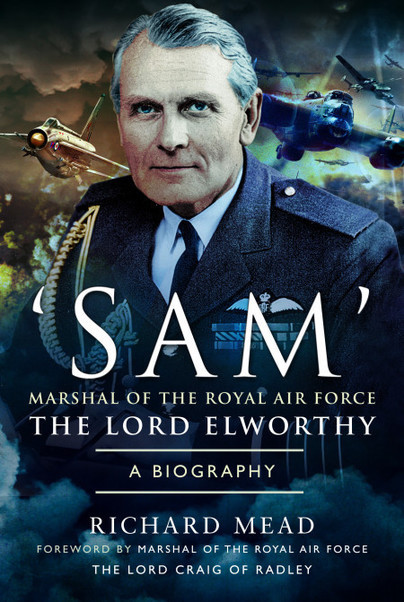

“Sam” – Marshal of the Royal Air Force the Lord Elworthy

A Biography

It has been a pleasure even to open this book, printed on excellent paper and well hard-bound in Britain, presented as it is with a readable and clear font. Since I had just ground my way through the 600 fragile pages, of minuscule font size, of Nicholas Shakespeare’s biography of Bruce Chatwin (Vintage, 1960), this is an emotional relief.

Richard Mead’s book does, however, share the biographer’s dilemma with Nicholas Shakespeare, and with Tom Scott and his biography, Searching For Charlie (Upstart, 2020) which I reviewed for this site; how does one address the subject of a biography? The late Miles Kington used to write a delightful column in The Independent, reminiscent of New Zealand’s late hero Alan Grant’s writing in The Listener. Kington answered the question, perhaps his own, “How do close friends address The Dalai Lama?” with, “They call him by his first name, of course; ‘The.’” While “Bruce” sounds a bit matey, “Charlie” seems far too familiar for Captain Charles Upham, VC and Bar, and Mead has settled for cutting through Lord Elworthy’s titles and honors to a mere “Sam.” Mead tells us that new acquaintances, wondering about how correctly to address Lord Elworthy, were told, “Just call me Sam.” Hmmm.

That out of the way, now to the book.

Richard Mead has written several military histories and biographies for this publisher, Pen & Sword, and in this case actually met his subject. They had in common an education at Marlborough College in Wiltshire, and playing trombone in the school cadet corps, which led to one of the school’s most eminent ex-pupils levelling his piercing gaze upon his future biographer.

Mead is very good at providing context; the names that inhabit the book, and their connections, will have you busily consulting Mr. Google as you read. And a good map of Britain; the author is English, and writes from that vantage point. In some ways this is appropriate, as Samuel Elworthy’s father, although New Zealand-born (in 1881) had no interest in taking up his farming inheritance, and after what seems to have been an unhappy time at school in Christchurch, ensured that his sons were educated in the rigor of British “public” schools after an initial education with a tutor at the farm in South Canterbury. From 1924 the family often lived in England for long periods, and Sam Elworthy visited his home country only in 1932 and 1946, before making a point of retaining his links during the latter part of his Royal Air Force career.

That career was not his first choice, as he studied law at Trinity College, Cambridge, was actually called to the bar, and as well had some experience at stock-brokering. His brother Tony had learned to fly, but Sam Elworthy’s activities as part of the Trinity First Rowing Eight clashed with the Cambridge University Air Squadron. He joined the Reserve of Air Force Officers, and attended the flying school run by de Havilland at Hatfield, passing out with an “exceptional” rating. Then came service with the Royal Auxiliary Air Force, and at the relatively advanced age of almost 25 he was commissioned as a pilot officer, one of the few to enter the RAF after university, rather than coming through Cranwell. From being perhaps the oldest pilot officer in 1936, in September 1962 he became the youngest air chief marshal.

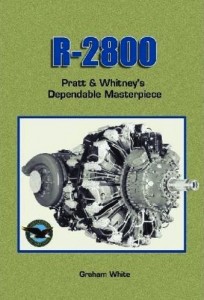

After early training on the inevitable Moths and then the well regarded Hawker Harts, Elworthy was posted to XV (Bomber) Squadron at Abingdon in Berkshire in late 1935, using the Harts as dive-bombers. His legal training came to light, and he was soon appointed Squadron Adjutant. Then came the conversion to the twin-engined Bristol Blenheim, and he was soon involved in training the inexperienced new arrivals from the Royal Air Force Reserve during those stressful few months leading up to the declaration of war. The heavy radial engines made the Blenheim behave utterly differently from the Tiger Moth, so the received wisdom of gaining height to militate against engine failure led to many training accidents. The Central Flying School was unable to provide training methods to cope with the flying characteristics of a wildly diverse range of aircraft, and Elworthy had success with innovations in night flying training, eventually adopted by CFS. This indirectly led to contact with Air Commodore the Honourable Ralph Cochrane who had been instrumental in the formation of the RNZAF. More consultation of reference sources will provide happy hours’ reading of Cochrane’s ancestor, the prototype for many Royal Navy legends.

The Blenheim was outclassed, and suffered a high casualty rate during the difficult bombing raids on heavily defended targets. Elworthy earned a DSO and DFC during his 35 missions, but he was appointed as Wing Commander to an organizational task with Bomber Command under Air Marshal Arthur Harris. His communication skills and his ability to get along with all ranks were major contributions to the wartime effort, and his postwar rise to the top of the Royal Air Force was inexorable and reported in detail.

By 1950 he was a Group Captain, and at short notice made the arrangements for the royal visit to the Farnborough Air Show. Probably as a result, early in 1953 Air Chief Marshal The Earl of Bandon (out come the reference resources again) asked to see him, and Elworthy became the organizer for the RAF Coronation Review. This major event rivaled the now legendary Spithead Naval Review, and was a complete success, no doubt ensuring his attendances at the RAF Staff College and Imperial Defence College, and his rise to the top of the service.

The personal costs of the stresses of high office are noted, with intestinal ulcers sidelining him at the time of the Suez Crisis in 1956, and heavy smoking of both Sam Elworthy and his wife Audrey is mentioned. She was born in Australia but brought up in New Zealand, and they married in 1936, seeming to have enjoyed an active social and sporting life; the personal notebooks of Lady Elworthy, herself an Honours Graduate, must have greatly helped the biographer. It should also be noted that she worked during the war on electrical components and repairing aeroplanes. Her premature decline is very sad, and is probably the main reason for the couple’s retirement to the family land near Timaru, instead of the accolades and sinecures on offer in Britain.

It was an amazing life, and at his memorial service at St Clement Danes Sir Paul Wright said, “I can think of no one of similar stature who went through life without, so far as I know, making a single enemy.” Mead confesses that, because his subject was so universally liked and admired, it would be difficult to avoid the accusation of delivering a hagiography.

He provides a great deal of detail about the large cast of characters who inhabit the pages, and of the aircraft. He spells ”Gipsy” the de Havilland way, but unfortunately gives that firm a capital “D.” A good index, bibliography, notes and footnotes, 30 pages of black-and-white illustrations, and glossary of abbreviations are provided.

Richard Mead has written an important account of an eminent man.

Copyright 2020 Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter