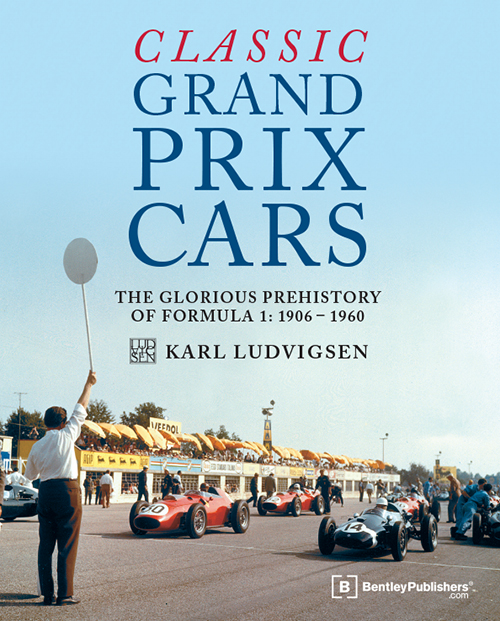

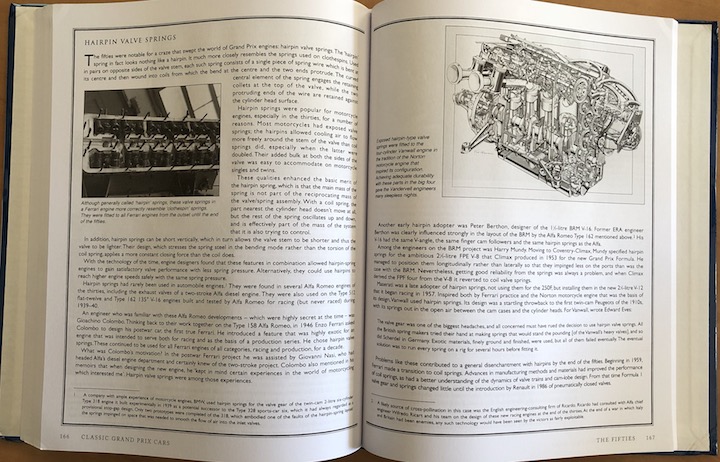

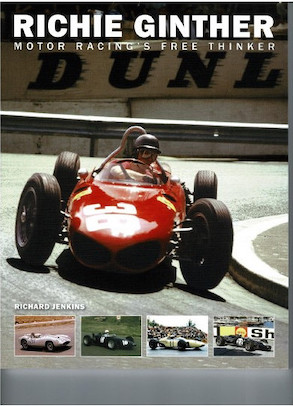

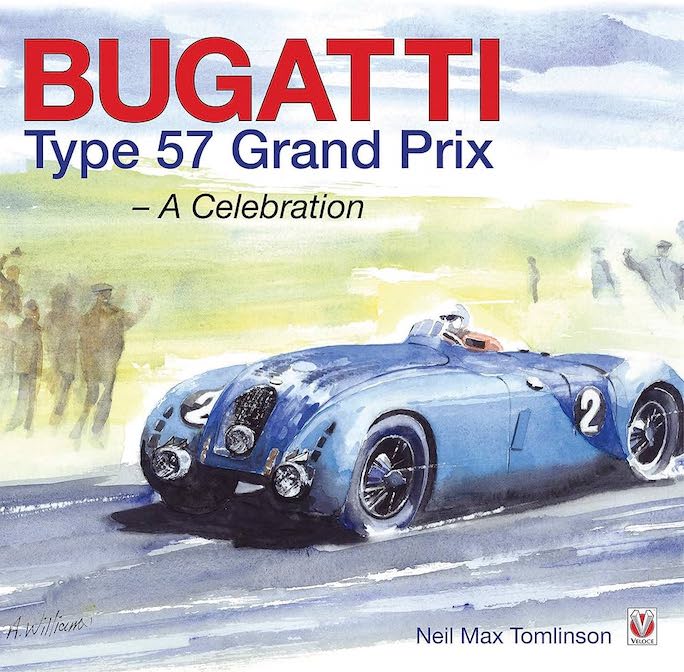

Classic Grand Prix Cars

The Glorious Prehistory of Formula 1: 1906–1960

“The reader expecting a blow-by-blow account of the races of these years will be disappointed. I hope I’ve given a clear sense of the top dogs and lesser beasts of each period but the rote recital of racing results has not been my aim. Rather, the text and illustrations endeavor to provide a fresh view of the way Grand Prix cars of each decade evolved, sometimes illuminated—perhaps unfairly—by what we have since learned about the cars and the men and companies that made them.”

Since this book, first published in 2000 (Sutton) and then again in 2006 (Haynes), is very much and very rightly a cornerstone in a serious motoring library we ought to address those readers who have an earlier version first.

Usually, when a new edition comes out, people who have an earlier one are confronted with the near impossible task of sussing out what, if anything, is new and different. This doesn’t apply here as this is, except for the Introduction, a straight reprint—but that has its own problems: the book is frozen in time, warts and all, while the body of knowledge has advanced. Ludvigsen is a singularly thorough scholar and especially, for instance, his own work in the field of Porsche shows him circling back to his own earlier work and incorporate, in subsequent books, new facts into the record and thereby amend his earlier interpretations. The one example we will use here to illustrate this pickle is, on the one hand, really rather peripheral to the topic of this book, but, on the other, is a perfect, and painfully high-level (meaning easy to ferret out, evaluate, verify) issue. Page 9 repeats the old chestnut of W.O. Bentley describing the engine of the 1914 Mercedes GP car being shipped to Rolls-Royce for testing. This did happen, but not the way W.O. remembered it or recorded it (these being two separate issues, but that’s its own story). Him writing “ . . . all Rolls-Royce aero engines built during WW I were based quite closely on this engine” has been debunked years ago after the discovery of RR’s internal R&D records established a different timeline disproving that their engine work could have been based on the Mercedes motor. RR folk take violent exception to this statement and even a mere new footnote, for which there is space on the page, would have helped. It muddies the waters for a new generation of reader to let this quote stand uncontested.

But, back to the big picture: the book remains a standout, not least in how it makes its potentially dry subject matter exciting. This is because its author is excited, moved by the poetry he sees in engineering and ideas and bits of metal. Already when the book first came out, almost two decades ago, it was that quality that elevated it and that tied it to the work of the great exponents of this type of writing. In fact, Ludvigsen retained in the variously rewritten forewords to the three versions a tip of the hat to the sainted Laurence Pomeroy’s way of carving the turkey. The new intro is now almost twice as long because it goes into some detail about chapters 6 and 7 that chart the transition to rear-mounted engines, which in turn relates to the book’s new subtitle: The Glorious Prehistory of Formula 1: 1906–1960 (formerly The Front-Engined Formula 1 Era 1906–1960).

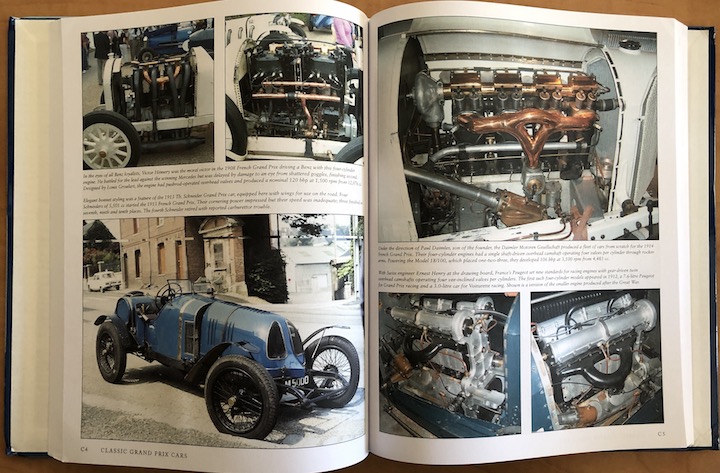

The book has an ever so slightly altered physical format, a bit shorter and wider. And while the paper now may be acid free it is also matte which does nothing for the sharpness of the photos. Compared to the original, the color section has moved to different pages and the photos are reshuffled and sometimes at different sizes, for no apparent gain. Anyone who has the older editions (the 2006 book had more color than the 2000 one) is almost certainly better off cherishing those, and cherish the fact that they paid less than the new one costs.

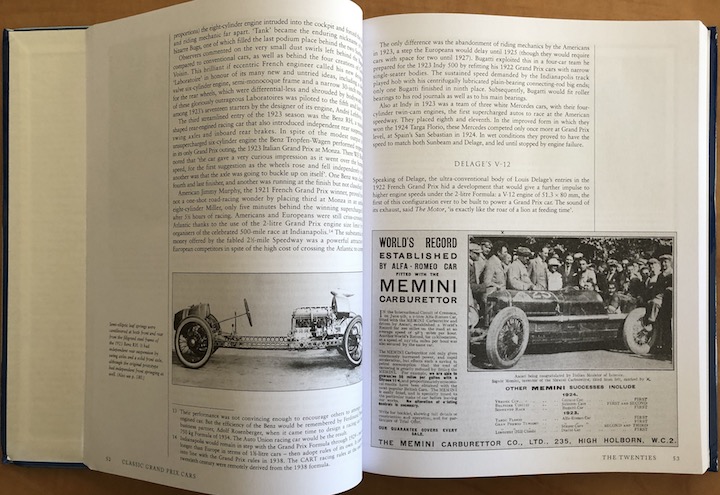

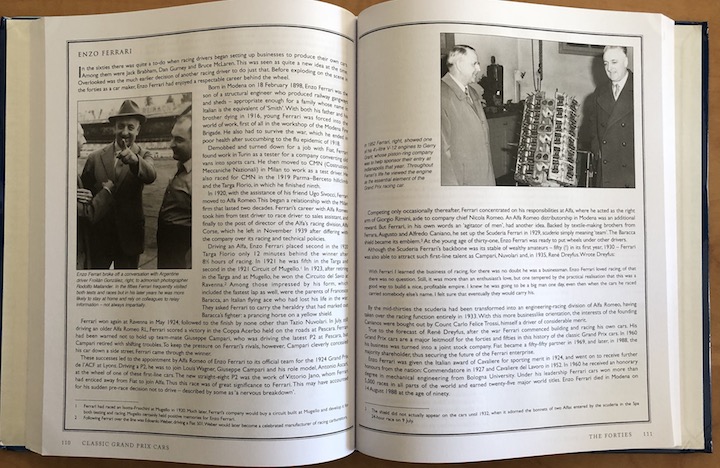

Chapters 1 and 2 lay the groundwork, explaining the purpose of motor racing, the methodology and participants, technologies tried and discarded. This is a fine primer for anyone who quickly wants to get up to speed. (Yes, yes, there’s a pun in there.) The remaining chapters advance by decade and the key item to know here is that this is not a book about race action or personalities or tracks but a book about the why and how of motive force. As the material was originally developed for Automobile Quarterly magazine it is heavy on narrative and illustration and easy on hardcore tech, graphs, and math etc.

For those who are only discovering Karl Ludvigsen now that he has half a century and more of top-notch automotive writing under his belt, this book is a marker for how high an orbit he travels in and what a pillar of the automotive community he is and has been. His focus has shifted away from automobiles, sigh, for some years now, but he ain’t done writing yet. (Readers who have his epic Corvette book Vol. 1, fear not, Vol. 2 is underway.)

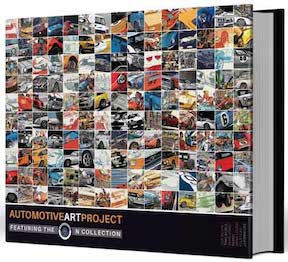

If you don’t already have an earlier version of Classic Grand Prix Cars, be glad that the publisher who now holds the rights to the book has brought it back to market, along with two related others, Classic Racing Engines and The V12 Engine.

Copyright 2018, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter