Searching for Charlie, In Pursuit of the Real Charles Upham VC & Bar

Your reviewer’s memories of the Anzac Day Parades every April 25th date from the early 1950s. On that late autumn day, a small contingent of survivors from the South African War (1899–1902) marched as best they could ahead of still vigorous veterans of the First World War (1914–18). New Zealand servicemen fared particularly badly in that war; out of a population of just over 1 million, 98,950 served overseas, 80% volunteers, and 18,058 died.

Returned servicemen of the Second World War marched particularly proudly, and a man we knew as “Captain Upham” was always present.

The April date commemorated the disastrous 1915 landings at Gallipoli Peninsula, when the Turkish government of the Ottoman Empire used the excuse of perceived collaboration with Russian troops to exterminate the Christians, Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks, to describe which the word Genocide was coined. It still echoes, 105 years later.

Although prominent members of the Labour Government had been Conscientious Objectors 25 years earlier, the official policy was “Where Britain goes, we go,” and New Zealand was officially at war with Germany, 12,000 miles away, within hours of Britain’s declaration of War on 3 September 1939.

Among the first to volunteer at Burnham Army Camp was Charles Hazlitt Upham (1908–94), a relative of the 18th Century essayist William Hazlitt. After a spartan education at boarding schools from the age of eight, he studied at Canterbury Agricultural College, Lincoln, and after graduating in 1930 he had spent the intervening nine years working on the land, as fencer, scrub-cutter, musterer of sheep, rabbit shooter, wild pig hunter, farm manager, and valuer. He was quickly noted as a potential leader, but, anxious to defeat the enemy, he declined Officer training, and was on his way to further training in Egypt by that December with the rank of sergeant, and in a uniform left over from the First World War.

Most New Zealanders of a certain age had access to a book on their parents’ bookshelf, Mark of the Lion by Ken Sandford (Hutchinson 1962). Sandford (1916–2005), a lawyer in a provincial city, had written some detective novels, and was diplomatic and skilful enough to circumvent the caution of the intensely private Charles Upham. His biography of the man was well received, during an era when memories were still available first-hand.

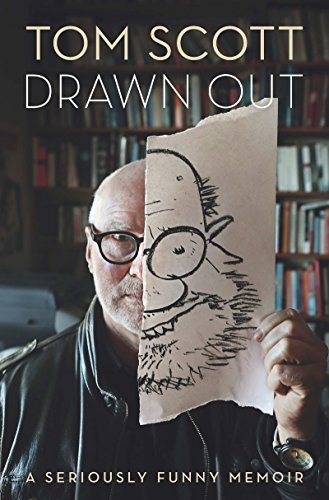

Tom Scott, whose memoir Drawn Out (Allen & Unwin 2017) is reviewed on this site, was one of those who absorbed Sandford’s book at an impressionable age, and after bringing various projects about another local hero, mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary, to fruition, he started work on Searching for Charlie. The travel involved, to Egypt, Italy, Germany and Australia, was completed before the recent pandemic, and the logistics of book publication in New Zealand, with printing in China have been solved.

Tom Scott, whose memoir Drawn Out (Allen & Unwin 2017) is reviewed on this site, was one of those who absorbed Sandford’s book at an impressionable age, and after bringing various projects about another local hero, mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary, to fruition, he started work on Searching for Charlie. The travel involved, to Egypt, Italy, Germany and Australia, was completed before the recent pandemic, and the logistics of book publication in New Zealand, with printing in China have been solved.

By 1940, the war was not going well for Britain and her British Commonwealth allies, with the disastrous campaign in Norway and the evacuation from Dunkirk in France. After further training in Egypt, the New Zealand Division was deployed to Greece, to join the British “W Force” and ill-equipped soldiers from Greece (then at war with Italy but not Germany) and Yugoslavia to face German panzers which had blasted their way through Albania and Yugoslavia to advance south into Greece. By this time, Upham had been commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant, in charge of a platoon of twelve soldiers, but with no air defense against the estimated thousand aircraft wreaking havoc on supply convoys, armies and refugees alike, the evacuation organized by pragmatic planners took what was left of W Force from various ports to the island of Crete in April 1941, leaving behind most of their equipment.

By this time the German code system, “Ultra,” had been broken, but the knowledge that Nazi forces ready to invade Crete included 35,000 men (including 12,000 parachutists), 150 bombers, and 100 fighters could not be acted upon. Not that that would have helped a badly outnumbered W Force; after three weeks of bombing and strafing, the airborne invasion happened on 21 May 1941.

Scott provides great detail, gleaned first- or second-hand, of the ferocious hand-to-hand fighting which initially went so badly for Germany that Hitler ordered Goebbels to conceal the news, but eventually what was left of W Force was evacuated to Alexandria, by the end of the month. For sustained acts of bravery in Crete, Charles Hazlitt Upham was recommended for Britain’s highest honor, the Victoria Cross “for valour,” and in the Western Desert he continued an insane-seeming campaign of grenade attacks from the stash in his haversack. He suffered many wounds, one of which permanently disabled his left arm, until eventually, unable to walk, and cut off by General Rommel’s tanks, he was taken prisoner on 15 July 1942.

Upham then endured almost three years of captivity, spiced by enough attempts to escape to earn him eventual incarceration in Oflag IV-C, the notorious Colditz Castle. A second Victoria Cross had been awarded, as well as a Mention in Dispatches for his attempts to escape, and when his medals were invested by King George VI on 11 May 1945, the reply to the King’s question of his activities since repatriation was, “Mostly eating, Sir.”

Until frailty forced retreat to rest in Christchurch, Charles Upham farmed sheep near the coast of north Canterbury, having married his prewar fiancée before returning to New Zealand, and had twins and a later daughter, one of whom impressed the author of a “Talk of the Town” item in The New Yorker. Upham’s life cannot have ever been easy, and Scott is able to convey the avoidance of any treatment perceived to be “special” as he coped with whatever mental scars he bore. He can’t have been an easy person to know, and Scott has been able to navigate the divergent impressions provided by his sources, and to give us at least an inkling of what went on behind Captain Upham’s penetrating blue-eyed gaze.

The humorist Robert Benchley (1889–1945) wrote of his slightly awkward friendship with Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), looking back on visits “after the furniture has been repaired.” Noticing Benchley’s collection of Hemingway First Editions, the author went through them, filling in the publisher’s blanks with the naughty words, thus rendering the books unsalable in that pre-Lady Chatterley era. This brings us to the contrast between the rather reticent Sandford and the exuberant Scott. There must be many readers who prefer blanks to cusses, and to take as a given “the rude, licentious soldiery.” Euphemism is not evident in Searching for Charlie, and speech is often reported, either remembered or constructed. The appalling conditions faced by opposing armies are reported in gruesome detail.

Scott writes well, in proper sentences, but it would be a braver man than your reviewer to presume to address the subject of his book as “Charlie,” a more appropriate first name seeming to be “Captain.”

Copyright 2020, Tom King (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter