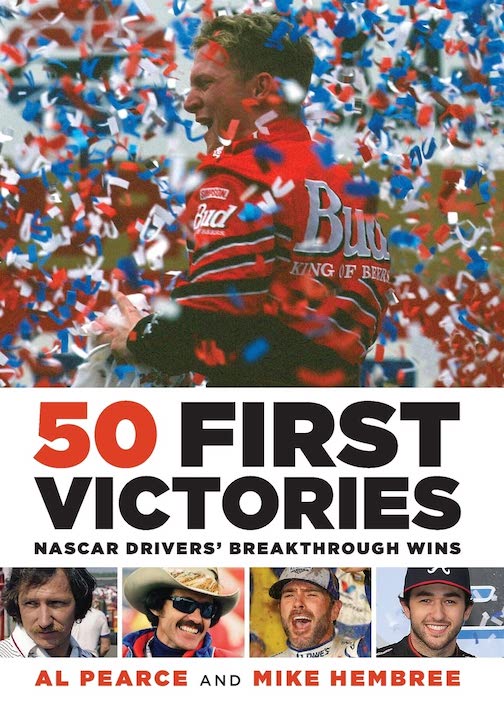

50 First Victories, NASCAR Drivers’ Breakthrough Wins

by Al Pearce and Mike Hembree

by Al Pearce and Mike Hembree

“It is ironic that Bobby Allison made his name by winning NASCAR Cup Series races on long, fast, high-banked superspeedways in the South. Ironic, because the first of his eighty-four career victories came on a tiny, rough-and-tumble, backwoods bullring in central Maine—about as far from his south Florida and Alabama roots as possible.”

That excerpt is a good representation of the book’s approach: a driver may become known for all sorts of activities or all sorts of reasons but the circumstances that surround his first win, especially if it came in an entirely different venue/series, may become forgotten. This book looks at 50 examples from mostly the NASCAR world, and if you wonder how the authors settled on that nice round number when there are obviously more than 50, the common denominator is that the wins were especially unusual/noteworthy.

This criteria is unavoidably subjective and the response to that is the fact that the two authors’ combined ninety years of motorsports reportage and analyses lend weight and context to their pronouncements. That won’t stop anyone from complaining that things did not really go down the way they are presented here—but, in a way, that is really the main benefit of this book: to refresh the memory and/or prompt a rethink.

The earliest win presented in this book dates to 1949, Jim Roper who died in 2000, which indicates that secondary sources such as period newspaper or race reports had to be mined when the protagonists are no longer alive. The thing is, even when they are there is not always agreement or even reliable and comprehensive recall to be had about points of view literal and figurative. Wins don’t just drop into your lap with a bow on, they are fought for and that means elbows-out driving, provocation, self-interest, risk, even the occasional fist fight. Or team orders . . .! This points to a, probably unavoidable, limitation of the book: it is descriptive (who, what, where) more than analytical (why). Ergo plenty of questions will remain after reading this book.

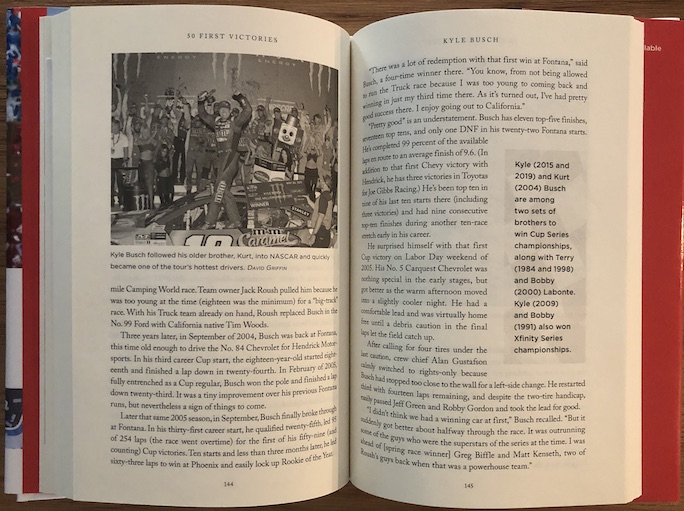

Almost all profiles include one or more sidebars that add useful snippets to the main narrative.

Absent any guidance from authors or publisher both the expert reader and the novice will look at the Table of Contents in wonderment because no apparent order is evident (year; alpha; ranking, implied or otherwise). To lift a sentence from the really fine Foreword by Kyle Petty (whose own 1986 win is in the book): “Take it chapter by chapter at your own leisure or devour the whole book over a weekend.” Now consider that for instance the first four chapters take you from 1979 to 1960 to 1994 to 1949. This whiplash approach will prevent the novice from forming a cohesive impression of changes within the sport while the expert will inevitably get bogged down in ruminations about why Jeff Gordon is “high up” in ch 3 but Michael Waltrip “way down” in ch 46. This is not the authors’ first rodeo so they surely have a reason for their process—why not share it with the reader? The Index, which is really well layered, is probably the safest way to start.

Pearce is Autoweek’s senior motorsports writer and Hembree a contributor. The review of their book in that magazine describes it as “loaded with pictures.” Unless the reviewer was looking at a different version of the book, or not looking at all (he got a different page count) that is a wild overstatement. Photo coverage is passable (also only b/w) and in the old material mostly absent.

How the authors divided the labor is not disclosed so for those who don’t already know, it should be said that each has written more than a dozen books, covered hundreds and thousands of races, and Hembree (who also reports on other sports) has a bucket of journalism awards.

Copyright 2022, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter