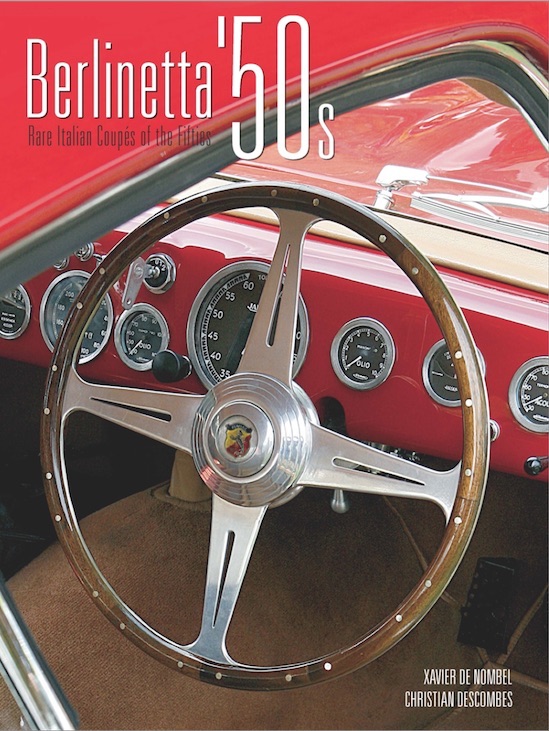

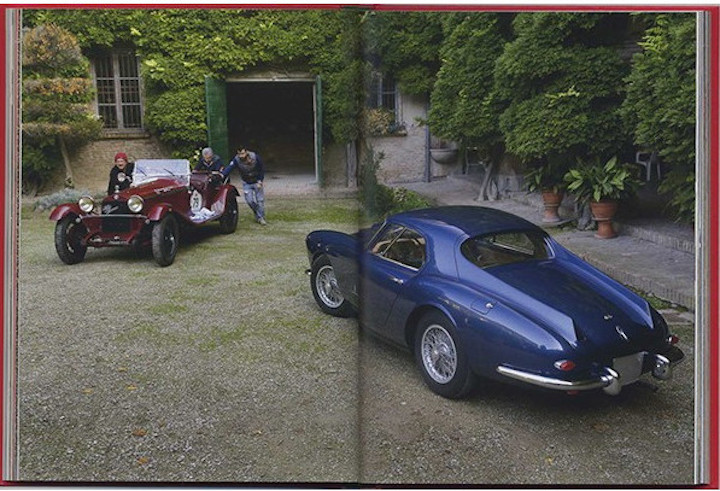

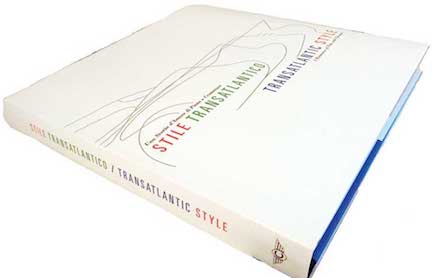

Berlinetta ‘50s: Rare Italian Coupés of the Fifties

by Christian Descombes, photos by Xavier de Nombel

by Christian Descombes, photos by Xavier de Nombel

“Cars, and in particular the design of their bodywork, had no place, in principle, among the priorities of the moment. As early as 1946, however, thanks to that very Italian ability to put the superfluous ahead of the essential when it can motivate people to get back on their feet, Italy abounded with automotive projects, with new makes of sports cars, innovative body styles and a return to motorsport.”

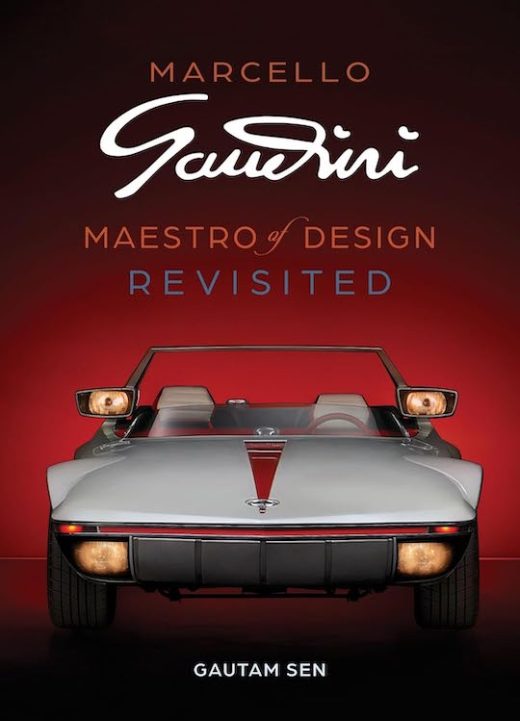

Note the bolded part in the above quote. Much ink has been spilled on the subject of why Italian design is so distinctive. Unlike the above, many of these ruminations are utter drivel, contrived, driven by that self-inflicted need to come up with a reason even if it is a half-baked one. Maybe it is that this book’s author/photographer team is French that saved it from becoming just another pointless apologia. Certainly the thorough introductory essay by Italian car designer Lorenzo Ramaciotti, which yielded that quote, steers clear of platitude. He has a comprehensive grasp of coachbuidling history and industrial practices in Italy, having joined Pininfarina right out of school (1972) and rising to various managerial positions over the next three decades before moving on to Group Chief of Design at Fiat and now Head of Design at Fiat Chrysler.

Since berlinetta means “little saloon” in Italian it should be understood that all the cars discussed here are fixed head coupes, mostly two-seaters and with an especial sporting flavor. (Even Chevrolet appropriated the term in the 1980s, hoping its halo effect would make the Camaro Berlinetta coupe appear more luxe than it was.)

Thirty-seven cars are covered—obviously there are more, many more, and also a much greater variety of coachbuilders/designers (easily a good 30% of the cars here are by just Michelotti) which leads the reader to conclude that the cars featured here must be the ones the authors like best (or had the most unfettered access to because all the cars are said to have been specifically photographed for this book; they are augmented by a few period photos from the makers’ archives).

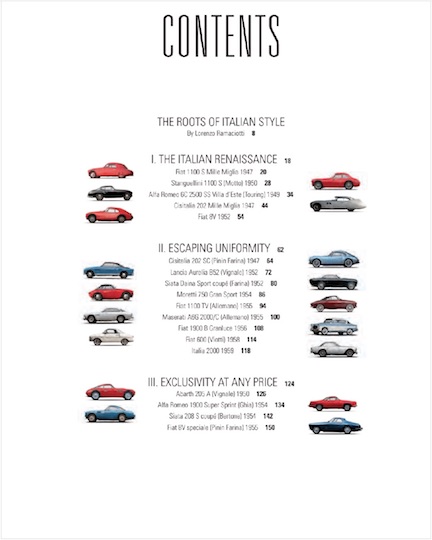

The book begins with the oldest (1947) and ends with the youngest (1960) but the other 35 cars discussed in between only loosely follow a chronological order. Instead, each of the five chapters explores a theme, and each particular theme is structured more or less chronologically. In the absence of an Index the very finely detailed Table of Contents is an excellent guide to coachbuilders and models. Near the back of the book is a list of all the cars in year order and with a page reference.

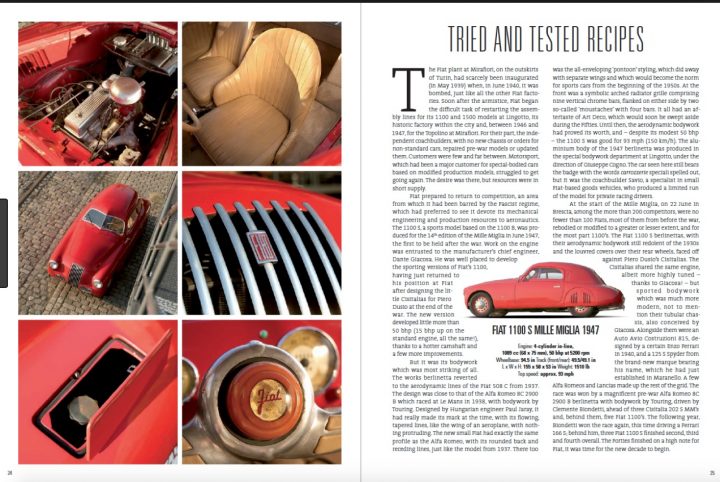

Each chapter is introduced by half a page of text, and each car by one page, including a short data bloc of basic specs. In other words, there isn’t a lot of overarching narrative, nor, for that matter, granular detail about the specific cars shown (no serial or chassis numbers, for instance). On the writing side, Descombes with a quarter century of editorial work for the French magazine Automobiles Classiques under his belt is certainly no stranger to the subject so the fact that the book, in the main, relies on photos to carry the story is surely a conscious choice. Mini bios of 38 coachbuilders and designers and a list of key dates between 1947 and ’61 round out the book.

Having been published originally in French by Camino Verde (ISBN 979-1090267275) the book has been very nicely translated into English, is appealingly designed, and very well printed including such high-end features as four tipped-in coachwork illustrations on glassine paper and a sturdy slipcase.

Having been published originally in French by Camino Verde (ISBN 979-1090267275) the book has been very nicely translated into English, is appealingly designed, and very well printed including such high-end features as four tipped-in coachwork illustrations on glassine paper and a sturdy slipcase.

Copyright 2017, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter