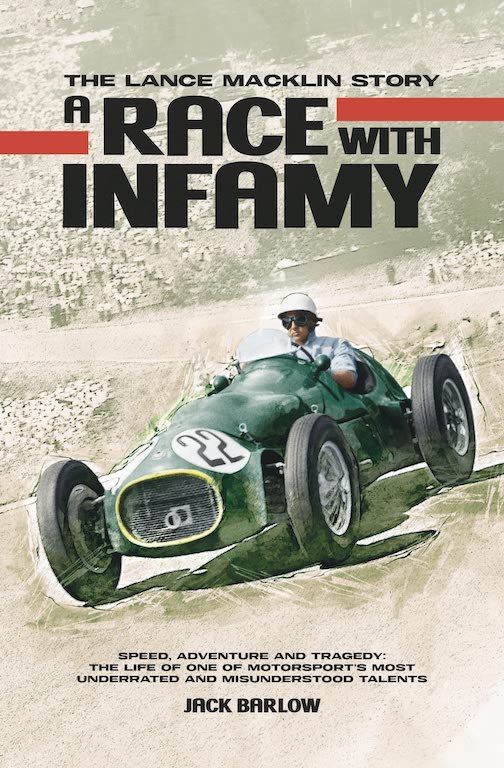

A Race With Infamy, The Lance Macklin Story

by Jack Barlow

by Jack Barlow

“It was as if all the nervousness he’d felt after Le Mans, all the fear that came over him every time he sat in a racing car, had been realised in the most horrible way possible.”

—the aftermath of Dundrod, 1955

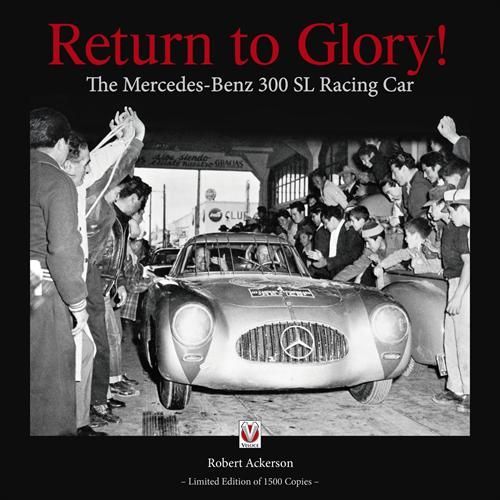

Lance Macklin (b. 1919) was one of many talented British racing drivers who enjoyed success in 1950s’ sportscar and single-seater racing. What sets him apart is his central role in, but arguably not culpability for, the 1955 Le Mans crash that resulted in the death of 83 spectators as Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes 300 SLR scythed through a packed grandstand. This book pivots around that one defining incident, when Macklin’s Healey, having swerved to avoid a collision with Mike Hawthorn’s rapidly slowing D-Type Jaguar, was collected by the charging Mercedes. The repercussions of the accident changed motorsport forever, including the ban on racing that exists to this day in Switzerland.

Although Macklin died in 2002, his racing career went largely unmarked until Jack Barlow’s book. It is a small book, 8” x 5”, 216 pages, but being the only one to date it will loom large in the literature, entirely irrespective of whatever merits it may have.

The story of Macklin’s long and colorful life is told in a rather breathless style, with few verbs escaping an adverb, even fewer nouns an adjective, and with a profusion of quotations supplemented by the protagonist’s alleged/imagined thoughts.

The author describes Macklin as a charming, charismatic rogue, a stranger to both meaningful employment and marital fidelity. Macklin’s father Noel sounds similarly unsavory, indulging in such crass pranks as heating up coins before discarding them in the hope urchins would pick them up (was this really what passed for innocent fun in Macklin senior’s social circle?) but at least he etched his name into motoring history by founding the Invicta marque in 1925. I wondered how much of Noel’s character was inherited by his son, and whether Lance’s own efforts in motorsport and car sales echoed the difficult father/son dynamic of Sir Malcolm Campbell and his son Donald. Lance’s own son Paddy reflected “I think he was overwhelmed by his father. He felt like he’d failed him somehow. He could never come up to his standards.” But, as the book goes on to recount, Lance never tried especially hard to achieve anything other than a life unsullied by hard work, and in this ambition he was to prove remarkably successful.

After a creditable wartime career, Macklin established himself quickly as a skilled race driver, getting an early break with an Aston Martin works drive, after excelling at Spa Francorchamps in his friend’s Barnato Hassan Bentley. He went on to enjoy success not only in sportscars but also with HWM, with whom he won the Daily Express British Racing Drivers Club race at Silverstone in 1952. It was his day of days, and the author touchingly recounts how, looking at the trophy in his old age, Macklin “would think back to that overcast afternoon . . . when, for one fleeting moment, everything went right.” But as legendary race mechanic Alf Francis had already said, “I am sure that if Macklin had tried really hard he could have equalled Moss.” The results of the remainder of his career suggested he didn’t try quite hard enough, especially to get a seat in the right car. Drives in the bizarre-looking and under-performing Bristol 450 and the Healey he drove at Le Mans marked a downward trajectory, even though his performance in the 1954 Mille Miglia was remarkable. There, driving his Austin Healey 100S solo, he finished a credit-worthy 23rd overall on one of the toughest road races of all.

And then came Le Mans 1955, the darkest day motorsport has ever known. The crash became the fulcrum upon which the remainder of Macklin’s life was to turn. So much has already been written about it that it seems almost gratuitous to re-open old wounds. And wounds they were for Macklin, the driver whose reactions to Mike Hawthorn’s Jaguar swerving across his path to make the pit entry in undue suddenness caught the driver behind him, Levegh, unawares and thereby played an inadvertent but crucial role in the unfolding of the catastrophic accident. Misjudgments happen in split seconds on a race track, but the luxury of hindsight enables us to apportion blame in our society which now demands a culprit, regardless of circumstances or intent. The author rightly blames nobody but acknowledges the complementary factors—Levegh’s fractional misjudgment (and perhaps Mercedes’ error in selecting him in the first place), Macklin’s actions to avoid a collision, and Hawthorn’s last-second decision to pit. Hawthorn went on to win the race, of course, and while few will have blamed him for that alone, his celebrations of victory “. . . happily holding an open bottle of champagne . . . were treated with scorn by the French press.” Insensitive, or simply crass?

Although Macklin continued to race, “the deaths kept coming”—Mike Keen at Goodwood in August 1955, and Jim Mayer and Bill Smith at Dundrod the next month. Understandably, it was all too much; “For all intents and purposes it was over. He just couldn’t do it any more.” The remaining years of his long life (he died, at 83, in 2002) are recounted in the last third of the book. Lance Macklin never had employment in the conventional sense, drifting in and out of prestige car sales with Facel Vega and Jack Barclay before embarking on a succession of doomed business ventures, culminating in the ignominy of a failed fish and chip shop business in New Zealand. About which the author writes, “To nobody’s surprise, Lance proved to be singularly unsuited for the hard work it needed to run a profit, and quickly lost interest, handing off most of the day-to-day operations to his overworked wife.”

Macklin’s wives and girlfriends, often in parallel, had to endure a lazy and unfaithful charmer, as Shelagh Macklin had commented: “He did as little as he could, he would get up late . . . then have a nice late morning drink . . . then would wander down to the Action Automobile . . . and have a long, lengthy lunch.” In only one area of activity did Macklin truly excel, later admitting to a friend that “For a man living that sort of life in Paris, the sexual temptations are very great. Paris is very well organised from a man’s point of view.”

Macklin was undoubtedly a competent and skilled race driver but his life carried the reek of unearned privilege and entitlement. He was the sort of charming cad whom my late father would have warned his daughters was NSIT – “not safe in taxis.” He was a peripheral figure in the world of 1950s motorsport, the Rosencrantz or Guildenstern to Hawthorn’s or Moss’ Hamlet, and the essence of his life story is the rise and decline of a playboy chancer, womanizer, and sometime racer. The book is not quite a hagiography, as Macklin’s faults are chronicled at length, but the reader is left to wonder whether the subject would have merited a biography had it not been for the long shadow cast by the horrors which took place at 6:26pm, 11 June 1955.

Copyright 2022, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

A very interesting review though it seems it’s more a review of Lance Macklin and his virtues and flaws than of the book itself. Clearly he lived a life that will amuse some and dismay others and it’s to Jack Barlow’s credit he has given a full and insightful portrait that allows readers to reach their own conclusions.

And of course every reader is entitled to his or her opinion of Barlow’s writing style. I thoroughly enjoyed it. The book has great pace and the writing is colourful and intelligent without relying on lazy cliches. Many biographies are a bit like watching a documentary; this one was more like watching a well made movie!

Most motorsport biographies quite naturally focus on the subject’s racing career. By telling a full life story this book, more than any other I can think of, let me into the world of the subject. I was left with a strong impression that for all his flaws, Lance Macklin was a charming and thoughtful man and while he clearly exasperated many who knew him, they were all very fond of him. It’s sad to learn the effect Le Mans 55 had on him and his mental health but if he had been able to simply shrug off such a tragedy he would surely have been a lesser man.

“A profusion of quotations supplemented by the protagonist’s alleged/imagined thoughts.”

As the father of the author I feel obliged to point out the ‘alleged/imagined thoughts’ were all based on either Macklin’s own words, or on the recollection of people the author spoke to. Nothing was made up, as you seem to imply.

I thoroughly enjoyed this amusing book. And that’s because Lance Macklin was a fascinating man. We should be thankful someone thought to write about him. Sure, many drivers had more glittering careers but that’s not the point of this book – people who are the most interesting to read about aren’t necessarily the ones who achieved the most. Most modern drivers will never make for interesting biographies but those heroes of the early, lethal days of motor racing were a different breed. This book made me feel Lance Macklin was someone I would have enjoyed being around.