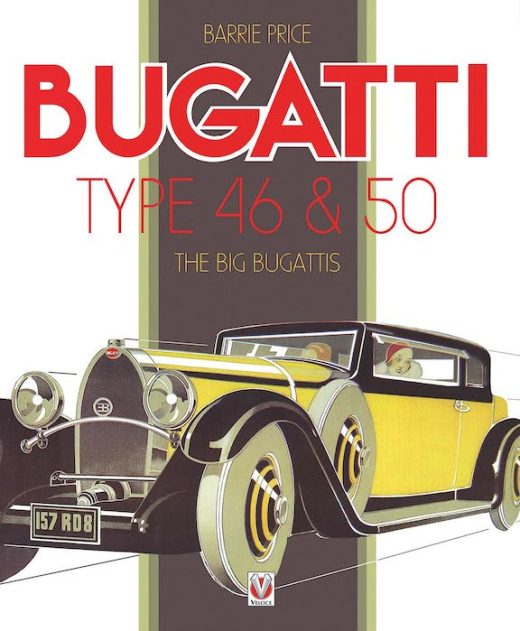

Bugatti Type 46 & 50: The Big Bugattis

by Barrie Price

by Barrie Price

“Ettore Bugatti had in mind, from the early days prior to 1914, that he would one day build the ultimate large luxury car. This intention clearly indicates that Bugatti was convinced, even as a young man, that he was capable of anything in the field of engineering. Subsequent events proved this notion nearly correct.”

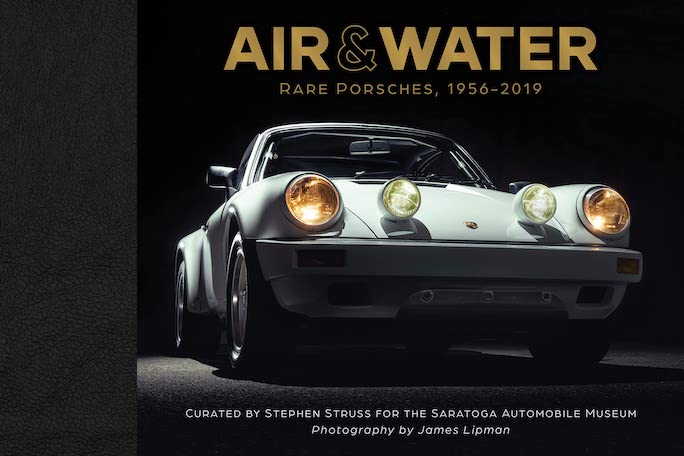

A primary reason to dig up a book first published in 1995 and then revised for 2010 and reprinted in that form in 2015 in this publishers “Classic Reprints” series is that big Bugattis are not merely a thing of the past. As recent as 2009 there was the 16C Galibier 5-door fastback concept car—the name referenced the Type 57 Galibier four-door sedan of the 1930s—on the drawing board, with a planned production date of 2014/15. Now that Rimac Automobili (in which Porsche has a 24% stake) owns the brand that Volkswagen Group had saved from oblivion in the 1990s, there is again talk of a big Bugatti.

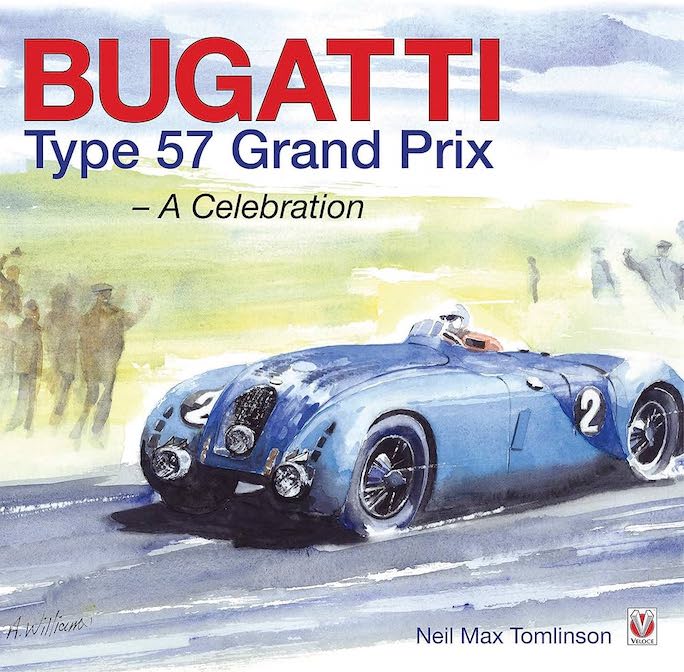

No less mind-blowing in its day than a Veyron is today.

VW Group had in fact produced four Bugatti prototypes and it was easy to see that the new and the prewar cars had more in common than just their nameplate. Obviously not in terms of technical specs but by way of “styling references” such as the horseshoe grilles, aluminum wheels with flat centerpieces, turbine-blade spokes, etc. More importantly, there were similarities in “spirit”—how they address their market segments and how they separate themselves from the competition. The 4-door 218, for instance, is similar in intention to the old Type 46, the subject of this book. The two 118 prototypes evoked the old T57C Atalante and 57SC Atlantic, the subject of Price’s next book.

And author Barrie Price is another reason to welcome any of his books into your library if you haven’t already; this particular book has remained the only one on this topic. As chairman of the Bugatti Trust he has been involved with “Bugs” all his life. This revised and enlarged version of the original 1995 edition is an illustrated history of the Type 46 (1929–36) and its successor, the T50 (1930–34). The introductory text is a bit sparse and establishes only the briefest of contexts. No mention, for instance, that the ultra-expensive T50 in particular was very much intended to be a “Bentley beater,” at least domestically. Their reputation for difficult handling prompted the British importer, Colonel Sorel, to refuse selling them and of the 65 made only one found its way to a British customer (chassis 50118, Sir Robert Bird).

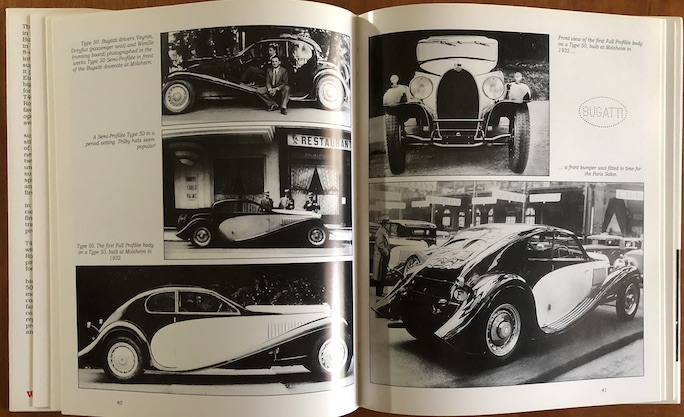

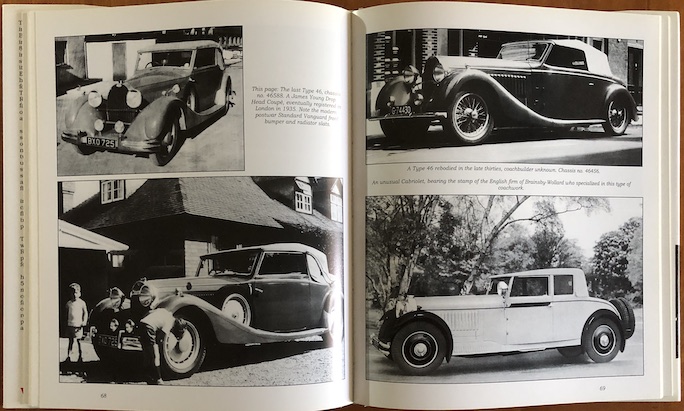

A bit more pedestrian than the Profilée above but all the cars on this spread have unusual coachwork features.

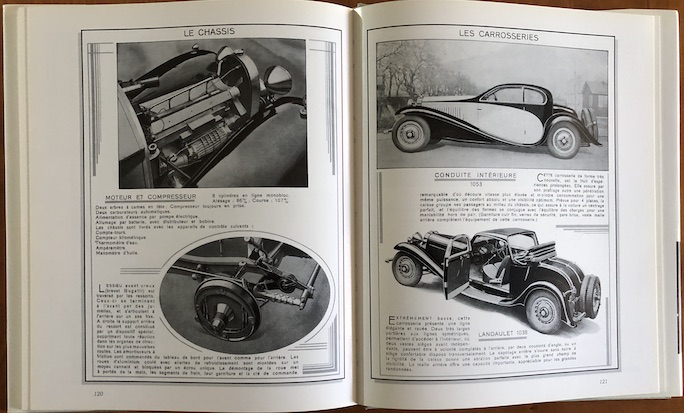

The remaining text is concentrated on extensive photo captions, many of which call out specific features. The photos are divided by body style and, given their age, of mostly good quality. Coachwork aficionados will find much to marvel at, even if the b/w images can’t do justice to the stunning bodies. Of particular relevance to the technically minded enthusiast is the appropriately named “Anatomy” section that contains interesting close-ups of engines and assemblies. These models were the first with twin-cam engines, the first straight-8s, and sport a number of innovative solutions to the very same problems the firm’s competitors were struggling with.

From an original (undated) Bugatti brochure.

Appendices contain complete chassis listings, all standard and coachbuilt bodies, period sales and promotional material, and factory sales records.

If all you know about Bugs is Ettore’s snub (apocryphal at that!) about Bentleys being the “fastest lorries,” this book will go a long way towards illustrating the differences between the marques.

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter