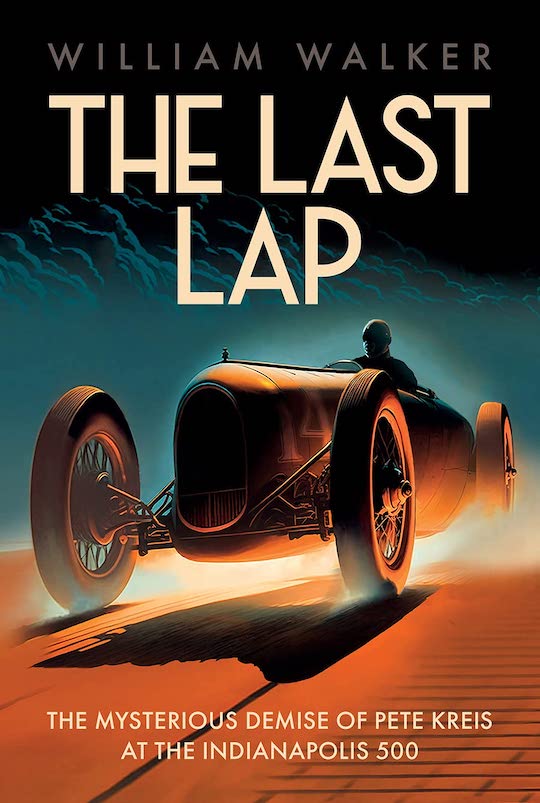

The Last Lap, The Mysterious Demise of Pete Kreis at the Indianapolis 500

by William T. Walker Jr.

by William T. Walker Jr.

“At the time, there was quite a lot of discussion in Gasoline Alley about the accident. There were no mechanical failures in the car, no track incidents that caused Kreis to swerve, and no tire marks indicating that he fought to avoid the deadly event. There was speculation that Pete may have fainted, although he had passed a track physical a few days earlier.

The next year, an unofficial ‘coroner’s jury’ of Indy drivers and Speedway officials held another intense review of the accident. After mulling over the evidence, they concluded Pete’s demise was ‘the strangest death in all racing history.’ They went on to imply that the accident may have been suicide.”

That was 1935, and we still don’t know today what really happened, mainly because no one but the author is looking for answers. He’s been looking for a good sixty years. Why? Because Albert Jacob (Pete) Kreis was his cousin, albeit from a distant side of the family that was not much talked about, for reasons this book examines.

If we were just any old fools, the review would end here. Many have, and have missed the point.

Walker considers it a hard book to write, harder still because, following the Holmesian dictum “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth,” he finds himself in the suicide camp. But with a twist: the loss of the ability (will?) to self-preserve and withhold oneself from mortal danger due to, as Sigmund Freud had once described it after treating scores of World War One soldiers, a compulsion to seek out self-destruction as a means to find release from the enduring pain and tormenting memories of a past trauma. And Kreis had had such a trauma. And his head-strong father—motto: what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger—had pushed him back into it. The story is no longer one of adrenaline-junkie recklessness or hubris but a cry not so much for help (in the form of a process of healing) but to lay down “the burden of memories” once and for all. And there is a twist to the twist: all of the foregoing = check, plus a momentary recurring “blanking out” brought on by sudden, unpredictable flashbacks to the road accident in 1924 that killed the young neighbor who rode with him.

On top of that, Kreis had career and family pressures weighing on him, and his two brothers “died in self-destructive ways, propelled by their father’s aspirations.” And what to make of this: before his last lap he handed a treasured diamond ring to his crew chief with instructions to deliver it to his sister—”if anything happens to me“—who had long tried to sweet-talk him into giving it to her . . . the plot thickens. His sister called it premonition, Walker calls it . . . well, now we’re getting a bit into the weeds.

That Walker has a point of view is a given. If you are of a lawyerly disposition you will find his arguments sometimes falling short of definitive inevitability while they drive the story towards a specific outcome. He does give credit to an editor but it is not clear if that person just sprinkled a few commas around or puzzled out the book the way a reader without preconceived notions would. Consider: suicide by car seems a terribly imprecise way of ending it all, never mind the potential for unforeseeable collateral damage. (Tempers will flare to see Alberto Ascari and Niki Lauda [not the Nürburgring fire but considering suicide by car to escape debts] roped into this chain of thought.) Further, if Kreis was set on killing himself, he practically murdered his riding mechanic. Spoiler alert: this aspect of the story is given barely a page of consideration, and basically dismissed as unavoidable. (Remember that Kreis crashed on a practice lap; the race proper required a riding mechanic aboard so he did need to set up the car during practice with that extra weight factored in, but could Kreis not have done a last lap without him?)

Remember the “twist to the twist” talked about before? The only way Walker can make the homicide issue go away is by removing intent on Kreis’ part. In other words, yes, Kreis had suicidal ideation, meaning he ruminated about suicide in the general course of life, but on that last lap, in that exact moment he did not mean to kill himself, and thereby his mechanic, but was overcome by a fog, a waking dream, frozen in paralysis, unable to maintain situational awareness, and went off the road.

On p. 241 of 264 Walker is ready to declare that his final analysis. And out of the blue, cousin Hazel (Pete’s sister to whom the aforementioned jewel was left), nearing the end of her life, is overcome with the urge to add to her recollections she had shared a decade earlier. She tells him that story of the diamond ring, a story that only three people know. It changes everything. For Walker it is the smoking gun. It manifests one of the three indicators psychologists would look for in diagnosing suicidal intent: Kreis was set on ending it then and there. Whiplash. This way of stringing the story together only works if the reader stays with it, reads every word on every page, and remembers what came before.

Don’t let any of the foregoing dissuade you from reading the book and thinking about it deeply. Even if you were to dismiss it as merely a yarn, the book is engagingly written, covers a lot of ground in regards to early motorsports in America (Kreis raced at Monza too but that is merely a side show here. By the way, Indy driver Rex Mays is another cousin of Walker’s.) and, not least, wrestles with some very big question in regard to free will, determinism, fate, and also family dynamics, not to mention mental health.

Note, too, that Walker started his professional career teaching composition and literature at university level—he loves good writing, and the narrative nonfiction genre is his forte. And while he spent the majority of his career in academia on the admin side, he is no stranger to scholarly rigor. To wit, there are endnotes, a bibliography, and an index. The notes, though, have limited utility inasmuch as they mostly list the source material from which verbatim quotes were pulled rather than substantiate factual statements in the text or offer elaborations upon it. Readers deeply immersed in motorsports history will absolutely find things to quibble about, but nothing truly major. Example: Frank Lockhart occurs several times in the text but the comments regarding the circumstances of him acquiring Kreis’ Miller do not reflect conclusions laid out in what is surely the definitive Lockhart bio by Morgan-Wu/O’Keefe (2012) which is also not listed in the bibliography. Walker’s telling does not alter the broad sweep of history but shifts the psychological dynamics of that moment and what the principals took from it (which, in a book that pivots on the impact of subconcious stirrings, is absolutely relevant).

Already in the 1970s when he first made contact with his cousin Hazel, Walker told her he had a book in mind, and she wholeheartedly endorsed the endeavor and supplied primary sources. He is coming up on eighty. He could have finished the book anytime, so why now? In the Acknowledgments he singles out his doctors, for a procedure that is right up there in get-your-house-in-order territory. Yet as late as May 2022, Autoweek senior correspondent (and fellow Octane author) Al Pearce, who is expressly acknowledged as “especially helpful,” wrote in that magazine “Even with no assurance his meticulously detailed and well-balanced manuscript will ever be published, [Walker] continues to research the family tragedy.” Twelve months later, the book is in the stores, right in time for the 2023 Indy 500. That is clever timing . . . it beggars belief to think the publisher could have also known that another relevant event would transpire a few weeks later, and for this one year only not on its home turf the Milwaukee Mile but in Indianapolis. Well, Lucas Oil Indianapolis Raceway Park which is just a few miles away. That event is the Harry A. Miller Club meet, and Millers play a key role in the Kreis story. Walker intends to be there so pencil July 6 & 7 into your calendars.

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter