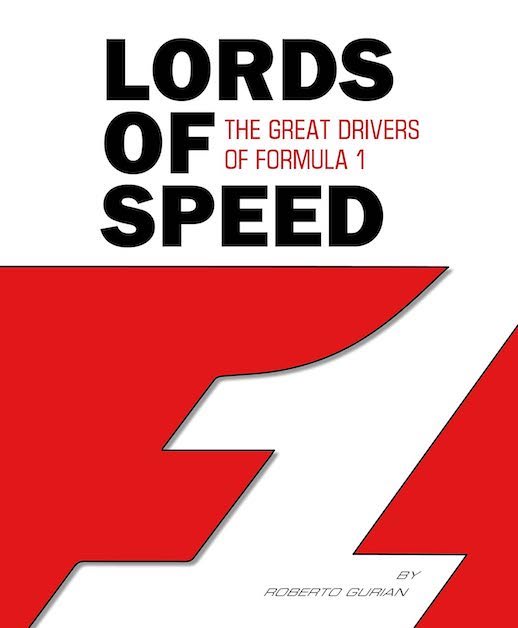

A.T.S., The Italian Team That Challenged Ferrari

by Michael John Lazzari

by Michael John Lazzari

At the end of October 1961, eight members of the Ferrari staff quit. Their resignations centered around a number of issues, real or perceived, regarding their ability to perform their work at Ferrari. One of these, perhaps the tipping point, was the constant interference of Enzo’s wife Laura with the operations of the racing team and other aspects of life at the Ferrari factory. Already a highly volatile—perhaps even medieval in some respects—workplace, this was even more so with the Ferrari racing team, Scuderia Ferrari. Of the eight, three relented, apologized, and meekly returned to the fold, albeit in rather reduced circumstances, the demotions being due to the intemperate act of disloyalty.

As for the others, after a short period of unemployment and wondering as to what was next, they all ended up back in the racing business, this being thanks to the formation of Automobili Turismo Sport Serenissima, ATS, in February 1962; the Serenissima part of the company name would later be dropped. The new company set out to develop a Grand Prix machine and a Grand Touring car to compete against their former employer. With Carlo Chiti and Romolo Tavoni, former race engineer and team manager for Ferrari, respectively, as part of the new ATS operation, some measure of success was expected, since, after all, they had help win the world championship for Ferrari in 1961. They would challenge Ferrari on the track and, hopefully, bring success to both the company, ATS, and the city of Bologna.

It did not quite work out that way, of course.

The ATS Tipo 100 appeared in only five events during the 1963 season: the Belgian, Dutch, Italian, United States, and Mexican Grands Prix. The transporter had a wreck on its way to the German Grand Prix, with the result that the cars were unable to participate. Former Ferrari drivers Giancarlo Baghetti and Phil Hill, the 1961 world champion, managed only to finish only two races the entire season: Hill placing 11th and Baghetti 15th at the Italian Grand Prix at Monza—being, ironically, the only Italian cars at the finish when the Ferraris of John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini dropped out of the race. As for the other events, it was one thing after another breaking, often depriving the team of even some modest level of accomplishment among the backmarkers. The team folded after the 1963 season.

The effort to build and race GT cars went little better, even if one made it onto the cover of the September 1964 issue Road & Track magazine: depicting a ATS GTS at the Targa Florio.

Then, for all the usual and infinite number of reasons associated with hopes and ambition far exceeding the available funding, it all ended. Badly.

The English edition of this book comes after the original, Italian edition (ATS, la scuderia bolognese che sfidò Ferrari) went through two printings. This suggests that there was sufficient interest in the tale of this generally forgotten marque whose presence during the 1963 season tended to be the fodder for cruel jokes and caustic asides by those commenting on the racing scene. That someone took the time and effort to track down many of those involved in the ATS debacle and interview them is noteworthy. That ATS almost ended or severely affected the careers of many of those involved would alone make it a fascinating story.

Unfortunately, the English translation by Patricia Ann Williams is such that any chance of reading it with any degree of coherence and clarity is nearly impossible. It does make one begin to truly appreciate the difficulties and challenges of translating material such as this. It definitely makes one admire all the more those translations that retain the flow and clarity of the original.

Anyone familiar with different languages recognizes that it is often the nuances and subtleties and not only the technical jargon that make or break the transformation of a text. Graduate studies in the humanities often discover this the hard way when they begin to realize that their translations of various texts miss such nuances and that, while generally literal, their translations are often not as literate as one would wish.

Had the translation been better, it would be far easier to judge the contents of the book on its merits, or lack thereof, rather than attempt to make sense of some truly tortured syntax and often quizzical or odd terms, such as realizing that the failure of the “propeller” was actually that of the engine failing. However, given what one is presented, it is difficult to recommend this book, even to those interested in this esoteric topic.

The story of ATS certainly deserves better—at least in English. (Despite his English-sounding first name/s, author Lazzari is a native Italian [b. 1970]; he is a professional journalist and broadcaster and has worked for several newspapers and published, among others, several other motorsports books such as Eroi al volante, trenta storie di piloti oltre la leggenda (about F1, published by Castelvecchi) and Teodoro Zeccoli: Cuore Alfa (about Alfa Romeo, published by Maglio.)

Copyright 2016, Don Capps (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter