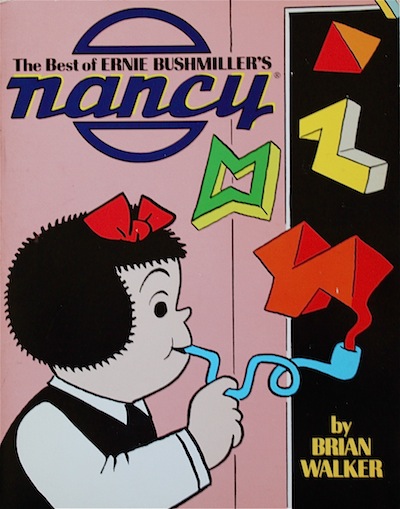

The Best of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy

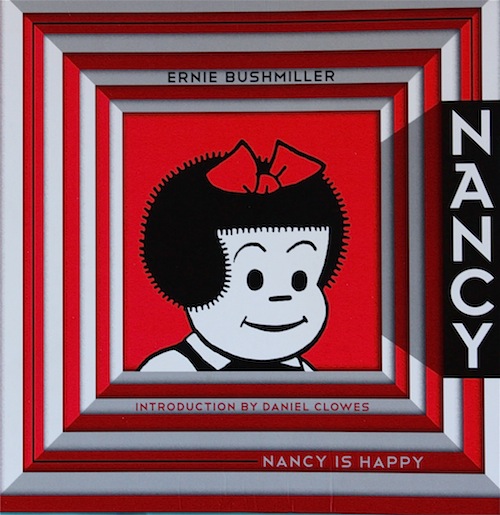

Nancy is Happy

by Ernie Bushmiller

Dailies 1943–1945 (Volume One)

Introduction by Daniel Clowes

Nancy Loves Christmas

by Ernie Bushmiller

Complete Dailies 1946–1948 (Volume Two)

Introduction by Bill Griffith

Ernie Bushmiller (1905–1982) just seems like he would have to be the nicest guy on any block, the smile warm and sincere, and the reports coming down to us, from, among other places, the introductions, prefaces, forewords and afterwords of these books, concur. And anyone who likes Nancy and writes about it tries to figure out who else is liking Nancy and tries to figure out just how many out there also like Nancy, and, finally, tries to figure out just why all of these people out there who really like Nancy—well, like Nancy. The reason for this is that the strip is often so restrained in its humor that many find it bland, unfunny; some say there is no humor to be had. Critics too are wary of the bare-boned, stripped-down artwork, not valuing Nancy’s inherent power of simplicity. The artwork is sly but always designed to enchant the eye as it segues from panel to panel. Included in the Brian Walker book, along with the earliest of Bushmiller’s work, a broad survey of both daily and Sunday strips (arranged thematically), a selection of illustrated essays on Nancy’s impact on fine art, reproductions of these impacted artworks, biographical and archival material and pre-Nancy cartooning, is a convincing deconstruction of a typical Nancy daily. This deconstruction explains the direction of eye travel, breaks down the design of the patches of black ink, stresses the strip’s overall visual coherence, and explores how the drawing, the text, and the gag form a smooth and satisfying gestalt.

Walker’s book, then, although not as visually appealing as the Dailies—it lacks the strong design and æsthetics of their finer paper and superior graphic design—is the better introduction to Bushmiller and comes highly recommended.

And so do the Dailies come with a high recommendation. These are books that would lose a great deal of their magic if read on a Kindle or iPad. The feel, both tactile and visual, of each page could never be fully appreciated on any screen. Each book comes with a very brief introduction and proceeds immediately with the Nancy dailies, printed in the order of publication (a continuation of this series is planned). Most of the pages are designed with three strips, most of which contain four to six panels, mostly four; the three strips are separated by comfortable margins and space in between, and within this in-between space, printed small and very lightly, is the date of each cartoon and the page number.

And so do the Dailies come with a high recommendation. These are books that would lose a great deal of their magic if read on a Kindle or iPad. The feel, both tactile and visual, of each page could never be fully appreciated on any screen. Each book comes with a very brief introduction and proceeds immediately with the Nancy dailies, printed in the order of publication (a continuation of this series is planned). Most of the pages are designed with three strips, most of which contain four to six panels, mostly four; the three strips are separated by comfortable margins and space in between, and within this in-between space, printed small and very lightly, is the date of each cartoon and the page number.

The artwork is presented in a size that mirrors the typical newspaper funny pages (it is actually a bit larger by today’s standards) and the reproductions of the ink drawings capture well Bushmiller’s draughtsmanship, highlighting the crispness of his line and the boldness in his employ of deep black. Occasionally throughout the book, a four-panel strip is given its own page, reproduced larger, arranged with two panels on top, two on the bottom, and this arrangement is not as pleasing. The reason for this has to do with Bushmiller’s refined sense of scale. Although the original artwork would have been drawn larger than the subsequent newspaper publication, Bushmiller, either intellectually or instinctively, realized how the finished product would appear on the page to best advantage. All of this is well and good, but it might be asked why all of this fuss and attention, and the answer has to do with the star of the strip, Miss Nancy Ritz.

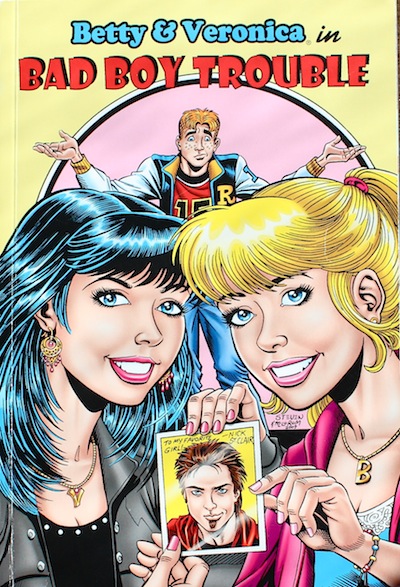

Nancy began her life first in the Bushmiller’s early “flapper” strip, Fritzi Ritz, a niece come to visit, come to stay, and soon Fritzi Ritz was eclipsed, kept on in the Sunday newspapers until 1968, appearing in some venues along with the Nancy strip, but shut down in the daily papers in 1938 in favor of Nancy, Nancy coming into its own. Nancy herself is altogether a wily imp, a sweet child of—what?—seven, a naughty niece, an affectionate niece, naïve in her childhood, sophisticated in an adult world, revengeful, forgiving, sometimes amiable, sometimes sour, but always resourceful, always with an underlying harboring of kindness and generosity. It really isn’t that great a stretch to say that she is multi-dimensional, a gently rounded fictional character. She has been around since 1933 and she is still around: Guy Gilchrist’s current strip, available online as I write, is a more than fair homage to the original Bushmiller sensibilities. It’s Nancy’s toughness and adorability; her devotion, as both a girlfriend and best friend, to Sluggo Smith; her believable “mother-daughter” relationship with her Aunt Fritzi, never sugarcoated but always loving; and her credible interactions with her friends and community that have kept the admiration alive through all of these years—not to mention the playfulness and ineluctable charm of the strip.

There are several ways to approach Nancy, from Andy Warhol’s nod of approval—Nancy was one of the relatively few cartoon characters that he painted or silkscreened on canvas—to Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik’s “How to Read Nancy,” from Bill Griffith’s tribute to Nancy by way of Zippy the Pinhead to a growing body of academic consideration and study. I would here attempt yet another approach to look at Bushmiller, one not entirely original as the influence of modern art upon his work has been noted by others, but I would like to take another, more specific, step in this direction. I want to focus on the influence that the painter René Magritte (1989–1967—another nice guy by all accounts), either consciously, unconsciously, or serendipitously exerted on Bushmiller’s art. My reason for so doing is that the panels that show this influence are so compelling, so inventive and reasonably numerous, that a consideration of them, in the interest of both scholarship and delight, is in order.

There are many books available on this fascinating Belgian painter. Amazon, for example, offers over 60 pages of them from which to choose. There are essential Magrittes, portable Magrittes, catalogues raisonné of Magritte, biographies of Magritte, studies of Magritte, a Magritte A-to-Z, Magritte calendars and even Magritte—functioning—umbrellas. And although I admit freely to neither having begun to have read all of these books nor to using the calendar or the umbrella, I do admit to a familiarity with his art. Magritte maintained that he was not a painter but rather a philosopher who used the canvas to set forth and elucidate his ideas. He postulated an underlying affinity between the most disparate objects; he, like Ludwig Wittgenstein, puzzled over the wooly relationship between words and the world; he questioned the essence of reality and our awareness of it; and he asserted that points of view are neither static nor reliable. It is in these last two that a kinship between his work and Bushmiller’s can be drawn. For the sake of brevity, let me offer but three corresponding examples.

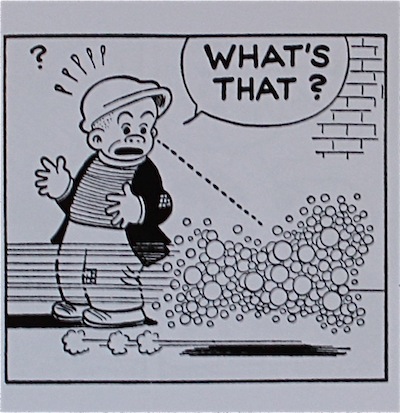

In 1930 Magritte painted L’evidence eternelle (The Eternally Obvious): five panels, framed and mounted one atop the other, showing respectively the partial face, the breasts, the belly and pubic area, the thighs and knees, and the lower calves and feet, of a nude woman. Nancy, in 1948, concerned that she is putting on weight, stands before a series of four mirrors, one each for her head, left hand, right hand and two feet, eliminating the problematic middle. In a 1946 cartoon, Nancy’s dog

In 1930 Magritte painted L’evidence eternelle (The Eternally Obvious): five panels, framed and mounted one atop the other, showing respectively the partial face, the breasts, the belly and pubic area, the thighs and knees, and the lower calves and feet, of a nude woman. Nancy, in 1948, concerned that she is putting on weight, stands before a series of four mirrors, one each for her head, left hand, right hand and two feet, eliminating the problematic middle. In a 1946 cartoon, Nancy’s dog  is seen only as a froth of soap bubbles in the shape of a dog; these panels parallel, among other paintings, Magritte’s 1953 Le seductéur (The Tempter), where the ocean water extends upwards forming an outline of a sailing ship. Magritte’s Les vacances de Hegel (Hegel’s Holiday), 1953, shows an open umbrella supporting a nearly full water glass on its top, and this image seems to be supporting the same confluence of thought as the 1945 panel showing Nancy using a cooking pot to catch the water from her leaky umbrella. There are other examples—to start, check out Nancy April Fools daily strips throughout the years. I am not arguing here a one-to-one cross-pollination between the two artists. Each one, Magritte and Bushmiller (Ernie and René would have liked each other’s company), obviously had his own agenda and each had, too, a larger body of work that obviously diverges one from the other; but an undeniable affinity for the metaphysical and of wry humor, a seriousness of the silly, ties them together, as if during the 1940s through the 1960s something new, benign, nebulous and delectable was in the air.

is seen only as a froth of soap bubbles in the shape of a dog; these panels parallel, among other paintings, Magritte’s 1953 Le seductéur (The Tempter), where the ocean water extends upwards forming an outline of a sailing ship. Magritte’s Les vacances de Hegel (Hegel’s Holiday), 1953, shows an open umbrella supporting a nearly full water glass on its top, and this image seems to be supporting the same confluence of thought as the 1945 panel showing Nancy using a cooking pot to catch the water from her leaky umbrella. There are other examples—to start, check out Nancy April Fools daily strips throughout the years. I am not arguing here a one-to-one cross-pollination between the two artists. Each one, Magritte and Bushmiller (Ernie and René would have liked each other’s company), obviously had his own agenda and each had, too, a larger body of work that obviously diverges one from the other; but an undeniable affinity for the metaphysical and of wry humor, a seriousness of the silly, ties them together, as if during the 1940s through the 1960s something new, benign, nebulous and delectable was in the air.

Read Bushmiller’s Nancy every day. It’s good for you.

Copyright 2014, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

The Best of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy

Henry Holt / Comicana, 1st edition 1988

236 pages, softcover

List Price: $10.95

ISBN-13: 978-0805009255

Nancy is Happy

Series: Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy

Fantagraphics, Reprint 2012

336 pages, softcover

List Price: $24.99

ISBN-13: 978-1606993606

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter