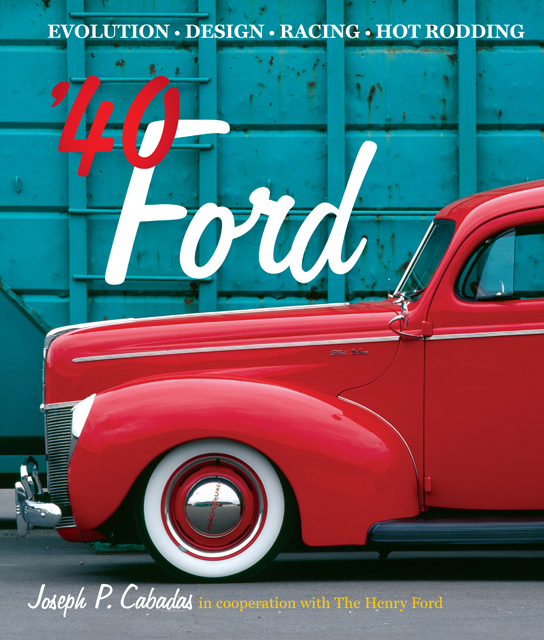

‘40 Ford: Evolution, Design, Racing, Hot Rodding

by Joseph P. Cabadas

by Joseph P. Cabadas

One can only wish that readers don’t pass this book by, thinking it’s about a model—iconic as it is—or a marque, or a period they’re not really interested in. There’s a whole lot more to this book, which is no surprise if you consider it in the context of the author’s previous work.

Already in its own time, the 1940 Ford looked good. Also no surprise, if you consider that it and its predecessors were influenced by the trend-setting 1936 Lincoln-Zephyr, the one car the Museum of Modern Art pronounced “the first successfully designed streamlined car in America.”

If you talk about the Zephyr you talk about the Sterkenberg (the what now?), and about the shift from outsourced to in-house design. And if you let the ole grey matter percolate a bit and think of the calendar, you realize these are the days of internecine warfare at Ford—strife between father Henry and son Edsel, knuckle-busting “Cast Iron” Charlie Sorensen terrorizing the employees, or Ford’s internal secret police under Harry Bennett—and war in the wider world: unions, the Big 3, WWII. This too is the story told here.

And auto historian Joe Cabadas is just the man to do it. He grappled with the Big Picture in his The American Auto Factory (2003) and River Rouge: Ford’s Industrial Colossus (2005) and both the research he did for those books and the contacts he made lend themselves to spawning books on ancillary topics. One such contact was Ross Cousins who joined Ford in 1938 as an illustrator and was the last surviving member (d. 2010) of Bob Gregoire’s design staff. Edsel’s genius—yes, we call it that—in tapping Gregoire to design a European-influenced roadster and then installing him as head of the newly founded Design Department are key factors in the success of the car at the core of this book.

Much of the material here comes from the seemingly endless holdings of The Henry Ford, home to over 26 million artifacts pertaining to American History, specifically the Benson Ford Research Center that is the custodian of the Ford Motor Company’s and other historical automotive records. In the context of all of the above, Cabadas threads the needle with a mini-history of the Models T (successful) and A (not so much). Looking at the design idiom of the time, he describes what is new and noteworthy about the ’40 Ford, the compromises between design and manufacturing reality, cost, construction, and the place of the model in the marketplace. Much useful reference is made to competitors’ product, with particular focus on their use of V8 engines and also the input of/influence from Ford’s European operation.

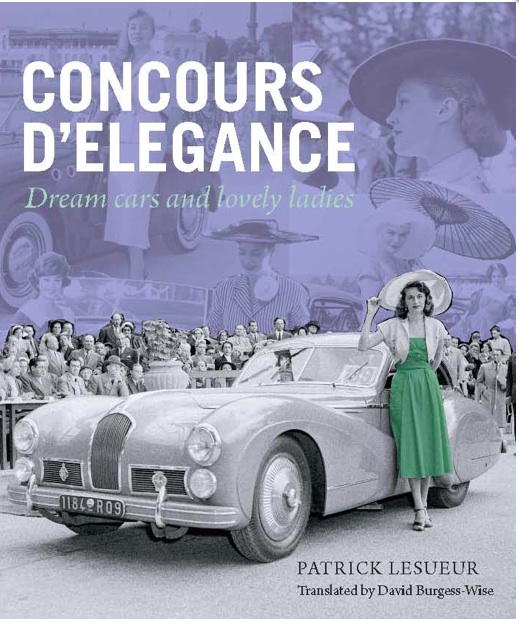

All the various body styles are covered but the story being told in chronological order has the unhappy side effect that the somewhat more specialized reader who wants to look up specific things about specific variants, say commercial trucks or woodies, will not find them conveniently in one chapter but scattered throughout. The Table of Contents is of little help here, as is the Index which, while thorough, requires of the reader a certain degree of pre-knowledge to even look in the right spot. A host of sidebars dispense information about anything from car colors to leaf springs to the Village Industries. A short closing chapter covers racing: the Miller-Fords at Indy, Monte Carlo, the Ford/Chevy tug of war in South America, stock cars, and dry lakes. The final few pages give just the briefest of glimpses into the hot rod career of the ’40 Ford and shows five examples of restored rods.

All through the rest of the book the illustrations are vintage, and mostly b/w. In addition to the many photos there are also ads (even from England and France), race programs, and coachwork drawings etc. An extensive, multi-page Bibliography will provide leads to years worth of further reading.

So, far more than just a book about one particular Ford, this is a multi-faceted look at an important and colorful chapter in American automaking. “Entertaining” is a word the author uses several times as one of reactions he hopes the book will elicit. And it will; the narrative is fluid and at no point gets bogged down in technical jargon, specs, or other sort of minutia. (Not that that wouldn’t be entertaining for some!) The entertainment quotient is boosted by the book’s intelligent design. Good design can’t save a bad book but it can make a good book better. Period-sympathetic colors and typography and good visual organization coupled with nice paper and faultless photo reproduction make such a well-rounded, competent package that the low price of $35 looks like a mistake.

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter