makes at that, will recognize what they’re being shown and know what its relevance is. It’s not until a dozen pages of similar material later that something recognizable as a Rolls-Royce is shown in the form of an unmarked grille shell and front clip.

“Worldly” readers will find a clue to the book already in the name of the photographer. Bolofo is a marquee name in the world of fashion and art photography, the latter used in the sense of “photography as art” rather than photographing fine art although this distinction has its limits because Bolofo, South African and self-taught, clearly treats what he has in front of the lens as art.

You’ll find his work in any number of splashy fashion magazines and advertising campaigns from Hermès and Dom Perignon to Banana Republic and Avon. He’s also done a number of short films and, more relevant to this Rolls-Royce book, photo studies of the Margaret Howell shirt factory in London or renowned Bugatti restorers Dutton Ltd. Years ago he said in an interview: “. . . I do not photograph any subjects immediately; I visit them and grow as a friend. If I miss a great moment, it will come again. I trust the patterns of a person. I approach objects the same way. I love the expression ‘still life’—it may be still, but it has life.” That last sentence is a key to his work here.

“. . . I do not photograph any subjects immediately; I visit them and grow as a friend. If I miss a great moment, it will come again. I trust the patterns of a person. I approach objects the same way. I love the expression ‘still life’—it may be still, but it has life.” That last sentence is a key to his work here.

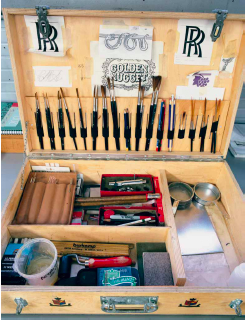

The press release calls the book a “visual diary.” It shows various aspects of assembly on the Phantom and Ghost lines, artisans in several departments, and architectural features of the Goodwood plant. The sequence of the photos does not in any way follow the actual production process,  nor is the photo selection representative of the totality or relative importance of the steps required to put a car together. For instance, some 22 pages show the making of the iconic Spirit of Ecstasy mascot, 19 of them sequential and the others scattered about.

nor is the photo selection representative of the totality or relative importance of the steps required to put a car together. For instance, some 22 pages show the making of the iconic Spirit of Ecstasy mascot, 19 of them sequential and the others scattered about.  The only reason to point this out is to impress upon the reader to throw out preconceived notions about that this sort of book “should” contain. Bins of hose clamps and trays of yarn are shown with the same sense of curiosity as the painting of coachlines and checking of panel gaps.

The only reason to point this out is to impress upon the reader to throw out preconceived notions about that this sort of book “should” contain. Bins of hose clamps and trays of yarn are shown with the same sense of curiosity as the painting of coachlines and checking of panel gaps.

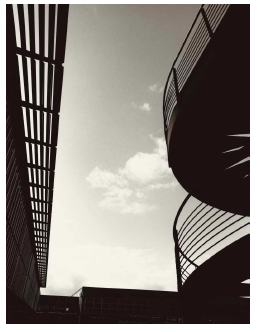

Even the undulating railings on the glass-walled, semi-sunken plant building’s roof draw the photographer’s attention (whereas the award-winning 35,000 sq m green roof planted with sedum did not). Incidentally, excitable readers (read: Rolls-Royce purists who still have not made peace with the fact that this iconic British make is now owned by BMW) will want to reach for strong drink upon seeing, for instance, an engine pulley emblazoned with the word “Germany.”

A second clue that this is less a book about something but an objet in and of itself is the name of the publisher. Gerhard Steidl in Germany makes bibliophile books—some of which costing thousands—on such a high level of craftsmanship that the Daelim Museum in Korea last year mounted an exhibit of 40 years of Steidl’s holistic approach to bookmaking and his work for and with world-class artists.  None other than Karl Lagerfeld did the poster for the “How To Make A Book With Steidl” show! For Steidl, his books are his artwork, meaning the physical properties of his books—printing technique, paper, linen, the preparation and manipulation of the imagery (in this book the photos are shot on film, not digital)—are as much an expression of art as the works of art they depict. Oh, this one is a majestic 11½ x 14¾ inches so you better have a plan how best to display it.

None other than Karl Lagerfeld did the poster for the “How To Make A Book With Steidl” show! For Steidl, his books are his artwork, meaning the physical properties of his books—printing technique, paper, linen, the preparation and manipulation of the imagery (in this book the photos are shot on film, not digital)—are as much an expression of art as the works of art they depict. Oh, this one is a majestic 11½ x 14¾ inches so you better have a plan how best to display it.

So, approach the book on that level and not as a primer on how to bolt a car together or why Step F follows Step E on the shop floor and you won’t be confused by this highly subjective way of capturing on paper the work of art that is a Rolls-Royce.

That said, would it really have weakened the book’s intended impact/effect to show thumbnails of the photos at the end of the book along with even the briefest of descriptions what they depict? Even folks who have a Phantom or Ghost will not recognize what some of these images show!

That said, would it really have weakened the book’s intended impact/effect to show thumbnails of the photos at the end of the book along with even the briefest of descriptions what they depict? Even folks who have a Phantom or Ghost will not recognize what some of these images show!

Random noise: considering that Rolls-Royce kept a close eye on this book and knowing how zealously their lawyers hunt down any use of the trademarked Rolls-Royce name by anyone outside the company or applied in any context other than the making of Rolls-Royce products, it is interesting to note that in this case a reference to the publishing house as “the Rolls-Royce of publishing” was allowed to stand.

Copyright 2014, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter