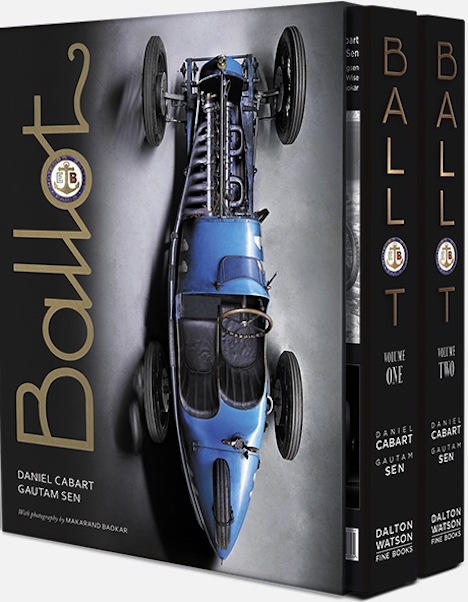

Ballot

by Daniel Cabart and Gautam Sen

by Daniel Cabart and Gautam Sen

The Ballot bible, then. Two hefty volumes, gold-embossed and slipcased, each containing texts by a clutch of distinguished apostles relating overlapping aspects of an extraordinary tale.

The two Ernests at its heart, Ballot and Henry, are enigmatic figures both. Vain, authoritarian and as secretive as his name implies, the Svengali-like Monsieur Ballot emerges as a canny operator who, having learned basic engineering in the French navy in his early twenties, honed his skills at Phébus and Prunel from 1894 to 1904, when he first established his eponymous firm to build proprietary engines. As the first volume begins by explaining, so aggressively did Ballot diversify into powerplants of every type and all sizes from 1 hp to 150 for every conceivable application that before World War I the company could claim to be the largest of its type in France, with global reach. Backed by big investors, he was already a multimillionaire with a smart new factory in the Boulevard Brune with which to capitalize on the subsequent demand for military matériel (including hundreds of Hispano-Suiza aero engines). Post-armistice, having cemented a reputation for building reliable and reassuringly expensive engines, he was therefore well placed to enter the limelight with glamorous cars bearing his own name.

The catalyst in this enterprise, Ernest Henry, was famously the subject of long-running controversy, embroiling all the heavyweight motoring pundits of the last century: Bradley, Borgeson, Karslake, Sedgwick, Pomeroy, Boddy. None denied the archetypal status of the twin ohc, four valves-per-cylinder dual-ignition racing engines pioneered by Peugeot in 1912 and 1913. But some charged that far from being their creator, Henry was merely a good draughtsman who passed off pilfered Hispano-Suiza plans, thereby robbing the dead Paolo Zuccarelli of his due credit. Even in an era of widespread design plagiarism, this was scandalous stuff.

Rudy Henry duly traces his grandfather’s career, from his first job in 1906 with Lucien and Charles Picker, making L- and T-head fours for powerboat racing and Lucia cars. Like the Pickers, Henry graduated from Geneva’s Technicum Institut, a formidable talent incubator whose alumni also numbered Marc Birkigt, Georges Roesch, and the Dufaux brothers. Thence to France with Charles Picker to develop the influential Labor-Picker aero engine, whose basic architecture resembled Henry’s revolutionary 1912 Peugeot unit in everything bar the head. We are told that Zuccarelli chose Henry rather than Picker to join him, Georges Boillot (then Robert Peugeot’s chauffeur) and Jules Goux in Peugeot’s hungry new racing division in 1911 because he knew of Henry’s advanced four-valve dohc concept.

Despite the deserved triumphs of the resulting ultra-efficient and much copied Peugeots against their elephantine opponents, Henry’s abrupt dismissal from the Sochaux firm in 1915 was followed by a stint at Bariquand & Marre to work on a 200 hp aero engine eventually rejected by the military in favour of Peugeot’s similar quad-cam V8, ironically elaborated from his own proposals. By the time he was introduced to Ballot by René Thomas in December 1918, Henry had already drawn up a low, narrow, short stroke 4.8L dohc racing straight eight with bucket cam followers—a brilliant basis for projecting Ballot into the upper echelons of international competition. Although built in record time and in paranoid secrecy, the cars proved the fastest around Indianapolis in 1919, only to be repeatedly denied race honours through bungled preparation.

October 1920 saw the launch of Henry’s swansong at Ballot, and the true star of this book: the epic 2LS. Essentially a four-pot version of the eight with the ohc driven by shaft instead of gears, this exquisitely engineered, prohibitively costly and invariably dashingly clad sports racer “of surpassing versatility” remains the keystone of the marque’s reputation.

Late in 1921, Henry left for an unhappy period under Louis Coatalen at STD working on the ill-fated 2-litre twin-cam Sunbeam for the 1922 Strasbourg GP, effectively a clone of the 1914 Coupe de l’Auto Peugeot. After penning a twin-cam engine for Oméga Six to contest the 1924 Le Mans event (not Maurice Gadoux’s touring model, as the text implies), Henry spent the rest of his career in the more prosaic world of piston manufacture.

A deft exegesis of Ballot’s racing engines and their antecedents by Karl Ludvigsen comes complete with an extended riff on the history of racing straight eights. This is complemented by a lavishly illustrated 100-page description of the races contested by Henry-engined cars, and Volume 1 concludes with a detailed chassis-by-chassis history of Ballot racing cars by David Burgess-Wise and Douglas Blain’s forensic account of the surviving 2LS cars and components, a palimpsest of the eight-part series of articles they produced for The Automobile in 2012.

Volume 2 majors on the road cars, beginning with a technical description of the bread-and-butter 2LT. Although blithely promoted by the company as the 2-liter to exploit the halo effect of the magisterial 2LS, the 2LT was an altogether more humdrum machine. Homologated in 1922 and powered by a conventional ohc four-cylinder designed by ex-Panhard engineer Louis Germain and Fernand Vadier, the 2LT initially suffered from a weak three-bearing crank and chassis. The 2LTS of 1925 improved matters, with a new head sporting recessed combustion chambers and inclined valves. Contracts with Vanvooren and Figoni also allowed the company to offer complete cars for the first time.

Although the 2LT sold well enough for some 2000 to find owners between 1923 and 1929, the range was supplemented by two flops: a short-lived six-cylinder 2L ohc in 1926, and in 1927, the gutless RH straight eight on the long 2LTS chassis, underdeveloped and plagued by lubrication and cooling troubles. Not having consulted his board on commissioning these models, the autocratic Ballot was sacked; although dubbed the Ballot HR-26, the last cars to roll out of boulevard Brune in 1933 weren’t Ballots at all but Hispano Juniors. Notwithstanding, an ugly Ballot was a rarity, and here the description of each model is followed by imaginatively curated sample of chic coachwork on the chassis concerned, including some hen’s teeth rarities (Esclapez of Oran, anyone?).

There follows a fascinating exploration of the bewildering diversity of Ballot engines from 1904 to 1928 and their manifold uses—not only by automobile manufacturers large (most notably, Delage from 1909 to 1915) and very small, but in marine, agricultural, and industrial applications. Apart from sound engineering, the brand’s shtick was to supply turnkey ensembles, complete with accessories and transmission, and engines bearing Ballot’s anchor motif were trusted throughout Europe and well beyond. Then, bizarrely, we return to maestro Ludvigsen for lengthy disquisition on the inheritors of Henry’s legacy, with particular reference to Harry Miller, Coatalen’s STD combine, Duesenberg, and Ettore Bugatti. The second volume concludes with copious appendices as to Ballot’s complete racing record, period magazine articles and road tests, owners’ testimonies, official homologation documents, sales catalogs, press ads, and a full index.

Lamentations? A few, but minor. In both volumes, the contemporary photographs of both racing and touring cars, the distinctive factory and the kaleidoscope of Ballot-engined machines, are compendious and of generally fine quality. Integrating such period iconography with modern digital color images (as artful and moody as these are) is problematic with all such books, but the random approach adopted here works as well as any. Less so with the pagination, which allows the main narrative to be interrupted by an owner’s reminiscence or some other unrelated snippet. Multiple authors tackling different facets of the same story will inevitably repeat each other to some extent, and this too often leads to a disconcerting sense of déja lu. Together with a patchwork of styles—usually taut, but sometimes baggy—the somewhat baffling structure makes it an enjoyably unpredictable read, but firmer editing would have better integrated the various contributions into a more congruent whole (and ironed out the occasionally eccentric punctuation).

As the authors admit, some questions remain unanswered, but history is by nature incomplete. If anything though, the fact that the various gospels aren’t entirely consistent makes the testament all the more convincing. Overall, you get a visceral feel for the enterprise and the people, circumstances and thinking involved. Not the King James’s version perhaps, but a fine and illuminating book.

Copyright 2019, Reg Winstone (speedreaders.info)

This review appears courtesy of the British magazine The Automobile to which Winstone is a contributor.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter