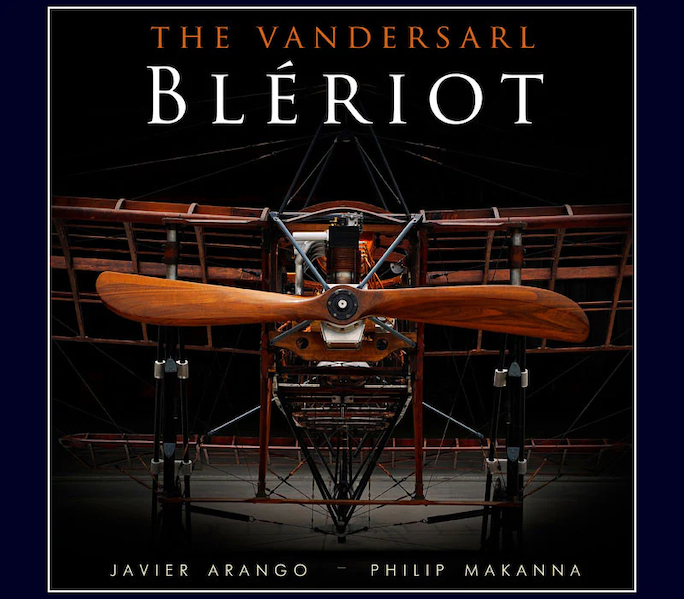

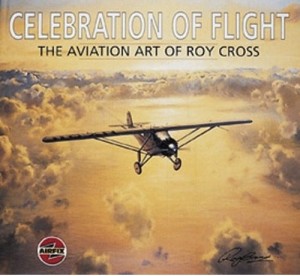

The VanDersarl Blériot: A Centenary Celebration

by Javier Arango & Philip Makanna

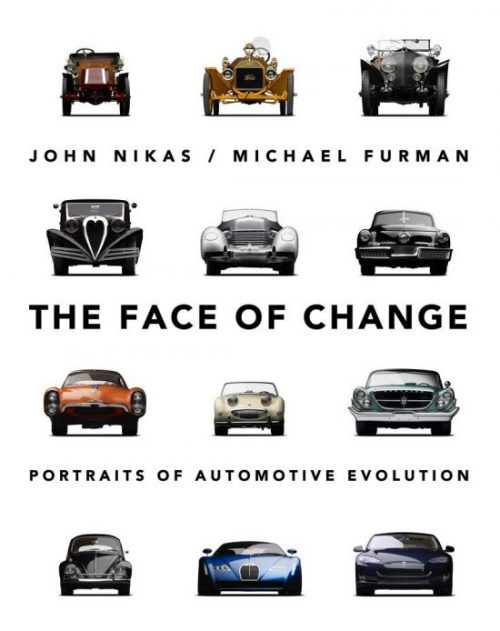

“The lasting memory is not of flight in the modern sense of acceleration, power and performance. It is of how impossibly slow this aeroplane flies, and how absolutely improbable it is that such a machine can actually levitate above the ground.”

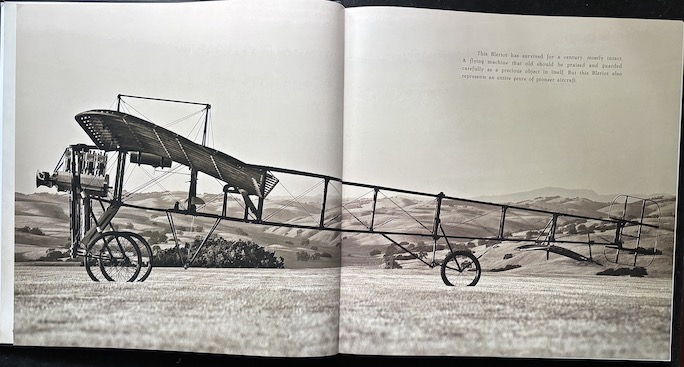

The words above were written a little over a hundred years after this very aircraft’s first flight, in 1911. There are not many vintage aircraft that are still in one piece, let alone flyable.

Blériot is surely a familiar name to our readers: early aviation – French – Louis B. – 1872–1936. VanDersarl, well, that’s rather more insidery.

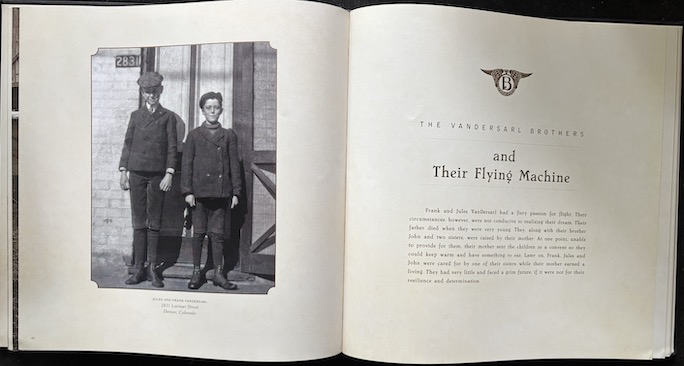

The consensus is that the Wright brothers made the first controlled powered flight. They were in their forties. Two other brothers are paying attention. They are barely teenagers. Their name is VanDersarl, Frank August and Jules Joseph. There’s also John but he plays only an ancillary role. Of course they want to fly. Of course they want to build their own aeroplane. Of course they don’t have the money to buy someone else’s plans and all the required mechanicals. But they have an eye and ear and mind for things mechanical, as one does living on the American frontier where survival depends on being able to make things and keep them in good nick.

Could it be any more rudimentary?

The story that unfolds is worth a book, a play, a movie. What we have here is obviously a book but it is really more of a photo album, which is another way of saying that it doesn’t answer a lot of the questions a story as unusual as this engenders. Moreover, the book is not so much about the lives of the VanDersarl frères (shown below) but that of their flying apparatus. While French in origin, this Blériot is for all practical purposes an American-built machine because the brothers had only drawings and imagination to work with, so it is not a stretch to think of their aircraft as the oldest such on these shores, and not only that, it is certainly the only pioneer aircraft here still flyable. Make that again flyable.

Which brings us to the author of record, Javier Arango, expert on World War I aircraft and the man behind The Aeroplane Collection which repatriated the Blériot to the US and bankrolled its top-notch restoration and re-fabrication. The pen still quivers to have to refer to him as the late Arango: he perished in a crash of his replica Nieuport 28 in 2017, in the prime of life. He was a board member emeritus of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum and so donated several aircraft, including this Blériot, to that institution. We reviewed his posthumously (2023) published book The Nature of World War I Aircraft, Collected Essays elsewhere, and recommend it highly. Both the book and our review also have praise to shower on that other name on the cover, photographer Philip Makanna who is also the publisher of both books, and others as well as most excellent aviation calendars. As always, no book can be large enough to do his fabulous photos justice but even here, at 11.5 x 11.5 inches, you can see not just that he has a good eye and technique but that he is fully attuned to the physicality of flying.

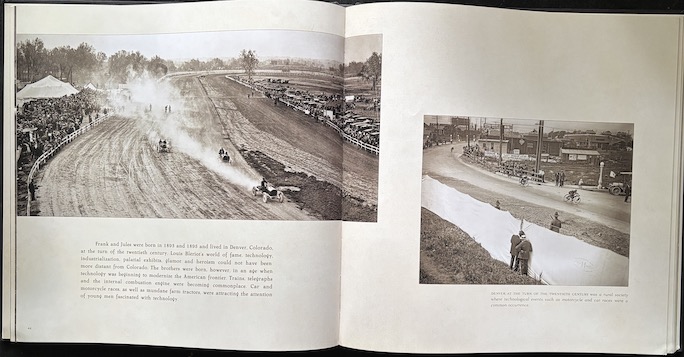

It helps to be reminded what the state of the art was in the world in which the young VanDersarls grew up.

Not being a conventional biography, this book has no Table of Contents. The story is presented more or less chronologically, subdivided into themes. There is also no Index, which, while always desirable in the abstract, is no great practical loss here. Roughly half the book presents archival material into about the 1920s, the other half shows the Blériot after 2008 when Arango bought it and Chuck Wentworth and team at Antique Aero began the two-year process of researching and another two of restoration which includes the scratch-built engine by Rich Galli. There is obviously a large gap in the history between these two principal eras and the book records nothing very useful, especially not about the earlier restoration Frank VanDersarl launched in the 1960s but abandoned (he died in 1983) after which the Blériot changed hands several times, remaining unrestored, unappreciated, but largely original.

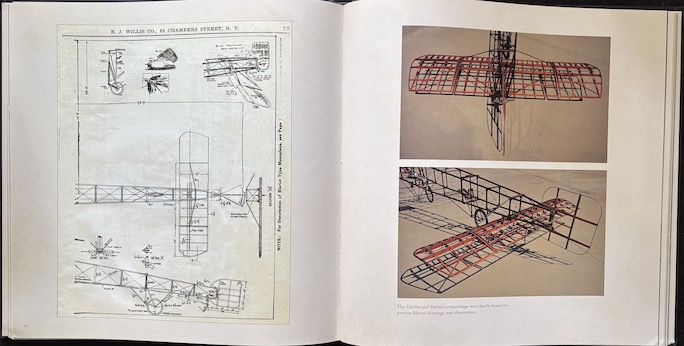

How come the legend on this construction drawing is in English and not French? Because this is not a Blériot blueprint but from a booklet published by an American aeronautical supply house (several pages are reproduced here). What the book doesn’t quite convey is how remarkable it is that the VanDersarls’ version is so dimensionally close. One difference are the frame members that form the space into which the engine slips because theirs is entirely scratch-built, a mammoth accomplishment in itself.

As to the words in the book, nothing is wrong but not everything is clear so don’t go around quoting things without working out context on your own. In other words, an editor would have come in handy. Example: the VanDersarls are described as 10 and 12 years old when the Wrights made their flight. Frank was born in 1895 and Jules in 1893 so that would date the Wright flight to 1905. But they first flew in 1903. What did happen in 1905 was the Wright Flyer III. It achieved much greater performance than I and II, making the longest flight yet and is considered the final iteration. It was disassembled later that year to prevent it from being copied. Another example: Louis Blériot made his famous flight across the English Channel on July 25, 1909 so how did the VanDersarls manage to start building their version not four weeks later when construction plans and details did not appear in US trade magazines until 1910? This lack of clarity should not detract from the book as long as you don’t expect it to be a properly fleshed out history.

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Thank you for putting your shoulder into it. It is SO VERY RARE to see fresh words about stuff that has been around for a bit.

Reviews usually repeat what the last guy said. Not you. You REALLY read it and you REALLY thought about the work. I am very impressed and appreciative. I will forward your review to Javier’s widow and to Chuck Wentworth, the brilliant builder.

Onward ! —Pil