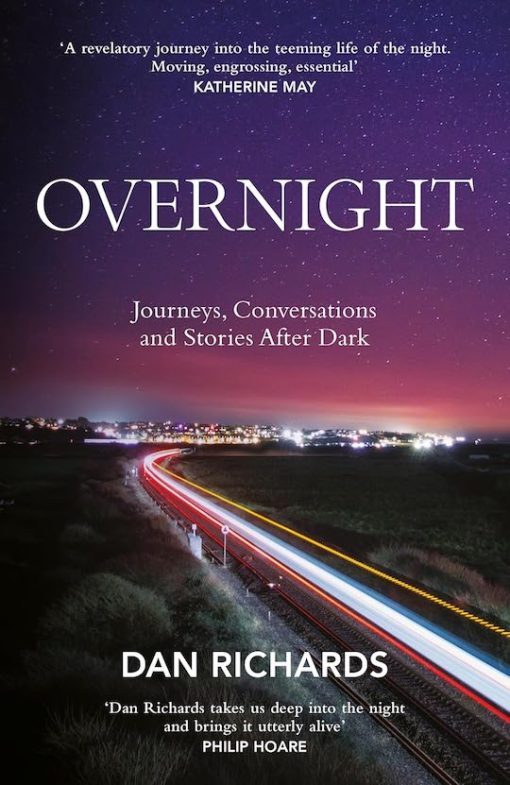

Overnight: Journeys, Conversations and Stories After Dark

by Dan Richards

by Dan Richards

“Sitting on the steps, looking down at Langham Place, I suddenly see that the soul of the book was a search for solace in dark times.”

When I was invited to review this book, I confess that my heart sank a little.

I had only known of Dan Richards as a collaborator of British nature writer Robert Macfarlane, a writer for whom my enthusiasm has declined with every new book. Macfarlane’s The Wild Places was a wonderful account of his time spent in the natural world and was rightly lauded, as was his evangelism for the sublime prose of Nan Shepherd. But with each successive book—and there have been many—Macfarlane became ever more whimsical and infuriatingly fey. Eventually I lost patience. But I have good news. Despite the fact that Dan Richards is fishing in similar waters to Mr. Macfarlane, Overnight is a literary treat which is as refreshing in style as it is satisfying in content.

This book proclaims itself as “a celebration of all things nocturnal” and its 14 chapters span night workers (cf. nurses, sailors, broadcasters), natural history, and the personal. Richards writes of Charles Dickens’ exploration of the “real desert region of the night,” as the author tried to walk off his insomnia in Victorian London. It takes prose as muscular as Dickens’ to convey the alien world we encounter after sunset, but Richards delivers. His first chapter describes the mechanical ballet that is played out every night in Southampton Docks as the super-cranes, “angle-poised on the horizon,” unload giant container ships. On a winter ferry journey between Shetland and Aberdeen the author’ s view from the bridge reveals “black marbles of the sea, crazed with foam, gianting ahead.” A description that awakened my own childhood memories of the stark elemental terror I experienced on a wild night crossing of the Irish Sea.

Speedreaders’ focus is primarily (but not exclusively) on transport and the book offers rich pickings not only on the maritime, but also the terrestrial and celestial—if helicopter search and rescue qualifies as such? The account of experiencing the centennial Vingt Quatre Heures du Mans with Porsche Penske Motorsport is a chapter to savor. Isn’t it always the case that seeing our sport through the prism of an outsider adds a perspective and insight that an insider’s myopia would never discern? The author is an automotive oxymoron—a non-driver who loves motor racing, a self-confessed “ambling flaneur.” Now there’s a status to which I can aspire. Richards watches the “deafening strobe” of the field of hypercars and “LMP2 Orecas and Alpines, Aston Martins, the crazed firecracker of the lone Nascar blaring then fading as the field disappears towards the Dunlop Chicane.” The reference to the Garage 56 Camaro triggered memories of the steamy North Carolina night I spent watching the thunderous majesty of the Bank of America 500 at Charlotte, a spectacle best enjoyed with a large, ice cold Margarita.

There’s a rich diversity of subject matter in this book, from an account of a night spent at a bakery in Dalston, in London’s hipster epicenter, to bat watching in Devon, time spent with rough sleepers in Westminster (yes, that one, with the Houses of Parliament) and reflections on the intimacy and terrors of motherhood.

There’s a rich diversity of subject matter in this book, from an account of a night spent at a bakery in Dalston, in London’s hipster epicenter, to bat watching in Devon, time spent with rough sleepers in Westminster (yes, that one, with the Houses of Parliament) and reflections on the intimacy and terrors of motherhood.

And I’ll confess I didn’t expect to encounter a chapter entitled “Moominland Midwinter,” an exploration of Finnish writer Tove Jansson’s home in the “quicksilver, sea-facing landscape” of Pellinge. Richards shares a wonderfully sage quotation about the Moomin books from Frank Cottrell-Boyce, the screenwriter and novelist. It first appeared in The Guardian newspaper (remember those?) and merits full reproduction here: “. . . it was as though Kierkegaard has come round on a playdate . . . ‘And now look, Moominpapa is taking his family off on a sailing adventure. By putting his loved ones in danger, he hopes to reawaken their sense of dependency. They are all hostages to his emotional redundancy. Ho ho ho.’” It’s hardly The Waltons is it?

The quotation that prefaces this review reveals the sense of loss and melancholy that punctuates this enchanting book. The core of Overnight is perhaps the account of the author’s near-death experience after contracting Covid 19. How long ago the early days of the pandemic seem now, lodged in a lost era when politics were almost dull (pace Trump v1.0) and conspiracy theories espoused only by crackpots and cranks. Richards recounts how he slid rapidly into the horror of being told by doctors that he was close to death, “lying in a sad twilight, dazed and exhausted.” He underwent a CT scan during his slow recovery and writes of how, as he was shown the result,“it was near impossible to reconcile the scans on the screen with my lungs, my body . . . never imagined it, this grim splotch across the scan; an invasive darkness, a lurking nightmare.” If we ever have a pantheon of Covid literature, this chapter has a place guaranteed. And forgive me, but I have to wonder: did Richards have Graham Greene’s notorious “sliver of ice in his heart” as he slid towards oblivion? Did his writer’s detachment enable him to realize there was some damned good copy to come out of all this unpleasantness?

This book deserves a wide audience, and praise from reviewers including Philip Hoare and Kassia St Clair will help it to secure one. The author is a Scot, and the book explores some subjects that seem to me quintessentially British. Two chapters epitomize this, “Night Mail” and “The Shipping Forecast”. WH Auden, the York-born poet, tapped into something at the essence of being British with—yes—Night Mail, whose rhythm replicated the sound of its subject, the train speeding north:

This is the night mail crossing the Border

Bringing the cheque and the postal order.

Richards rides the night rails too, balancing impressionism, family history, and anecdote with an account of the now vanished TPOs (travelling post offices). His descriptive prose delights. Such as this, on speeding south on a winter night: “Ahead the line scythes green. Brake lights fading in our wake, we race on, a red-crested 25,000-volt comet full of Christmas post.”

BBC radio has been broadcasting the Shipping Forecast four times daily for a century, since the dawn of the wireless age. It doesn’t matter a jot that this aural institution’s modern audience is as likely to be an insomniac as an internet-connected mariner. And the author is just as misty-eyed about the ritual of the forecast as almost every other Briton. After describing the litany of sea areas—“West, Forties, Cromarty, Forth, Northerly 4 to 6, veering north easterly”—Richards comments how you don’t even need to know what this means and how it’s a “vindication of TS Eliot’s suggestion that genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.” Neatly put.

In the 21st Century most of us have evolved to become daylight atheists. But it only takes an after-dark rustle in the woods for our inner caveman to be reawakened, vigilant, fearful, and praying for salvation. But night-time can also be the right time, and while this isn’t the place to dwell on the subtext of Joni Mitchell’s anticipation of “So much sweetness in the dark,” this book’s many musical references add nuance and color to the prose. There’s even a ten-page discography of the music that is either referenced or that “soundtracked its research, night and day.” I liked that, not least because the author has impeccable taste, with the likes of Scott Walker, Bert Jansch, and The National name-checked.

I suggest we leave the final words of this review to Bruce Springsteen (as sung, unforgettably by Patti Smith):

“Because the Night” . . .

Copyright John Aston, 2025 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter