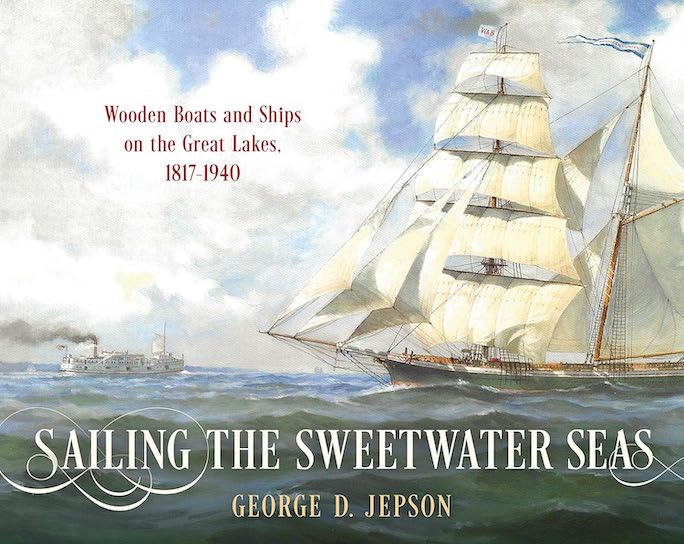

Sailing the Sweetwater Seas

Wooden Boats and Ships on the Great Lakes, 1817–1940

by George D. Jepson

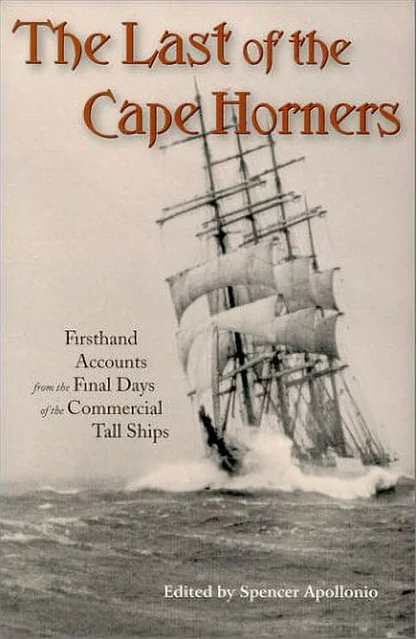

“There were also barks and barkentines working on the Great Lakes. These three-masted vessels were often loosely referred to as schooners. On barks, however, the foremast and sometimes their main masts carried square sails. Barkentine foremasts carried square sails, while the main and mizzen masts had fore-and-aft rigs. Barkentines were proportionally long and narrow, allowing them to navigate the canals.”

This excerpt is from very early in the book and the reason it throws around words only a quite specialized reader would know is because it was not written from scratch for a general audience but is adapted from a series of articles originally written for the quarterly magazine Wooden Boat, founded in 1974 with the mandate to cater “to individuals who are deeply experienced in the world of wooden boats.”

However, even if raffee or shoal-draft or mosquito fleet are not in your everyday vocabulary, this book has many interesting and relatable things to say and show, taking you to the time just after the War of 1812 when the land and its people are beginning to recover and rebuild—which means commerce is getting into gear again, which means transportation is begging to be improved. This is basically the age of the covered wagon limited in range and capacity, and railroad service is still in its infancy. And the place, well, that is surely familiar to just about any American, Gitche Gumee, the Ojibwe people’s word for Shining Big-Sea-Water immortalized in Longfellow’s famous poem. In other words, the Great Lakes.

Author Jepson grew up on its shores, in the 1940s and ‘50s, with a passion for boats because his family had worked on and with boats for generations. Growing up, Jepson knew some of that history but only later in life discovered just how far back it reached, probably to the 1870s to an ancestor who worked in the schooner trade and then moved on to steamers.

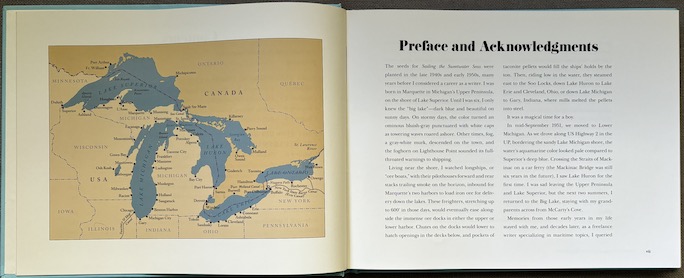

As the Great Lakes are at the center of the story, Jepson begins with the opening of the Eerie Canal in 1825 because it connected four of the “Five Sisters”—Eerie, Huron, Michigan, Superior—to the world, i.e. the Atlantic. (Lake Ontario had to wait a couple of years to be connected by means of a branch canal.) Jepson refers to the lakes and canal/s as “the nation’s first superhighways” because even though progress on the waters was limited by sail and steam to all of 4 mph it was still easier, cheaper, and faster than anything else. In other words, we are in the midst of the industrial age and the world is changing rapidly.

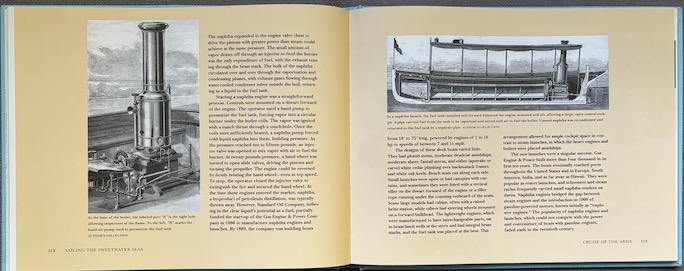

Naphtha has many uses. Used on small boats a naphtha engine is a small steam engine using naphtha fluid to power the boiler, and “vapor launches” became specifically popular in America because they were exempt from the legal requirement that any steam boat have a trained and licensed engineer on board.

That the book is written in such an approachable style surely has to do with Jepson being editorial director at McBooks Press, a Globe Pequot (publisher of this book) imprint that specializes in nautical fiction by American and British writers. Also, he founded Quarterdeck, a quarterly journal dedicated to maritime literature and art. (Incidentally, past issues of Quarterdeck are free to view at https://www.mcbooks.com)

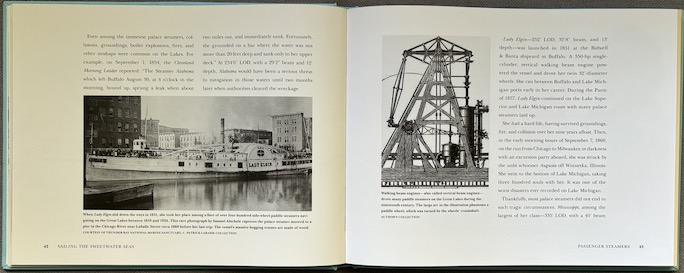

Ever seen a “walking beam engine”? They were popular on paddle wheelers like the Lady Elgin from 1851 (left page).

Relevant to this book is that before the full length of the Eerie Canal became navigable, portions of it were already in use before its opening, meaning pleasure craft and other types of small boats play a role long before the big freighters enter the picture. Both categories are presented here, the book being divided into two parts, one for “Working Vessels” and one for “Recreation.” Each spans four chapters discussing individual types. Since Jepson has a personal interest in this story his writing is about the boats as much as the people who are building, crewing, or enjoying them. In fact, he considers the writing of this book very much his own “journey of discovery” on which the reader is invited along.

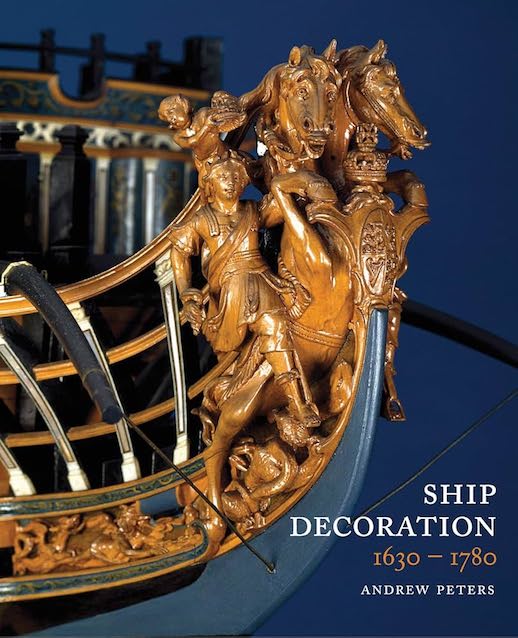

A key factor making the book different from the original magazine articles is the use of newly digitized newspaper articles and other period material. Throughout, the book showcases Michigan-based maritime artist Robert McGreevy’s work (watercolor, oil, pencil). Curators and collectors consider the ex-Chrysler man one of the “living masters” and he is a rigorous historical researcher in his own right (also museum-grade ship model builder). He too has generations-deep connections to seafaring.

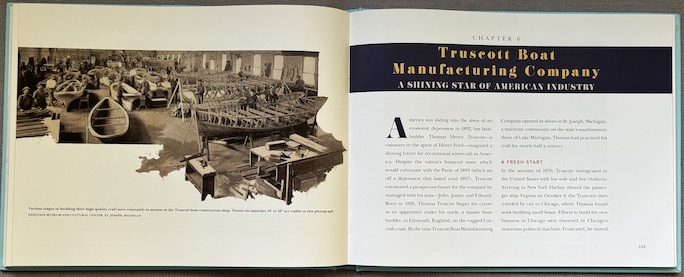

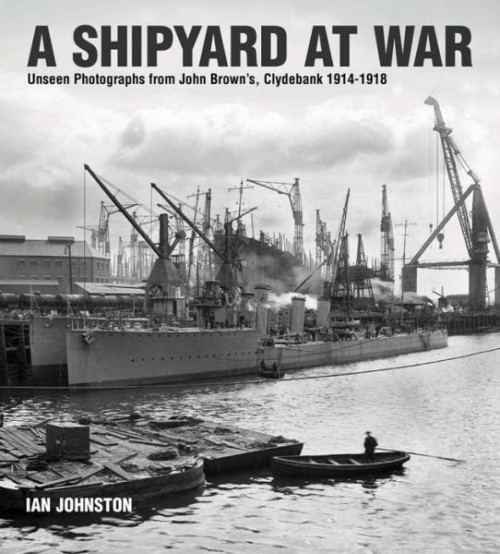

This photo is a composite showing various stages of construction.

An entire chapter, the last, is devoted to the late Henry Noyes Barkhausen (b. 1884)—Jepson interviewed him just before he turned 100—who had a lifelong interest in the history of commercial sailing vessels on the Great Lakes and cruised the northern lakes (Michigan, Huron, parts of Superior) for close to 80 years, often for a whole month at a time. In other words, he’s seen stuff . . . plus, he used to build wooden boats.

A Select Bibliography and finely parsed Index raise the bar. One can only hope the book makes the splash it deserves.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter