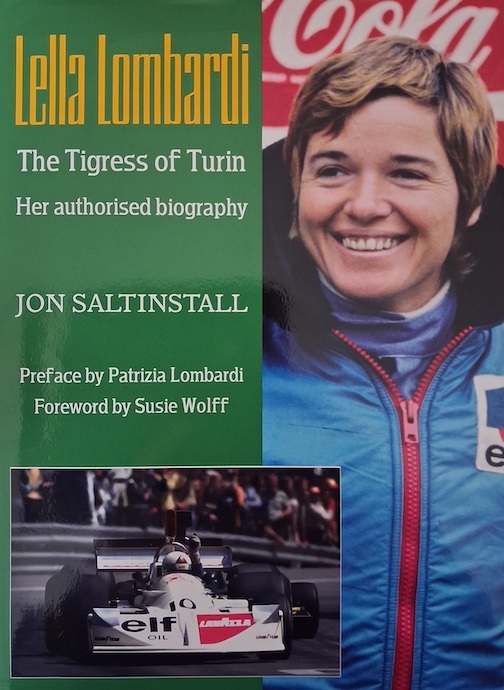

Lella Lombardi – The Tigress of Turin, Her Authorised Biography

by Jon Saltinstall

by Jon Saltinstall

“Several recurring themes have emerged while researching this book, but one of the most striking is that nobody I interviewed or who spoke about her in contemporary accounts had a bad word to say about Lella.”

It is the fate of some race drivers to be defined by a single moment. David Purley is remembered for his heroism in trying to rescue Roger Williamson from his burning March 731 at Zandvoort, when the rest of the field had developed selective myopia. Vittorio Brambilla is celebrated for having crashed into the Armco seconds after winning the rainy Austrian Grand Prix in 1975. And Maria Grazia “Lella” Lombardi’s fame derives from the fact that she’s the only woman to have scored in the World Drivers’ Championship. It was, in fact, only half a point because the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix was stopped before 60% race distance had elapsed. But this was in an era when points were only awarded down to sixth place, and grids were much bigger than today. Every student of Formula One history knows Lella’s name, but her career comprised so much more than those 29 laps at Montjuic Park, Barcelona.

And now Jon Saltinstall has told her story. He is well equipped to do so, having written award-winning books on the careers of Lella’s more famous contemporaries, Jacky Ickx and Niki Lauda. This 320-page book will stand as the first and probably the last word on the life and career of “the butcher’s girl from Frugarolo” who was later dubbed “the Tigress of Turin” by Brands Hatch supremo John Webb. And who cared that she lived over an hour’s drive away from Turin?

Born in 1941, Lombardi showed an empathy with powered transport from childhood. She was driving by 13, loved to race scooters and by 1959 had become “the fastest salami truck driver in Turin,” honing her skills on the roads of the Ligurian Riviera. The author describes how his subject grew into a charismatic and confident young woman, with a wide circle of friends who shared her love of dancing and sheer joie de vivre. A surprise for those who might have formed a different impression from the images of the demure and serious-looking young woman which appeared in the racing press.

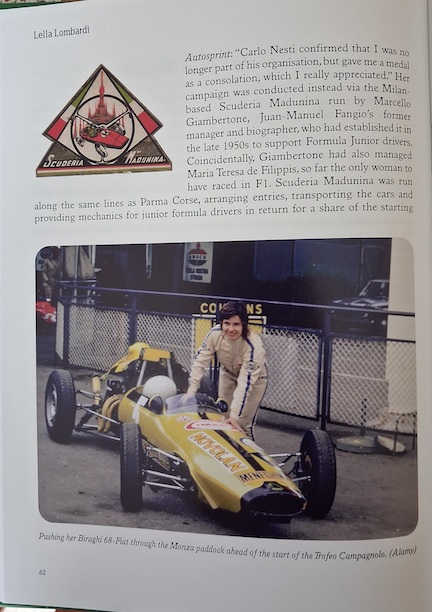

Biraghi 68 Fiat 850.

Saltinstall has had plenty of practice in researching drivers’ competition histories, and this book includes a 17-page appendix detailing every event its subject contested. It’s a reminder of just how vibrant the European racing scene was in the Sixties and Seventies, and Lella’s early career epitomized the trajectory taken by many of her peers. Early experience in small single seaters—F850/875, Formula Ford, and F3—was punctuated by races and hill climbs in sundry touring cars—Alfa Romeo GTA, Lancia Fulvia HF, and Ford Escort Mexico. It’s an insight into a lost world where even a modest budget allowed young drivers to race almost weekly. It’s a contrast to the ruinously expensive straitjacket of contemporary single-seater racing. In every respect apart from her gender, Lella’s early racing career was typical, as I was reminded by the names I had once read about in Autosportlong ago. Drivers such as the Brambilla brothers (Lella often shared drives with Vittorio), Giancarlo Naddeo, and Maurizio Flammini are some of the many names I either read about in period or even saw compete in the bigger Formula 3 events. And with no disrespect to good Anglo-Saxon racers like Barrie Maskell, Syd Fox, Bev Bond and (yes) Nigel Mansell, aren’t Italian surnames so gorgeously mellifluous, so damned sexy?

Enter John Webb, who had witnessed Lella’s potential in the 1973 Monaco F3 race. She had outpaced such names as Tony Brise, Alan Jones and “Kentucky Kid” Danny Sullivan. Always a champion of women drivers, Webb secured her entry into the high profile Shellsport Escort Mexico Celebrity Series. Firmly in “The Past is Another Country” category fall Sue Baker’s program notes, previewing the Mexico feud between “Farmer’s wife/rally driver/racing driver Gill Fortescue Thomas . . . and Lella Lombardi. It will be interesting to see who is quicker—our freckle-faced blonde British queen of the racetrack, or Italy’s crop-haired brunette. I am sorry to say my money is on the Italian.” Am I alone in thinking there’s more than a whiff of something spiteful in that PR fluff?

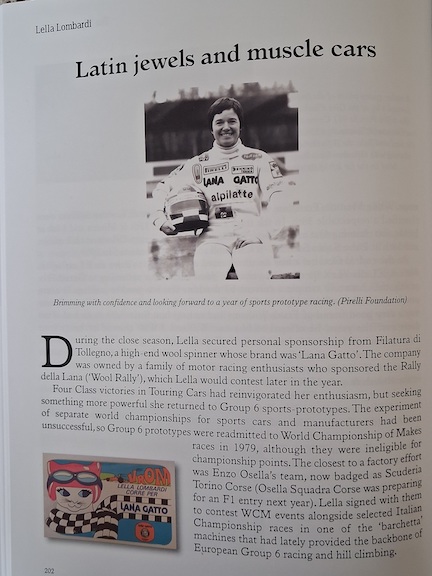

The brunette did her talking on track, and she was soon wrestling Formula 5000 cars around tracks in Europe, the USA, and Australia. The thunderous stock block Chevy V8 single-seaters were arguably the most brutally macho racers of all—big wings, big slicks, no power steering, and 500 bhp. And yet the young woman from Frugarolo proved herself capable of toughing it out with the likes of hard racers such as Damien “Mad Dog” Magee, Bob Evans, and Kevin Bartlett. As fellow Italian Mario Andretti succinctly put it, “The only difference between her and anyone else out there is she doesn’t have any balls.” In the anatomical, not metaphorical sense.

The brunette did her talking on track, and she was soon wrestling Formula 5000 cars around tracks in Europe, the USA, and Australia. The thunderous stock block Chevy V8 single-seaters were arguably the most brutally macho racers of all—big wings, big slicks, no power steering, and 500 bhp. And yet the young woman from Frugarolo proved herself capable of toughing it out with the likes of hard racers such as Damien “Mad Dog” Magee, Bob Evans, and Kevin Bartlett. As fellow Italian Mario Andretti succinctly put it, “The only difference between her and anyone else out there is she doesn’t have any balls.” In the anatomical, not metaphorical sense.

Formula One now occupies its own ecosystem, a billion-dollar sport with a fanbase often uninterested in, or even dismissive of, other motorsport. I confess to having had some concern that, for marketing reasons alone, the book would place undue emphasis on Lombardi’s short F1 career. But I needn’t have worried, and it is to the author and publisher’s credit that, although her Grand Prix career is diligently recorded, it is not given undue emphasis and does not unbalance the story of a long career. She came (with help from Count Gughi Zanon), she saw (a March 751 with an iffy chassis) and while she didn’t conquer, it is to her everlasting credit that she made it at all.

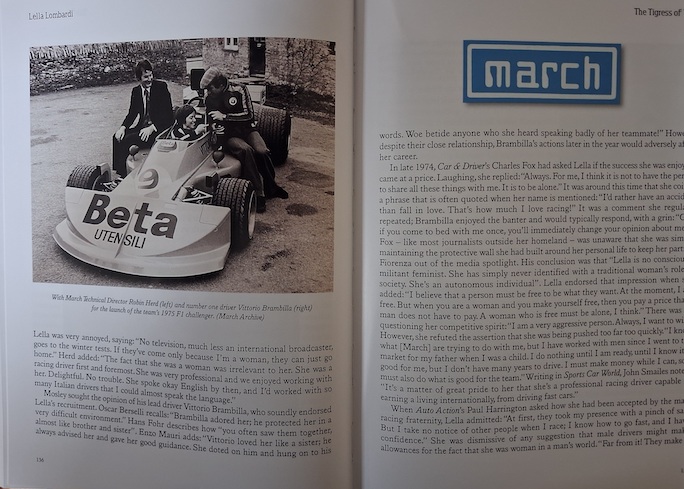

Lella in March 751 with Vittorio Brambilla and Robin Herd.

Sex and sexuality are not the usual fare in books about motorsport, but both are covered here, and this is why. The Sixties and Seventies are often dismissed as an era of rampant sexism by cultural commentators who weren’t even alive at the time. But the truth was more nuanced. Women were often objectified, patronized and dismissed, if not excluded, but those caveman attitudes were also underpinned by a laissez faire culture where virtually nothing was taken very seriously. We might have lived in the shadow of the Cold War, but there was an easy-going, tolerant, and optimistic vibe too. Formula One is now as depressingly tribal as ball games, and social media is inflamed by every minor slight (real or imagined) or on-track incident. But in 1975, only the Ferrari tifosi hinted at the toxic fandom we now endure. And where women racers are concerned, in 2025 they are no sooner freighted with unrealistic expectation than they are sneered at and dismissed, thanks to a toxic misogyny that simply didn’t exist fifty years ago. I saw Lella race many times, and not once did I hear her (or her peers Divina Galica or Desiré Wilson) being dismissed as being unworthy of even taking part. Dinosaurs like Graham Hill, Bobby Unser, and Denis Jenkinson spouted their nonsense, as the author notes, but consider baby boomer Niki Lauda’s words: “A woman has the same ability as a man . . . why shouldn’t she drive?”

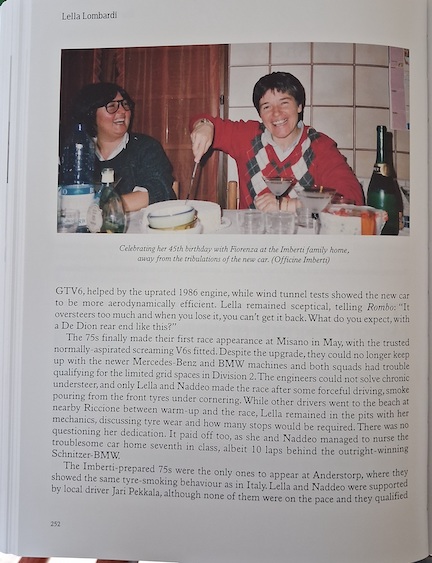

Lella’s 45th birthday with partner Fiorenza.

As for sexual orientation, it simply wasn’t talked about. Lella was openly gay, in a long-term relationship with her partner Fiorenza [1], who often accompanied her to races. Like my fellow enthusiasts of the time, I neither knew nor cared about her private life, those being the simpler times when even an F1 driver had such a luxury. In his recent book Alex Jacques referred to the fact that Lella was a member of the LGBTQ+ community, apparently unaware that such a community didn’t even exist at the time. No fault of Gen Y Alex, but it epitomizes how poor a fit modern societal norms can be on past times. The author writes about Lella’s private life because it’s part of her story but he takes care to ensure that it doesn’t, and shouldn’t, define her.

Lella Lombardi died of breast cancer in 1992, aged 51, and Fiorenza died a year later from the same cause. Lella had enjoyed a successful post-F1 career, with myriad sports and touring car successes, both as driver and team owner. She is rightly celebrated in her home country and I am delighted that her story has now so comprehensively been told in this book. The words are complemented by a wealth of images and I was especially taken with the reproductions of now-forgotten race team logos and stickers.

Jon Saltinstall should have the last word: “Lella Lombardi’s significance to motor sport is far greater than that half-point in the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix.”

- Looking for a party game? Try discovering Fiorenza’s surname. Even people who knew the couple well weren’t told, to protect her privacy.

Copyright 2025, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter