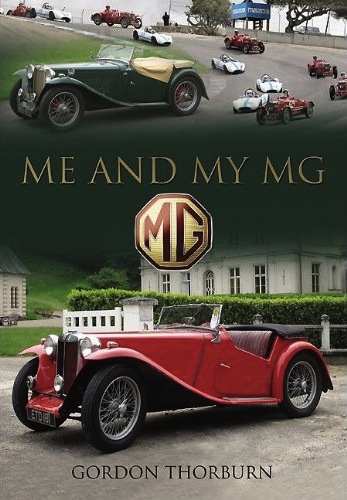

Me and My MG: Stories from MG Owners Around the World

Elementary, dear Watson—this is a book about MGs. But, “MG” is used here in a prototypal sense, as a placeholder for friendly low-tech as opposed to evil high-tech. Or, in Thorburn’s words, “proper cars” versus “gigahertzly complex . . . computerized heaps of tin” that have no soul, quirks, personality, or redeeming virtues except permitting joyless motoring from A to B. Old cars, he opines, have character, and their foibles, in turn, build character in their owners. Well . . .

The reason the MG became the hook from which to hang this story is that “of all the cars in all the world, [it is] the one with the greatest number of enthusiasts, clubs, events, and so on.” Well . . .

Thorburn’s introductory chapter is basically a lament—see above—and highlights key moments in the history of the internal combustion engine since Genghis Khan in whose cannon Thorburn sees the IC principle at work. (Well . . .)

Even Thorburn beginning the book with the scene from Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 children’s classic The Wind in the Willows in which Mr. Toad encounters his first motorcar (“. . . with a blast of wind and a whirl of sound that made them jump for the nearest ditch. It was on them!”) are so lopsidedly retro that one is often left wondering if the time warp Thorburn claims as his natural domain is for real or if he’s merely piling on the rhetoric for effect. Except for reeling off a few of his other published works (cf. gypsy caravans, pubs, herb gardens, a police dog, an almost cult-status book about sheds), this book does not say much else about him. A reader who knew that Thorburn was a professional infinitive-splitter in the advertising world would realize that cooking up good copy to get a rise out of people is just his thing. Already a decade before publishing this MG book, he left a voluminous paper trail of rants against “technological warfare” (in 1993 he recalled VW introducing fuel gauges on their cars—to him, a sure sign that the sky was falling—and wrote “. . . [it] began for me not with the fuel gauge but with the automatic choke of a Sierra estate.”). Let’s assume he means what he says—and just leave it at that. One problem, though: a writer with very strong opinions may find it difficult to keep a lid on them when he handles other people’s material. This book, for instance, consists of 30-odd individual vignettes that their writers submitted to Thorburn who then rewrote/recast/adapted them. And so all the stories end up advancing various facets of Thorburn’s themes, possibly in ways or to degrees the original writers hadn’t necessarily intended. At least one of them feels just that way.

What all this means is that you need to factor in the author’s “spin” when you read the owner histories. They range from one to several pages, are in no discernable order as to age of car or owner, and in and of themselves have no common theme other than to capture random reminiscences of the kind you’d expect to hear during an afternoon of tire kicking and shoulder slapping at a car club event. Interesting to some, possibly tedious to others. If you had/have/will have an MG you’ll clearly want to partake of these experiences and, really, any owner of any sort of not-so-new car (especially a British make) will commiserate. Another thing most of the stories have in common is the notion that it is the people more than the cars that are the heart of the old-car movement.

So, be it the small boy who graduated from assembling plastic kits to a lasting love for full-size MGs, or a father and son bonding over their respective MGs, and mortgaging the house or postponing marriage in order to buy that MG, there’s a little bit of everything. Mishaps are a recurring theme, so are restorations. The cars described range from blue-blood rarity to mass-market MGB. Given Thorburn’s take on the world it should come as no surprise that all but one of the MGs featured here are pre-1980, the year the Abingdon factory closed and MG production ceased. (The marque was revived in spirit and in practice several times since and exists still today under the umbrella of Chinese government-owned SAIC Group.)

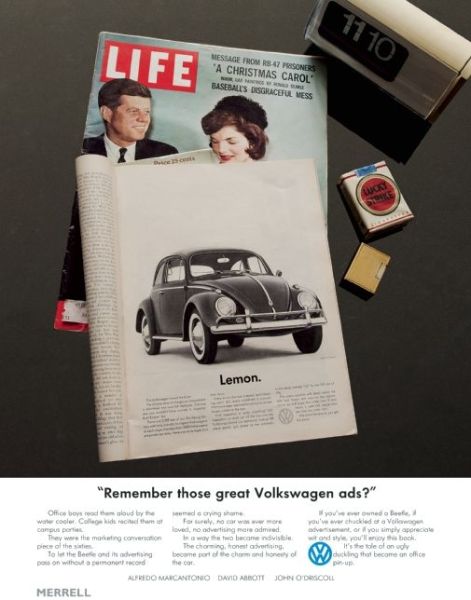

Being supplied by the various writers, the photos have a certain uncurated air about them. They are snaps, no more no less. Since Thorburn is not an MG specialist, the photo captions are rather on the vague side. What little specificity they possess is mostly in relation to the people in them—which is probably of no interest to anyone except the people in them. Also shown are a number of postage stamps featuring MGs and several period ads.

One eccentricity is unusual enough to be worth noting: the story about a Belgian professor’s MG has long sections in French, then rendered in English translation. Cleverness? Affectation? Humor? If this were a movie pitch we’d say, “Think Garrison Keillor meets Jeremy Clarkson.” (For readers with other cultural reference points, it merely means be ready for a good dose of pomposity and plain hot air.)

Copyright 2012, Charly Baumann (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter