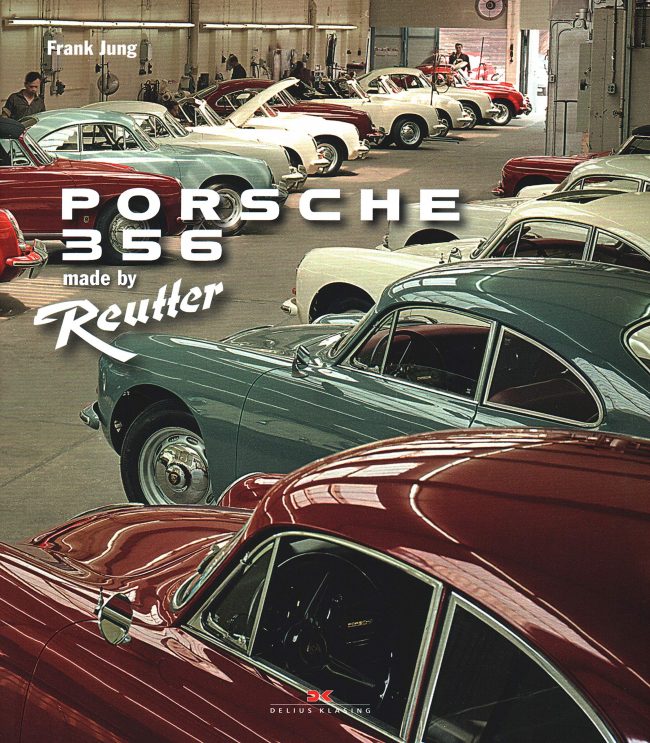

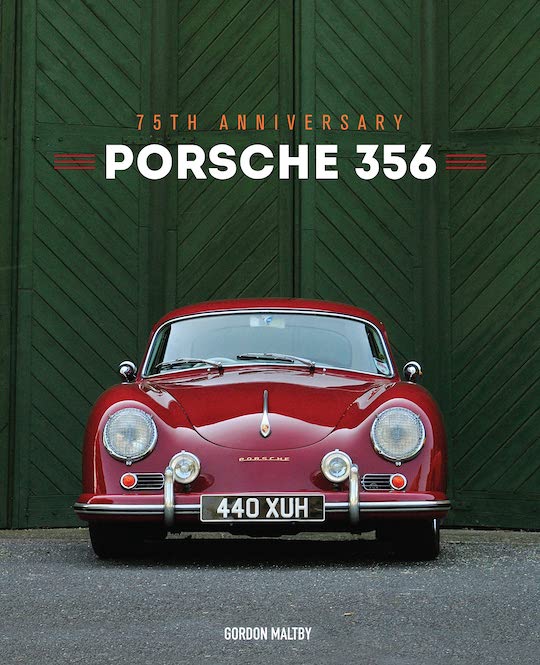

Porsche 356: Made by Reutter

by Frank Jung

“Reutter was constantly searching for ways to improve production processes and to remedy shortcomings in the still nascent series production. The body shop could handle constructive criticism. However, the management did not consider it acceptable that Porsche ‘threatens us at every opportunity to want to use another bodywork factory’ and clearly took issue with this kind of approach. After all, Reuter had been able, with unflagging effort, to build a vehicle that could compete with other mass-produced—under more favorable conditions—vehicles. ‘We would be be pleased if, in addition to some legitimate complaints, you could also acknowledge this side of our joint work so far.’”

Since the relationship between the two firms continued for another dozen years and more after this 1951 memo, such growing pains obviously worked themselves out, blossoming in fact into what the author describes as by and large a “sympathetic marriage of convenience.”

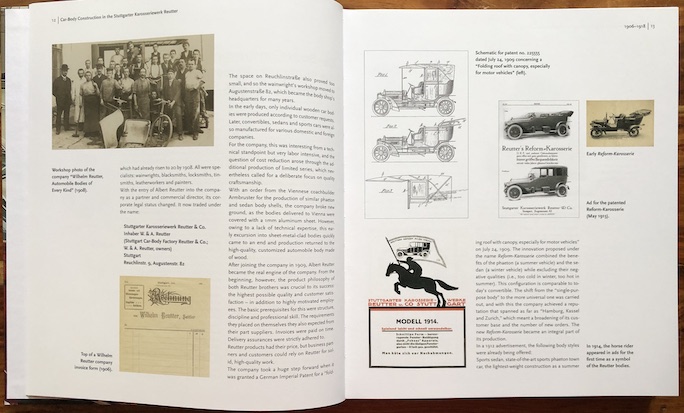

But let’s pick up a different thread first. Six degrees of separation: the author of this Reutter book also wrote one about Recaro. Why is this of interest? Recaro once was Reutter, and to Jung these aren’t just any old companies but family ties: he is the great-grandson of Albert Reutter, younger brother of Wilhelm who founded the firm in 1906. Meaning? Jung has the inside track to get into the family archive and unlock other resources such as that tight-knit group of former employees who contribute their oral histories here. How much the Reutter folks consider each other family is well expressed in the nickname Jung’s forebear, Albert, who had joined in 1908 as a partner, came to be referred to after he had assumed overall leadership in 1918 upon Wilhelm’s retirement: Father Reutter.

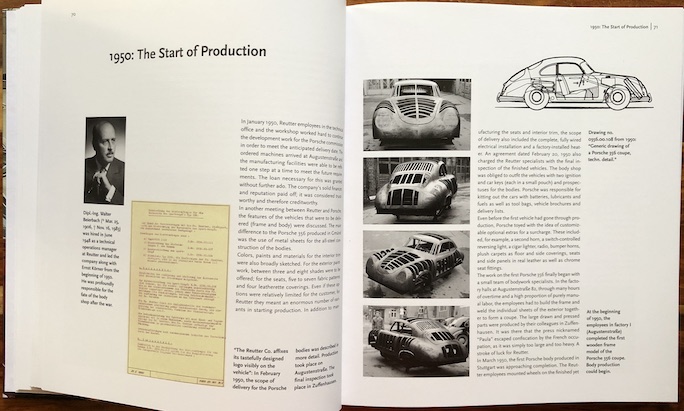

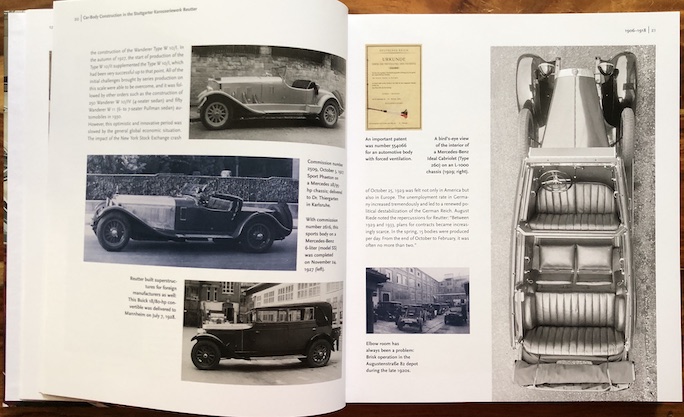

Foreword-writer Dieter Landenberger, whose business card these days says Heritage Director/Volkswagen Communications (this may take some getting used to for long-time Porsche readers who know him as the keeper of the keys to the Porsche Archive), calls Jung “a passionately committed author” and the book’s depth “impressive” and deserving of a special place in the Porsche literature. And he would know, not least because the Porsche Archive contributed items from their holdings of the almost completely preserved Reutter/Porsche business correspondence, something that has not ever been seen in print before. A much more granular picture thus emerges, which, as Jung writes early on “will, with any luck, thrill more than just Porsche enthusiasts.” Indeed it should, not least because the first two chapters, some 60 pages, offer a sweeping overview of German car manufacture/rs starting in 1906 with Reutter’s founding and go up to 1949 when the end of WW II ushered in an era of new opportunities. The Reutter/Porsche connection had begun many, many years before that, when Ferdinand Porsche first hung a shingle on his door after his stint as technical director at Mercedes Benz and started doing contract work for a number of makers, of whom some were already working with Reutter. Porsches of Type 7, 8, 12, 32 and 60 (the Peoples’ Car) are discussed, and by this point in the book the Porsche 356 is the obvious, clear, natural next step.

Thanks to the Porsche Archive there are many facsimiles of correspondence and other realia but they are reproduced almost too small to read.

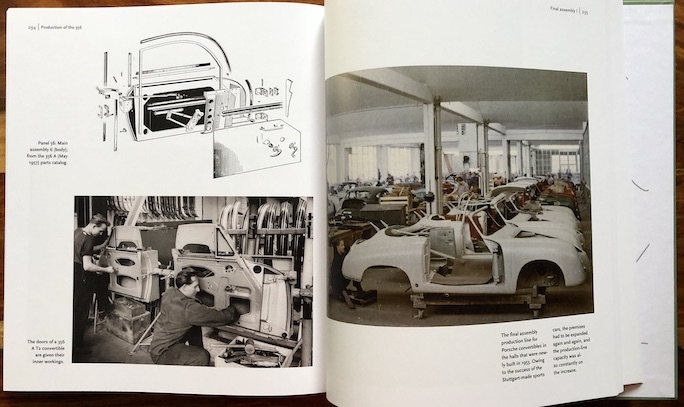

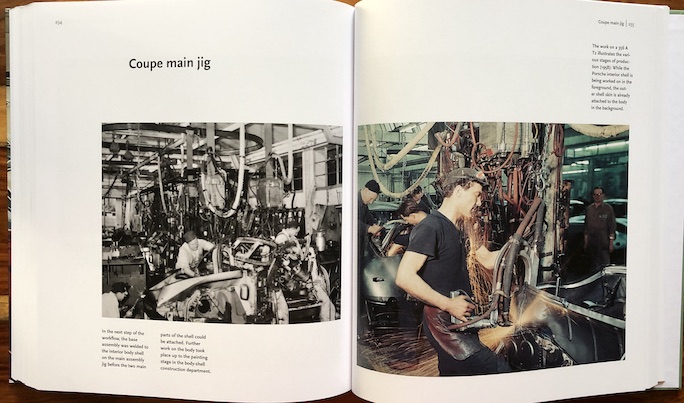

The different models/variants are described in year order, 1949–64 (the year Recaro enters the picture). This is followed by a short photographic tour of the Training Workshop, and then a penultimate chapter of a 100-page-long look at processes on the shop floor including kitchen and canteen. Here the aforementioned oral histories really move the needle because they shed light on real-life practices not recorded elsewhere or prescribed in any official manuals.

Appended are several pages of Reutter/Porsche advertising and a quite detailed List of Sources. As is typical for this publisher, there is no Index.

An aberration in the Introduction deserves a few words. In explaining how the book will unspool its exposition it previews the contents of the subsequent chapters by referring to them by number—but the Table of Contents lists only chapter heads not numbers. As there are only six you can’t get too far off course.

The book was first published in 2011, but only in German, to the frustration of all who wanted more than just look at the illustrations, of which there are many although some quite small. This 2019 reprint has expanded text and additional photos, and the English edition sports a really delightful translation that in a way reads much “easier” than the German original, a function of syntax and cadence rather than the translator taking liberties with the native text.

Copyright 2021, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter