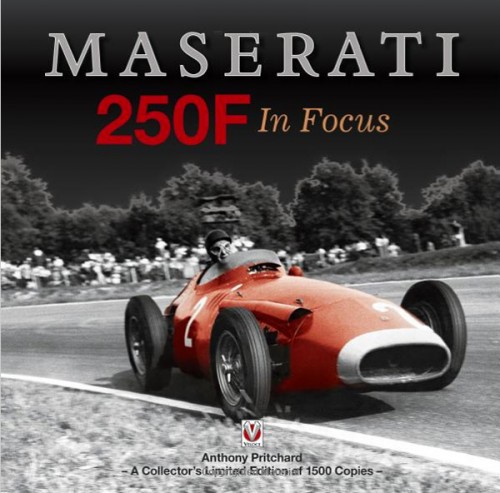

Maserati 250F In Focus

“The 250F was designed as a car that could be sold to private owners and raced by them with factory support, without being extortionately expensive by Grand Prix standards. In fact, the main intention in developing the 250F was to build these cars against customer orders.”

Conservatively, the survival rate of this lovely little racer is 200%. Yes, something is wrong with that sentence, which is one reason why books about this car keep getting written. Pritchard himself tackled the subject in 1985 and also wrote three other books about Maserati racing cars.

The introductory quote above may not sound like a big deal but consider that, at the time, only one other manufacturer did that, Connaught, and later Cooper. And customers did do well with these 250Fs, so well that they continued racing them for several years past the time the Maserati works team withdrew from racing in 1957. Even when the whole 2500 cc class for which this model had been developed was shut down in 1960, privately campaigned cars soldiered on for another couple of years—both genuine factory-built race cars but also chassis numbered as “continuation cars” or what we would today call “facsimiles”—and therein lies another reason for the peculiar complications that beset this car’s history.

The 250F is supremely pretty but that is no reason why over the decades some 80 books and countless magazine stories have dealt with it in some fashion. Nor was it blindingly competitive. So as to not repeat ourselves unnecessarily the reader is referred to our review of the one 250F book that every serious reader should have, David McKinney’s (2003, the car’s 50th anniversary). That review also assessed the pros and cons of the handful of important 250F books, pegging Pritchard’s 1985 offering as mainly of interest to completists because it added nothing fundamentally new to the record. This new book does add something new, in particular regarding the vexing problem of chassis numbers, which is the key reason why so many fakes exist. But Pritchard, an attorney by training and an unassailably thorough researcher with some 50 motoring books to his credit, is the first to say that while he cannot, does not, and does not claim to close the matter here, the account as recorded here is as accurate as is humanly possibly today. Everyone who counts in the Maserati community, the fraternity of race historians and racing folk in general have weighed in, not least Cameron Millar whom 250F enthusiasts will know as the well-intentioned but probably naive builder of the facsimile cars. Do note, however, that the sorting-out of the chassis numbers is primarily concerned with only in-period racing/ownership and only very occasionally looks at the following 45 years of history.

Also, while the book is a fully cohesive soup to nuts history of the 250F, it is not positioned as the book to supplant all previous books but as a companion effort that focuses on advancing those points that require advancing. For instance, hard-core technical detail takes a definite backseat to cleaning up the competition history (including racing numbers, laps run and other such minutia).

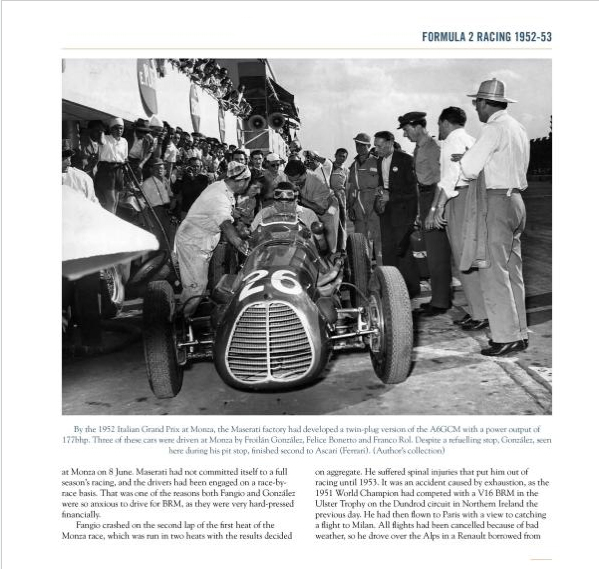

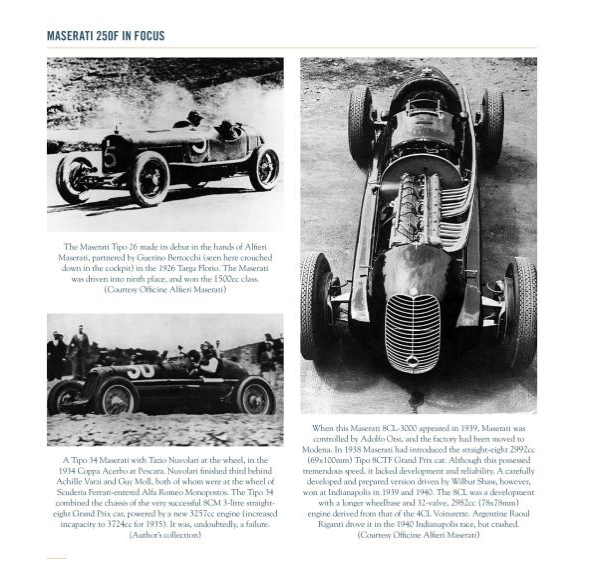

Pritchard doesn’t so much have a “writing style” as a method or approach to encircling his subject. First-hand accounts by drivers, team personnel, and mechanics always feature prominently. Against the background of the state of F2 racing in 1952/53, and in the context of Maserati’s commercial and competitive ambitions, the design and development of the 250F are dispensed with in less than 20 pages. This is followed by individual chapters covering each year between 1954 and 1958, each some 30 pages long and summarizing every [major] race. Aside from the introductory remarks there is not much overarching narrative here, the bulk of the text consisting of race commentary, drivers, cars, and stats.

Appended are two reprints of articles in The Autocar from 1955 and ’56, chassis histories, specs (mostly from the 1954 model), and a few words about the Panini Museum that houses a/the greatest collection of Maseratis.

Those readers who might say that the book seems in a few spots repetitive or not fully tweaked should recall that the author died (October 20, 2013) following a fatal traffic accident, a few months after turning in his manuscript but before work on it had run through all the pre-publication steps. A very peripheral example of avoidable vagueness is the first sentence on the dustjacket flap that singles out the “superb photos by Tom March, one of the leading motor racing photographers of the 1950s” without saying that Pritchard owned the March collection. Moreover, if such praise were to make you keen on wanting to see March photos, you’d not find a single one under his name in the book—they are credited to FotoVantage.

Being released by the publisher as a “Collector’s Limited Edition” means the book is limited to 1500 copies, which also means a somewhat higher price. The publisher, incidentally, refers to having another two books of Pritchard’s in the pipeline, to be finalized and released posthumously. Those would be Grand Prix Ferrari and Grand Prix Ford but the latter has since been published under Graham Robson’s name.

So, if the McKinney book is lonely in your bookcase, this one is a worthy partner.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter