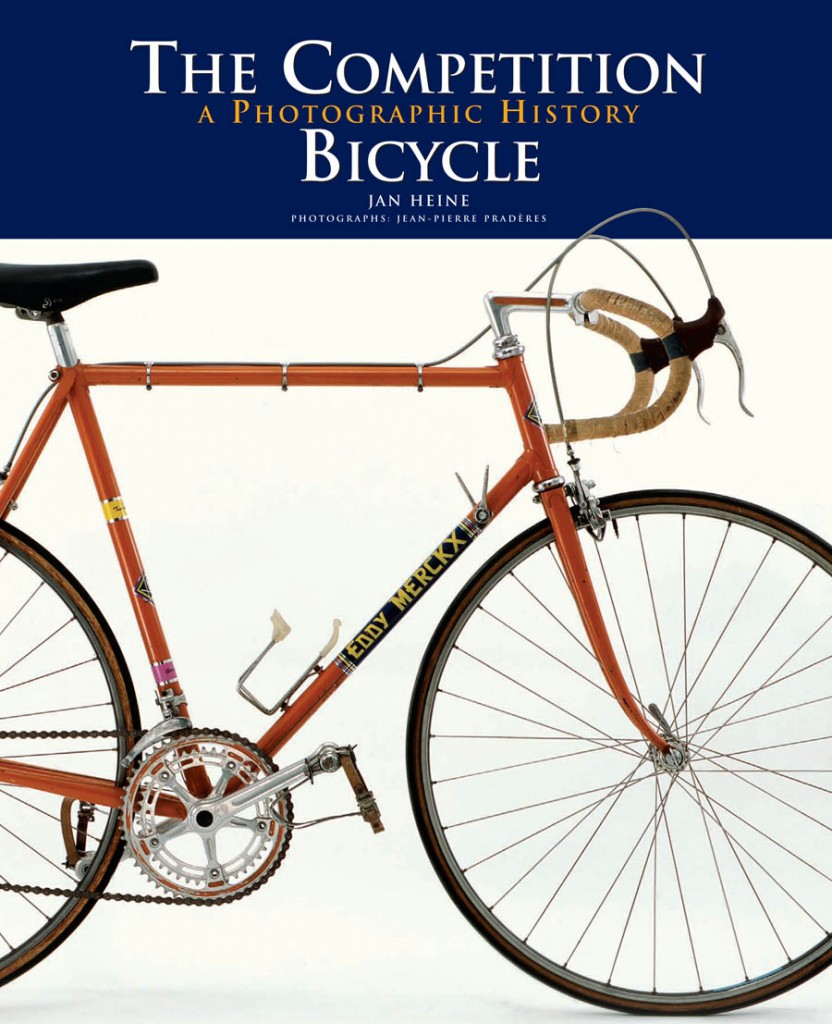

The Competition Bicycle: A Photographic History

by Jan Heine (text) & Jean-Pierre Pradères (photos)

by Jan Heine (text) & Jean-Pierre Pradères (photos)

Three years after giving us The Golden Age of Handbuilt Bicycles, the same author and photographer have teamed up to present a similar opus on hand-built special-purpose bicycles from 1880 to 1994. Obviously, bicyclists will want to know about this book. But so should anyone who rides or drives anything, who has an interest in mechanical workings, or who appreciates the beauty of shaped metal.

Bicycles, especially lean competition bikes, are the quintessential expression of the form-follows-function school of thought since their motive power derives solely from relatively feeble human effort. Lighter = faster = easier.

Even though the new book has a more narrow focus it may well be the one with broader appeal because this time the bikes are not just French but Western European makes in general and also American. At first, and even at second glance, the books go about their business in similar manner but there are some noteworthy differences in terms of user-friendliness. The common denominator is certainly the supremely excellent studio photography by Jean-Pierre Pradères.

You may recognize his name from the motorcycle world to which he has contributed photos for over 25 years. Aside from the obvious prerequisite of possessing sophisticated technical skills, he has the sort of eye and affinity for the subject matter that draws out the bikes’ inner workings. Shot against a uniform, light grey backdrop there are the expected, necessary, and useful close-ups but then there are also unexpected, adventurous angles such as one from below straight up into the cranks and chain. This is not random art for art’s sake but to illustrate a pertinent point. The bikes, incidentally, are in unrestored original condition. This book covers only 34 bikes in about the same space as the earlier book’s 50 so there are rather more photos of any one bike.

Author Heine is not only editor of Bicycle Quarterly (published by Bicycle Quarterly Press which he founded in 2002) but he also rides competitively. He has done the 770-mile Paris-Brest-Paris long-distance race three times and in 2003 ran the fastest mixed tandem on a 1948 René Herse. Both his day job and his leisure pursuits thus give him an uncommon degree of involvement with the things he writes about. A good number of the bikes presented here aren’t just generic racing bikes but the mounts of specific people in specific events. Heine realizes the difficulties with such claims of provenance and he also knows the vast number of fakes on the market these days. He says that quite a few were dropped from the book after being photographed because the research didn’t hold up and he feels confident that “most” of the bikes he and his collaborators and reviewers settled on “are what they purport to be.” Since this is not an authenticity or value guide, this issue is really only peripheral to the overall story of the evolution of the competition (board, road, mountain, touring) bike anyway. The book has, again, no Table of Contents and begins instead with a visual index that shows thumbnail scale photos of all 34 bikes with maker’s name, rider (if applicable), and year/era.

Bike builders/restorers will appreciate a new feature in this book: the bikes are shown in the same order at the back of the book but this time as line art, again to scale, and with dimensions given. This greatly facilitates comparisons, also helped by the fact that all are pointing in the same direction (right), unlike the Index which is inexplicably random in that 31 point right and 3 left. Also provided are key specs, but not in a uniform manner, and non-original parts or features are identified. What is missing, in either section is something surely most readers would find useful: country of manufacture. For that you have to sift through the text or deduce it from photos of the makers’ plates.

Another organizational oddity is that the page numbers shown in the Index lead to pages that have useful, descriptive “chapter” titles but don’t begin with or prominently show the bike info. This information is particularly missed when one section/chapter covers more than one bike and the reader who simply turns the page needs to read a few sentences before realizing that now a different bike is featured. Most often the bike info can be found in the photo captions or occasionally the running head. The reader who is new to all this and relies on such guidance is not well catered for! The designer of this and the previous book is the same, Christophe Courbou; those who expect book design to serve a didactic purpose will be unimpressed.

Heine’s lively text talks about the rider and event, the maker, and the bikes’ defining features. There is minimal jargon (and no glossary) but readers new to the subject would do well to familiarize themselves with the lingo. Pradères photos are supplemented with archival photos, ads, and ephemera. Printing, paper, photo reproduction, and binding (look under the dust jacket!) are most becoming. Whether you are a dyed in the wool bicyclist or just starting out you will find much of interest in this colorful picture of a rich history from old-timey “high wheeler” to modern-day wind tunnel-tested carbon fiber lightweight.

Signed copies are available from the publisher for an extra $5. Also available in German as Die Räder der Sieger by Covandonga Publishing.

Copyright 2011, Charly Baumann/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter