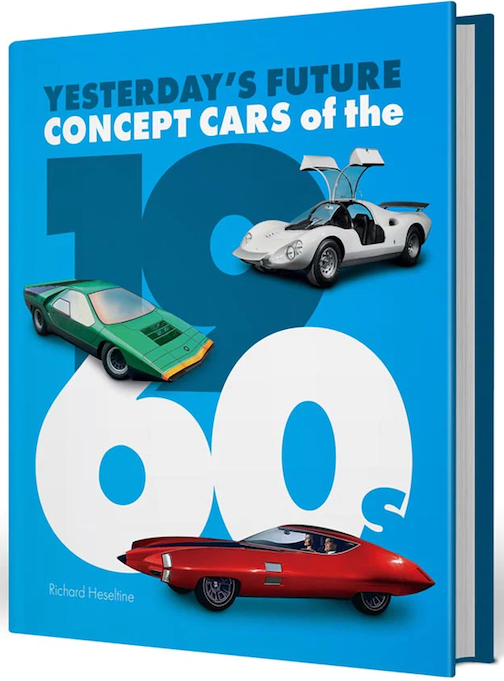

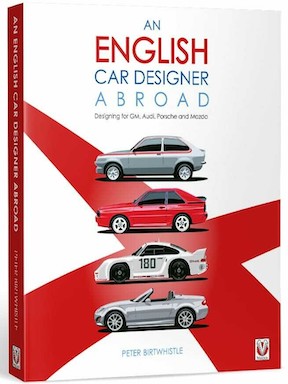

Concept Cars of the 1960s: Yesterday’s Future

by Richard Heseltine

by Richard Heseltine

“Caution equals cowardice. Concept cars, dream cars, teasers—call them what you will—are meant to break moulds and push envelopes; to forecast or establish trends. Designers by their very nature have a propulsive desire to seek out the horizon, to create the kinds of artistic tour de force that makes the whole world sit up and take notice. Concept cars afford them the opportunity to let rip; to use their imaginations and envisage the sort of vehicle that we will be driving in years—perhaps decades—to come.

At least that is the theory.”

With apologies to the author who will think this hopelessly puerile . . . but how can one resist, and besides, he writes himself that “the name is guaranteed to reduce English speakers to a fit of giggles”: Ferrari once put a FART into the world, a FART Break to be precise. Never heard of it? Well, it wasn’t that Ferrari for one thing.

And how’s this: what is a Tse-Tse? Who made the Punch Buggy? What was voted “safest car in the world” in 1963? And do you really believe Oldsmobile made a snowplow? Out of a Toronado that had its front and rear ends chopped off?? You betcha. GM used it for years, in fact they built a 4-door version as well. If you already own books on concept cars, they probably don’t include any of these. But don’t worry that this book is strictly about fringe exotica—there are plenty of cars that even the casual car person would/should recognize such as the Ferrari Tre Posti, the Chrysler Turbine Car, or Alfa Romeo Carabo.

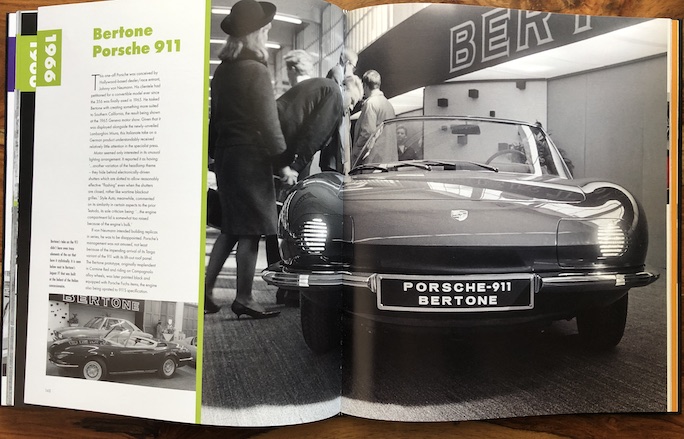

Obviously a model name any car person will recognize. This one-off was unveiled alongside the Miura, which stole the show, but Porsche was miffed already anyway because they had not authorized this build.

Even without knowing any of this before you pick up the book, it spells FUN just sitting on your desk, its splashy cover and larger than average size (11 x 12.5″) drawing the eye away from the sea of serious car books. Not that there is anything not serious about this book. First of all it’s by Porter Press and those folks don’t waste ink on fluff. Secondly it’s by longtime author Richard Heseltine. And thirdly it’s meant to be the first in a new series so it has to make a good first impression.

These are just three of the ideas for 1969, and they are all over the place. A quaint chauffeur-driven Lincoln reminiscent of the Days of Yore and a Buick to be steered by punch card on the electronic highway. By comparison the Tom Tjaarda-designed Isuzu seems like a perfectly realizable idea but it too was not build—until it would become the foundation for the Pantera later.

Heseltine begins with a quick romp through time. Why did carriages always look like . . . carriages? What combination of factors had to line up just so to go beyond “function” to “form”? And even when there was such a thing as car styling, why was it initially dismissed as a frivolity? Whole books have been devoted to any of these topics so the brief treatment here is merely to set the scene for the idea of the concept car, first and foremost in the US. Obviously, GM’s Harley Earl gets top billing here, Heseltine adding enough caveats to the statement “arguably the first professional car stylist in the accepted sense” to deflect the argument that Earl really was not the first practitioner. A minor snafu here is that Heseltine, who is a Brit and therefore would have an automatic pass if he defaulted to British spellings, misspells Earl’s department as “Art and Color Section” when Earl specifically, intentionally, and to the exasperation of many insisted on spelling it “Colour.”

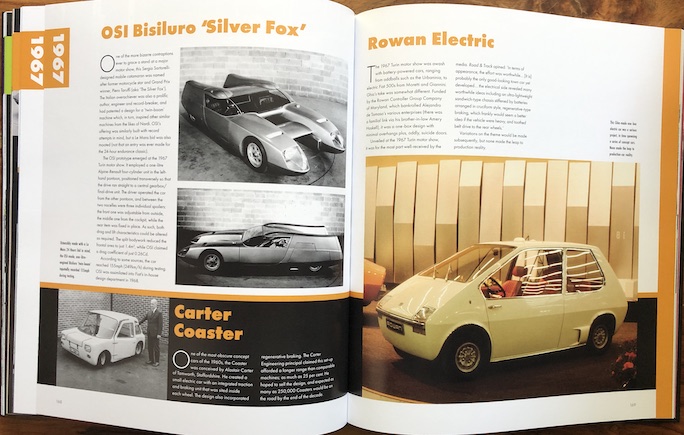

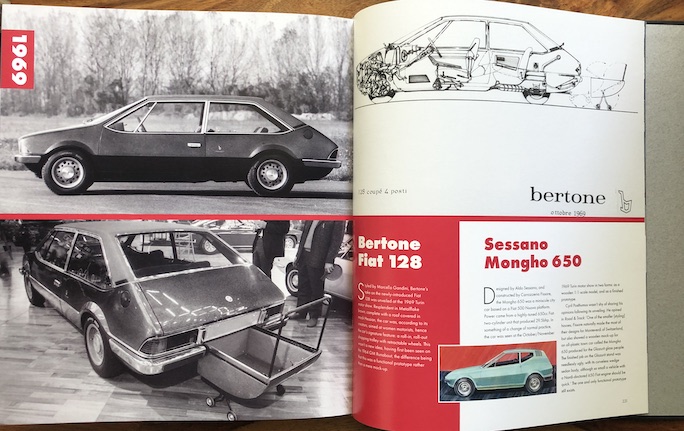

This is page 168. Pretty much every page of the book echoes a sentence from the very beginning of the book: “It’s so easy to tie yourself into knots trying to define what constitutes a concept car.”

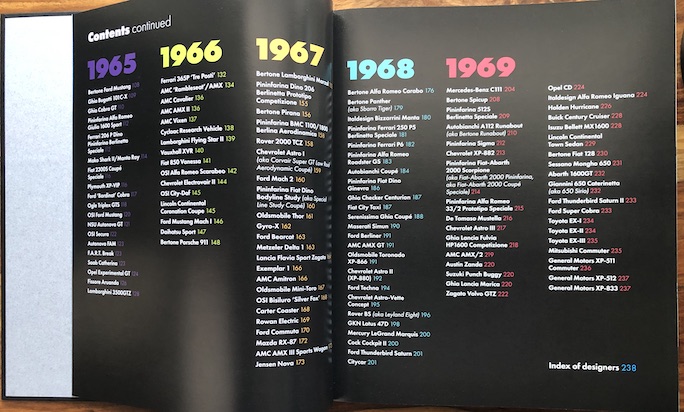

The book is divided into years, 1960–1969, each year beginning with brief synopsis of automotive trends as well as a secular timeline just to jog readers’ memories of where they themselves might have been (at). This is followed by a wide-ranging but high-level discussion (meaning lots of context but limited depth; this is not a criticism or shortcoming but merely a description of the MO) of about 200 individual cars, one to a page, often accompanied by excerpts from media reports. Surely there is an organizing principle behind the order in which cars are introduced, but we are unable to find it. Doesn’t matter; just consult the Table of Contents (there are two Indices, one for Designers and one for Design Companies but none for Cars).

Answers for “right now” are obviously always on a designer’s mind. Shopping carts are a good example. Clearly there is a need (or is there?) but neither the 1964 GM Runabout nor this 1969 Fiat met it.

Heseltine’s premise is that he 1960s were prime time for the concept car, and the book gives ample evidence of it, not least by the fact that the proposals range from the almost mundane but practical (built-in shopping carts, above) to the utterly unbuildable and fundamentally unenjoyable (absurdly large greenhouses impossible to effectively cool/defog; and just try getting out of a car with a forward-sliding or upward-tilting “cockpit canopy” in the rain). That some of these ideas never even made it off the drawing board does not diminish their value as thought exercises. Unless you are a car designer this book will have much new to offer, and even if you are it’s a colorful retrospective and also inspiration.

As to the publisher’s thinking to turn this into a series: yes, please.

Copyright 2022, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter