Charlie Schwab, President of Carnegie Steel, U.S. Steel and Bethlehem Steel

by William R. Huber

by William R. Huber

The subtitle could have read “an overview of the early history of the US steel industry” for that is the overarching story on the pages with a common thread running through it. That thread is Charlie Schwab.

His involvement in the industry began in 1879 when he was all of seventeen and hired to be part of a team dragging chains, setting plumb lines and the like at Andrew Carnegie’s (1835–1919) Edgar Thomson Steel Works and Blast-Furnaces in Braddock, Pennsylvania. Before he was done, Charles Michael Schwab would, as this book’s subtitle does say, become President of Carnegie Steel, U.S. Steel and Bethlehem Steel.

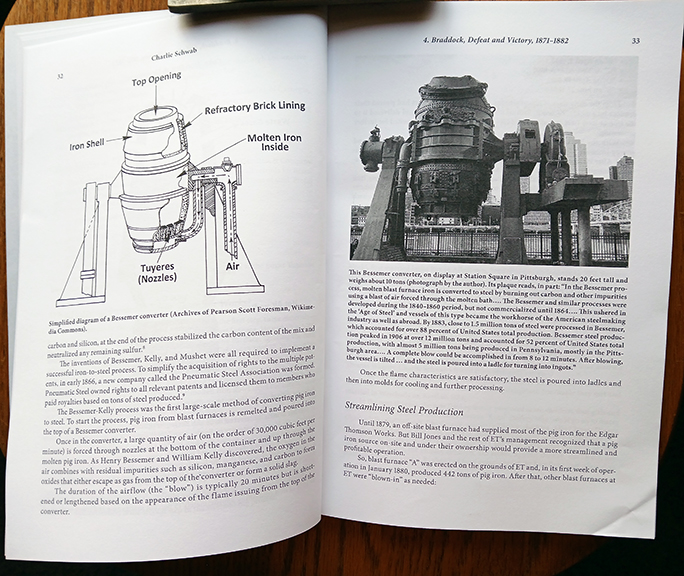

Key to converting raw pig iron (so called because the sand-filled trenches used to contain the molten iron resembled a sow feeding her piglets) into a strong steel was the Bessemer converter shown in diagram and photo.

This book’s author cites two earlier titles as major sources. Sadly neither has your commentator read and even more sadly my local library has neither on its shelves. That is becoming more and more a reality as local libraries are focusing on things digital thus reducing their costs maintaining actual books on shelves. (Sigh!) That said, surely print copies of Robert Hessen’s Steel Titan, published 1975, and Kenneth Warren’s Industrial Genius: The Working Life of Charles Michael Schwab, published 2007, ought to be available via the library interchange. But that won’t happen prior to sharing these thoughts and assessments on this book with you here and now.

This is Huber’s third biography of someone previously rather overlooked by biographers: specifically George Westinghouse and Adolph Sutro also reviewed for you here. Part of William (Bill) Huber’s motivation to explore and write about Schwab included a shared-in-common background albeit decades apart. Both men are Pennsylvanians by birth. As Huber’s Preface details, their existences were intertwined as Huber’s dad had been employed by Schwab during the time Schwab had headed U.S. Steel.

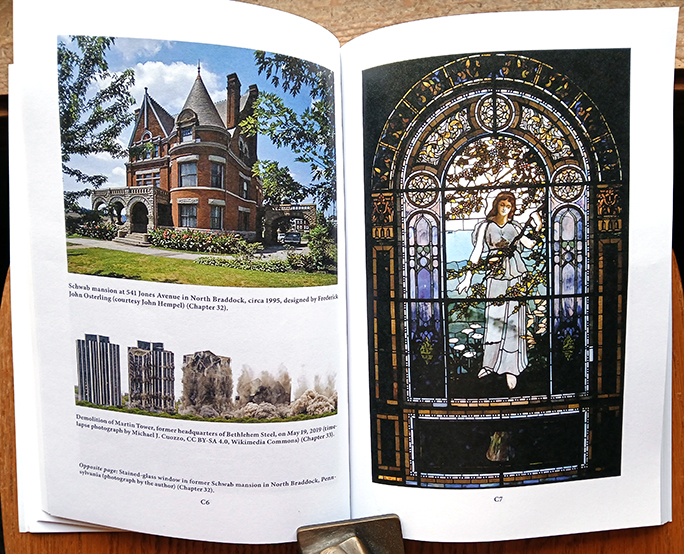

Top left, the Schwab mansion, today called Schwixon, treasured, lived in and gradually being restored back to its original glory. Beneath are time-lapse images of the demolition of one-time Bethlehem Steel headquarters in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Facing page is an original stained glass window still in Schwixon.

Although Huber no longer lives in Pennsylvania, he has retained close ties with many in the area. His inquiry into Schwab’s life and existence netted some rich resources including two who today live in homes previously occupied by Schwab. One is a directly related a first cousin twice removed who “spent his life collecting and cataloguing material about Charlie, his accomplishments, and his activities.” The other contributed this book’s Foreword as he occupies and is restoring the mansion Schwab and his wife Eurana lived in during those early 1890s while Schwab was employed as superintendent of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works.

Huber made an additional and particularly rich discovery as research progressed. Back in the day a journalist named Sidney Whipple had secured Schwab’s permission to “shadow” him daily and for hours on end. The goal was to one day produce Schwab’s authorized biography. But Schwab’s permission was conditional. Whipple couldn’t publish until after Schwab’s death. It was an agreement that Whipple breeched and Charlie immediately responded causing many of Whipple’s notes to be destroyed. Those documents that managed to survive are today housed in the archives of Delaware’s Hagley Museum and Library which is where Huber found and accessed them. Rich stuff indeed. It is those heretofore undiscovered, thus previously unplumbed, resources containing information that enriches this most recent biography.

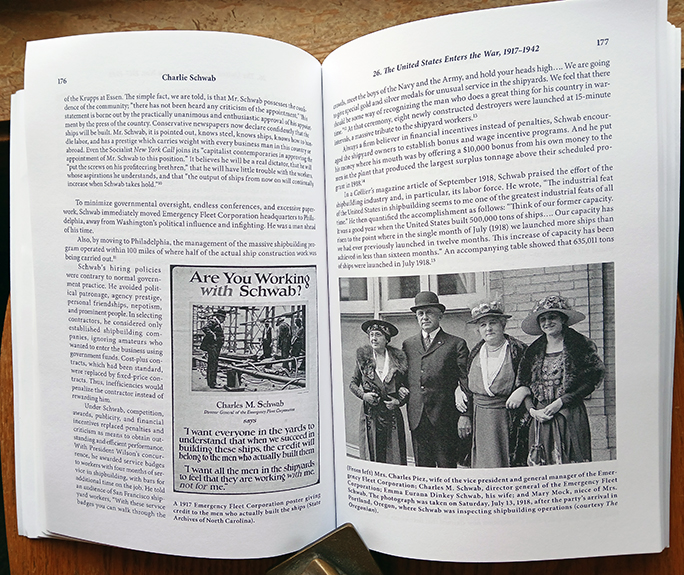

Poster on left page very much expresses Charlie Schwab’s feelings. The last line reads, “I want all men in the shipyards to feel that they are working with me, not for me.” The group on facing page are, left to right, the wife of general manager of shipbuilding yard, Charlie Schwab, his wife Rana, and a niece of Mrs. Schwab.

Then, that Huber was able to connect with several alive today who have personal connections with Schwab adds a dimension biographers are not always able to find, much less consult. Schwab’s impressive business acumen and accomplishments are detailed but it’s also the character of the man that a reader can’t help but notice. Case in point, during the years 1917 to 1942 when the US was drawn into wars, Schwab’s management skills were tapped to get the most out of the Emergency Fleet Corporation. He accomplished his assigned task but more importantly as the page pair immediately above shows he insisted the proper credit belonged not to him but to the men who actually did the work.

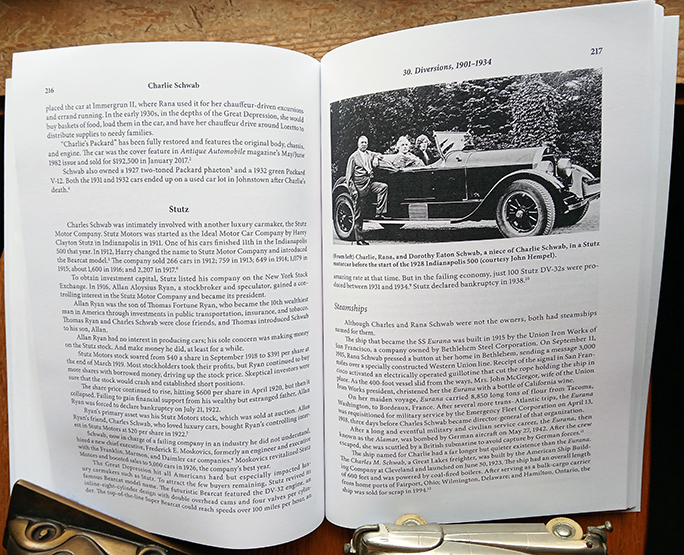

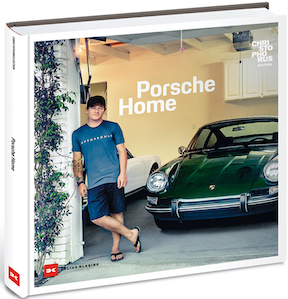

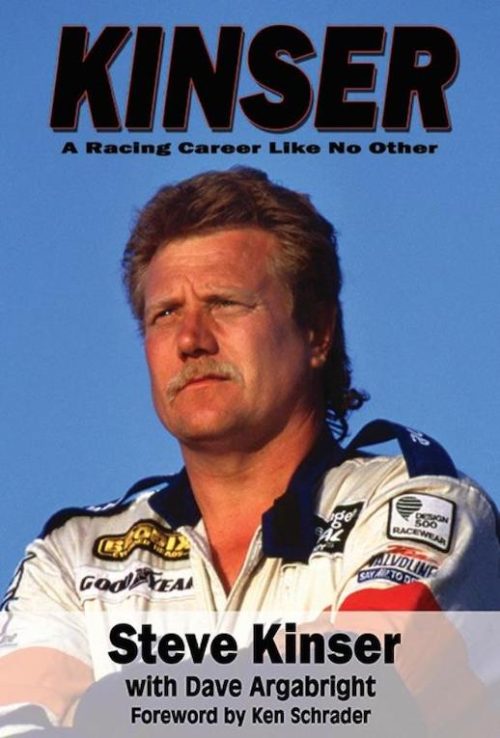

Schwab loved fine automobiles and played a role in several companies that made such. Shown here with the Stutz are Charlie, Rana, and a niece of Charlie’s. Image was taken at the Indianapolis Speedway just prior to the start of the 1928 race.

As befitting a captain of industry in those years, Schwab’s primary conveyance for long distance travel had been his two private railway cars, Loretto I followed by Loretto II. Both are extant to this day as Huber details. Schwab also enjoyed fine motorcars, Packards in particular. And, he became financially involved in the floundering Stutz motorcar company.

To be sure Charlie Schwab lived a full, rich, and engaged life. Huber brings his biography of Schwab to a satisfying close in the concluding three chapters updating the current status of places and properties associated with Charlie and/or Rana and including additional information in the two appendices.

Copyright 2024 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter