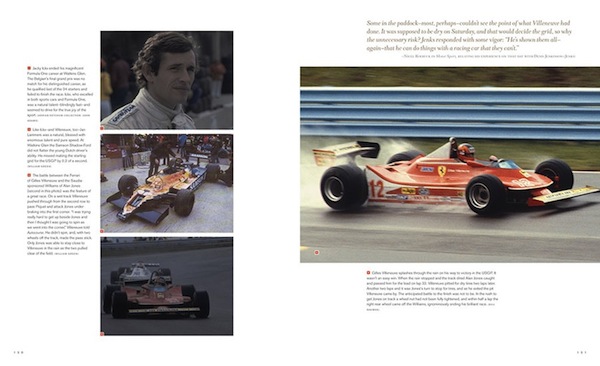

Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961–1980

Michael Argetsinger is the acclaimed biographer of racing drivers Walt Hansgsen and Mark Donohue, and he is the son of Cameron Argetsinger, who brought the US GP to Watkins Glen—who better to write the story of F1 at the upstate New York circuit? The publisher of both Argetsinger’s Donohue books is David Bull, without whom the book collections of most motor sport enthusiasts would be depleted. Here, author and publisher team up again, in pursuit of two worthy aims: to celebrate the 20 US GPs hosted at Watkins Glen, and to donate all of the proceeds from the book to the International Motor Racing Research Center, based just a few miles from the circuit. What could go wrong? Sadly, in terms of both concept and execution, a great deal.

The conceptual flaw is laid bare in Argetsinger’s acknowledgements. “I did not approach this book as the definitive history of the Formula One experience at Watkins Glen. It is principally a photographic record of those 20 years.” This seems such a shame: no circuit has hosted more US GPs than Watkins Glen, the story deserves telling in detail, and Argetsinger is uniquely qualified to tell it, but this book very probably means no one else will try now.

So, what does this non-definitive account comprise? In his foreword, Mario Andretti recalls with affection his GP debut, when he put his Lotus 49 on pole for the 1968 US GP. Then Argetsinger lays out in an introduction the arrival of road racing in the area in 1948, and the creation of the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation in 1953, and the original 2.3-mile circuit three years later.

There follow 21 chapters, the first dedicated to the Formula Libre races of 1958–1960, and the rest to each of the 20 GPs. Each chapter comprises a handful of paragraphs on the race (or, indeed, on the season, or on a development at the circuit or in the Corporation) and 10 or 12 photographs with detailed captions. A cohesive picture of a particular race emerges only slowly and in jerking fashion across text and photo captions, and there are no starting grids, results tables, index or bibliography. Nor are there maps of either the original 2.3-mile track or the 3.4-mile version introduced in 1971. Indeed, for a much clearer picture of what happened in the first 17 Glen GPs, you would be better off reading Doug Nye’s The United States Grand Prix and Grand Prize Races 1908–1977 (Batsford, 1978).

To be fair, there are some fascinating pearls that are not found in other books or in contemporary race reports. In 1964, when it emerged that the Indianapolis Raceway Park was lobbying ACCUS, the Automobile Competition Committee for the United States, to host the US GP, Cameron Argetsinger met the head of ACCUS at his New York club and outlined the costs of bringing the race to America each year. When asked if this information could be shared with “our friends in Indianapolis” Cameron produced the envelope he had already prepared with this specific purpose in mind. With admirable understatement, his son concludes the story thus: “The men cordially completed their meeting. Soon after, IRP quietly withdrew its request for the Grand Prix.” Argetsinger is also clear on the causes of Watkins Glen itself losing the race 16 years later. It is, he says, “popular fiction” to blame Bernie Ecclestone’s increased financial demands—indeed Ecclestone deferred settlement of the organizer’s fee for that final 1980 race until after the meeting and he never did collect it, even though the Grand Prix as an event was profitable to the end. Rather, it was the debt service created by the bond issue raised to pay for the track modifications of 1971 that killed the race and drove the GP Corporation into bankruptcy. Such insights are fascinating, but there is nothing like the consistent, detailed background that makes Chas Parker’s book on Brands Hatch so illuminating.

Of course, none of this would matter if the book really did excel as a photographic record of the Glen’s GPs. Argetsinger certainly had enough images to choose from—47,000!—and some of the pit lane and garage shots are indeed excellent. The best was snapped by a fan in the Kendall Technical Center during testing the day after the 1973 Canadian GP. Jackie Stewart sits on the right rear wheel of his Tyrrell and looks up at team mate Francois Cevert and McLaren driver Denny Hulme. They are discussing Hulme’s team mate, Jody Scheckter, whom the Tyrrell drivers believe caused Cevert to crash violently the day before. The power of the picture lies in what happened next. Less than two weeks later, Cevert was killed in practice for the US GP and the Tyrrell team withdrew from the race, causing Stewart to miss what would have been his 100th and final GP. When the Grand Prix circus reconvened in Buenos Aires the following January, Scheckter would be at the wheel of a Tyrrell. It is one of the most haunting, most “picture-tells-a-thousand-words” motor racing photographs I have ever seen.

But the action shots are, sadly, a different matter. For every strong image, like that of Jacky Ickx in the gorgeous Ferrari 312B on a damp track in 1970, or the very apt final photograph, of Tex Hopkins leaping high in the air, cigar clamped in mouth and checkered flag flourished aloft, there are far too many others which are poorly composed, cropped, focused, or captioned. Among those 47,000 images, did Argetsinger find only one of Andretti’s 1969 drive in the four-wheel-drive Lotus 63? This photograph comprises two-thirds of empty track, then Mario in the Lotus away on the left, partly obscured by a tree. Ten pages earlier, we see Graham Hill and Chris Amon in the 1967 race. A wide expanse of grass takes up half the image. On the grass we see the back of an advertising hoarding and three photographers. The track and the two cars, one of which is partly obscured by a photographer’s hat, form a narrow ribbon across the center of the image, and the rest is cluttered background. These sort of pictures, and those where photographers have failed to capture the whole of the lead car, remind me of amateur snapshots. They do not belong in a book of such importance, which has set the reader back $50.

Poor captioning is a further problem, and begins as early as the frontispiece, which depicts the start of the 1968 race. The bottom left hand corner is filled with the back of an out-of-focus head, and leaving the shot to the right are the rear wheel and wing of an unidentifiable car. At the center of the image lie the McLarens of Hulme, Dan Gurney, and Bruce himself, yet the caption is largely about Graham Hill. This makes no sense at all until a wider version of the photograph appears in the ‘68 chapter, where we learn that the wheel and wing are attached to Hill’s car. Who cropped the image for the frontispiece and kept the original caption? Who edited the book??

Worse comes in the 1978 chapter. Beneath a wonderful shot of Andretti in his championship-winning Lotus 79 is a pit lane image of a Williams with its upper bodywork removed, and a second team car in the background. In the caption, Argetsinger explains that Alan Jones qualified third on the grid in his Williams FW06 and finished the race in second place, concluding that it is “the reserve car” in the background. Now that is an accurate summary of the Williams team’s 1978 performance at the Glen, and they did indeed have a reserve car there that year, but the cars in the photograph are not FW06s and the year is not 1978. They are FW07s, the year is 1979, and the car in the background is the race car of Clay Regazzoni. Anyone wishing to do justice to the proud history of the US GP at Watkins Glen should surely know that a JPS-sponsored Lotus 79 and a Williams FW07 could not have taken part in the same race.

The nadir is reached seven pages later. Gilles Villeneuve is shown powering his Ferrari out of a left-hander chased by a Williams that, writes Argetsinger, is driven by Jones, though it is actually Regazzoni and, far worse, they should be leaving a right-hander—the image has been flopped! Think about that: someone scanned the slide or transparency the wrong way round (or flopped it in the computer), someone page-set the photograph the wrong way round, and someone edited that page, yet not one of them spotted that the numeral “12” on the bodywork is reversed. This is not the David Bull Publishing we are used to.

The book also suffers in failing to use many distinctive images associated with Watkins Glen down the years. There is no picture of Jim Clark winning in 1966 with the Lotus 43, the only time BRM’s cumbersome H16 engine won a GP. There is an image of the engine, yet Clark’s only appearance in the chapter is restricted to his left eye, nose and mouth, on the extreme edge of an otherwise excellent shot of Lotus boss Colin Chapman holding the victory bowl aloft. Two years later, Andretti’s duel with Stewart for the lead of his debut GP ended when he was slowed by his nose cone coming apart and his wing dragging on the track. It is an abiding image of the 1968 US GP, just as Eugene Lewis’ shots of Graham Hill’s accident are abiding images of the 1969 race, but none of them appear in this book. The story of the final US GP at Watkins Glen, when Bruno Giacomelli led early on in the bulbous Alfa Romeo but retired, and Jones came through to win from 12th place after running wide at the first corner and throwing up plumes of dust, is brilliantly captured by the Jeff Hutchinson image which adorned the cover of the following week’s Autosport. This is a Haymarket magazine and as such, the photograph may well reside in Haymarket’s LAT archive but, once again, it is not in the book.

And therein, perhaps, lies the cause of this book’s flaws. In deciding to devote every cent of the proceeds to the IMRRC, was there an obligation to minimize production costs? Was access to the major international photo archives ruled out? Were Bull’s best people on other projects? Was Argetsinger’s research and writing time-restricted?

It pains me to be so negative about this book. Argetsinger and Bull are highly respected in the world of motor racing literature, and the book was published with a worthy cause in mind. But the stark truth is that this would be a flawed book even if these men’s high standards were not applied to it. Far better, surely, to have devoted more time to the project, spent more money on it, and given only a portion of the proceeds to the IMRRC—consider Michael Oliver’s excellent Tales from the Toolbox: 40% of the royalties from it were donated to the Grand Prix Mechanics Charitable Trust. In this way, we might after all have enjoyed the definitive book on the US GP at Watkins Glen, the book that will now probably never be written.

Copyright 2012, Paul Kenny (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

It must be mentioned that the book won a Gold Medal in the 2012 Independent Publisher Book Awards. Since its founding only six years ago, over 4500 books have received IPPYs—and the word “award mill” presents itself. In view of the objective shortcomings enumerated above, it devalues both the awardee and the awarder if a flawed book is singled out for distinction.

Incidentally, 2012 is the same year that Janos Wimpffen’s Elva book (same publisher) won a mere bronze. This would be a gross injustice—IF the “judges” actually knew enough about the contents of the books they are judging and thus the award actually meant something.

I would suggest that Mr. Kenny reviewed the book that he wanted to read, not the book that was actually in front of him. He is, of course, fully entitled to his opinion of the book, as to whether it is good, bad or different, that being the role and function of the reviewer and the critic. That said, when Mr. Kenny begins with the statement from the author clearly defining the limited the scope of the book and then proceeds to lambast the author and the publisher for not providing the book that he, the reviewer, wanted to read instead, well, while I fully understand the impulse to do so, I also think that one could have gone about it somewhat differently.

Some of the criticism of the book is certainly warranted and justified, something that I do agree with and think should be mentioned. There are more than a few flaws — Mr. Kenny’s favorite word in the review — to mar some aspects of the effort, with those related to its production such as reversed photo cited and some of the captions being, unfortunately, the all too usual bane of even the most careful and diligent of authors and publishers. Not an excuse, but simply an observation of an all too frequent problem in the publishing business.

It is interesting that Mr. Kenny states that the basic and fatal flaw — that word again — of the book that of the altruism of Mr. Argetsinger and the publisher to support the International Motor Racing Research Center located at Watkins Glen and among the very few such efforts worldwide. Neither it nor the few other such efforts operate solely on the good wishes and kind thoughts of those wishing them well. They need money to keep the doors open and the internet portal open.

This causes me to return, for the moment, to the book that Mr. Kenny wanted to read. What Mr. Kenny wanted to read was a book aimed at the motor racing nerd, the enthusiast who is generally quite long on information and far more often than not quite short on knowledge. That such a book should be written — and, preferably, by Mr. Argetsinger — I would certainly agree, but its appeal would certainly be far more limited than the one that was written, one that has, perhaps, more appeal to the general public.

To raise funds by selling such books, the books have to have an appeal beyond the dozens of enthusiast nerd and be priced at something that is reasonable enough to have people willing to shell out the money for such a book. Life is full of compromises and, like or not, so is the publishing business.

It is fair to aim tungsten-tipped, depleted uranium, 120mm armor-piercing discarding sabot rounds at authors and books (and publishers by extension) that simply get it wrong or muddle it to such an extent that they might as well get it wrong or any of a number of such related sins if that is what is either in the book or was intended to be in the book. It is quite another to ignore the book at hand and compare it to the book that the reviewer would have written.

Again, Mr. Kenny is fully entitled to his opinions and views, whether one agrees or disagrees with them is largely irrelevant. There is some agreement on my part with aspects this review as stated, but I would suggest that for Mr. Kenny to despair, “We might after all have enjoyed the definitive book on the US GP at Watkins Glen, the book that will now probably never be written,” is the basic flaw of his review.

Yes, it might have been nice to have such a book, but that was never the purpose of the work at hand. Nor do I think that Mr. Kenny’s lament is necessarily the case regarding the book he wishes regarding Watkins Glen. I happen to believe that such a book will emerge, perhaps not in the next year or two, but that it will be written and published.

Dear Mr Capps

Many thanks for your reasoned response to my review.

Essentially, I had two criticisms of the book. First, that it was restricted in focus and second, that its execution was poor. You take exception to the first one, and you have every right to – you say that I didn’t review the book at hand.

I regret it if it appears to you that I wrote a review of a book that doesn’t exist. That first criticism of mine is based on my deep regard for the US GP at the Glen. As a boy growing up in ’60s England I always looked forward to those races – the 108 laps, that distinctive run-off outside the exit of The 90, even calling a corner The 90! Now that might make me a nerd, but on the very day that doubt has been expressed about a 2013 US GP at Austin, those 20 races at the Glen matter more than ever. Watkins Glen is the only real home the US GP has ever had, and the 50th anniversary of the first race was the perfect opportunity to celebrate that fact.

I’m simply sad that this book is a massive missed opportunity, and that men of the talent of Messrs Argetsinger and Bull missed it. I sincerely hope that you are right and that the definitive account of those 20 races at the Glen will see the light of day. My pessimism on that point is influenced by the decline of the written book and the closing of specialist book sellers. I fear that, even when an upturn comes in the global economy, it will be very hard to argue the case for another book on the subject.

Do please note that, at the conclusion of my first criticism, and having highlighted two of the pearls that are contained within the text, I write ‘none of this would matter if the book really does excel as a photographic record of the Glen’s GPs.’ And I go on to review the book at hand.

And I maintain that the book at hand is a disappointment.

Best wishes

Paul Kenny