Wayne of Gotham

Postmodernism is a happy conundrum. Get a dozen postmodernists, painters, writers, theorists, critics, what-have-you, in a room together and ask them to define the concept. For your trouble, you will get a dozen definitions, and these will be convoluted, obscure, obtuse, abstruse, abstract, circumspect, circumvented and hedged. You will also get a dozen denials: Not me! I am not really a postmodernist. At all. But since postmodernism has been kicked around the block for decades now, there must be something to it. A quick primer: postmodernism surfaced in architectural theory somewhere right before or after the Second World War. It was, perhaps, a way to go beyond modernism, a way of championing a style that slyly, knowingly, incorporated various preceding styles into a single and personal statement. Or just as likely—and here is but one facet of the conundrum—a multiple and collective statement. Postmodern theory and criticism began percolating throughout academia in the 1950s and, in painting, came to a decisive, quick paradigm shift in the 1960s when the likes of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein turned modern art on its head, the result being, well, postmodern. Some say postmodernism is a counter to and a rebuke against modernism; others suggest that it is simply an extension of the modern movement. So: Pablo Picasso is modern, Warhol postmodern. T.S. Eliot is modern, Rita Dove postmodern. Le Corbusier is a modern architect as Frank Gehry is a postmodernist. In novels: D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce modern; Don DeLillo and Haruki Murakami post-. If you are a movie buff, you would consider François Truffaut’s Breathless very modern indeed, but you would certainly agree that Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction is postmodern to the nth degree. Realizing that a hatful of examples may only add to the perplexity and not lead to any definitive understanding, a general overview is in order.

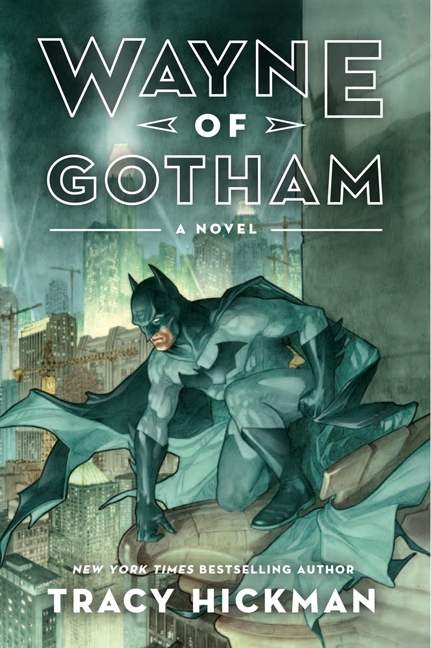

Postmodernism is self-referential. It likes to feed upon itself , a scorpion biting its tail. It blurs any distinction between popular and fine art. It has developed a strong taste for genre literature: science fiction, Westerns, bodice-rippers, procedurals; it also folds within itself a genuine admiration for comic books, television, media stars, pornography, B-movies, radio serials and popular magazines. Postmodernism likes puns and palindromes. It relishes obscurity. Ambiguity and irony are staples. Often postmodern art and literature enjoy taking the viewer or reader behind the scenes, readily acknowledging and celebrating artifice, a showing of just how it is done. Now it is true that modernism has integrated within its purview at least some of these things. The difference? To expand an above example, yes, Eliot, in Prufrock, leans in the direction of some postmodern ideas, but, even with its brief flash of smirk and wry humor, the poem is overall dire and self-aggrandizing; whereas in Dove’s Hattie McDaniel Arrives at the Coconut Grove, even with the indisputable seriousness, substance and heartbreak of its theme, there is an undercurrent of humor, a sharp elbow in the ribs and a long road from Eliot’s haughty drawing room to the Klieg lights of Hollywood. Another fast example: Willem de Kooning, although experimentally loosey-goosey, was so damned serious, while Warhol, in his deadpan manner, reveled in the humor and the self-parody inherent in his work. And all of this, finally, brings us to an appreciation of what may be the ultimate postmodern novel: Tracy Hickman’s Wayne of Gotham, based upon Bob Kane’s The Batman—who (The Batman, not Kane), by the way, is nearing his seventy-fifth year.

In his book, Batman Unmasked/Analyzing a Cultural Icon, an academic study written for a popular audience, Will Brooker asks these questions: “What does the Batman signify in this cultural moment? What wider context surrounds this particular inflection? What different interpretations govern this meaning, and within which matrix of imposed, ‘dominant’, delimiting and counter-definition is it situated?” Abstruse? Obtuse? Perhaps—but Wayne of Gotham bundles these questions and tenders a blanket rejoinder in its format as a work of contemporary crime fiction. (Remember: The Batman is not a superhero per se; he has no super powers; he is a crime fighter, and, notably, he is a detective.) Brooker argues that there are six irreducible attributes of the mythos of The Batman: “Batman is Bruce Wayne, a millionaire who dresses in a bat-costume and fights crime; he has no special powers but is fit and strong, and very intelligent; he lives in Gotham City; he fights villains like the Joker; he fights crime because his parents were killed when he was young; and, lastly, he is often helped by his sidekick, Robin.” I would amend at this point in time “millionaire” to “billionaire” and I would suggest, because of much of the Batwork of the last few decades, that The Batman “sometimes” is helped by Robin; but besides these two minor cavils, I believe Brooker to be sound, right on the money. Wayne of Gotham incorporates five of these basic constituents, and alludes to the sixth: Robin is absent in the novel, but, posing as a gamekeeper on his own estate, Wayne calls himself Gerald Grayson, and, as is well known, Grayson is the surname of the first and most popular Robin, The Batman’s sometime sidekick. (There were other Robins, one of them was a young woman, another had been killed off by a telephone vote of Batfans, but these are stories for another day. I have already circumvented, in my postmodernly way, too long the target of this review.) Another nod to postmodernism is the fact that in this book, we find that Martha Wayne, Thomas’ wife, Bruce’s mother, was originally a Kane. What may be Hickman’s most clever device, all said, one that helps cement another layer to The Batman’s mythology, is his fleshing out of Patrick Wayne; introduced elsewhere in The Batman chronology, he is Thomas Wayne’s father, Bruce’s grandfather. Hickman also is sharp enough to involve Thomas, a physician and medical researcher, an honorable and upright character in most of the annals of The Batman, in a well-meaning but ultimately malevolent, destructive eugenics experiment, one that goes horribly awry.

In his book, Batman Unmasked/Analyzing a Cultural Icon, an academic study written for a popular audience, Will Brooker asks these questions: “What does the Batman signify in this cultural moment? What wider context surrounds this particular inflection? What different interpretations govern this meaning, and within which matrix of imposed, ‘dominant’, delimiting and counter-definition is it situated?” Abstruse? Obtuse? Perhaps—but Wayne of Gotham bundles these questions and tenders a blanket rejoinder in its format as a work of contemporary crime fiction. (Remember: The Batman is not a superhero per se; he has no super powers; he is a crime fighter, and, notably, he is a detective.) Brooker argues that there are six irreducible attributes of the mythos of The Batman: “Batman is Bruce Wayne, a millionaire who dresses in a bat-costume and fights crime; he has no special powers but is fit and strong, and very intelligent; he lives in Gotham City; he fights villains like the Joker; he fights crime because his parents were killed when he was young; and, lastly, he is often helped by his sidekick, Robin.” I would amend at this point in time “millionaire” to “billionaire” and I would suggest, because of much of the Batwork of the last few decades, that The Batman “sometimes” is helped by Robin; but besides these two minor cavils, I believe Brooker to be sound, right on the money. Wayne of Gotham incorporates five of these basic constituents, and alludes to the sixth: Robin is absent in the novel, but, posing as a gamekeeper on his own estate, Wayne calls himself Gerald Grayson, and, as is well known, Grayson is the surname of the first and most popular Robin, The Batman’s sometime sidekick. (There were other Robins, one of them was a young woman, another had been killed off by a telephone vote of Batfans, but these are stories for another day. I have already circumvented, in my postmodernly way, too long the target of this review.) Another nod to postmodernism is the fact that in this book, we find that Martha Wayne, Thomas’ wife, Bruce’s mother, was originally a Kane. What may be Hickman’s most clever device, all said, one that helps cement another layer to The Batman’s mythology, is his fleshing out of Patrick Wayne; introduced elsewhere in The Batman chronology, he is Thomas Wayne’s father, Bruce’s grandfather. Hickman also is sharp enough to involve Thomas, a physician and medical researcher, an honorable and upright character in most of the annals of The Batman, in a well-meaning but ultimately malevolent, destructive eugenics experiment, one that goes horribly awry.

This experiment, along with its complications, becomes an important and parallel back story to the present day plotline, and, thus adds yet another cipher into the ever expanding Batman Universe. As is often found in crime fiction, Hickman uses place, time and date chapter headings, beginning in September of the year 1953, when a fifteen year old Thomas is being berated by his father. The novel shifts back and forth between past and present. As noted, The Batman is presently a septuagenarian, but in an ongoing, very postmodern (and commercial, it must be said) exercise, the ages of the characters, the timeframe of the stories, and the continuity of the overall, epical, far-reaching storylines become plastic, ready to shift easily to accommodate any of the multitudinous telling and retelling of his adventures. Hickman’s choice of the timeframe for this book is a good one. By starting the tale in the 1950s, Hickman invites such nostalgic details as Formica tabletops, Bettie Page, beatniks, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, pink cardigan sweaters, ponytails, and perhaps the best of all, Thomas’ inheritance of his father’s Lincoln Futura, “a second version” of “a concept car” that Patrick had “financed . . . from the Ghia plant in Turin.” Although Thomas enjoys using this car, the Plexiglas “double-teardrop top . . . acted like a greenhouse under the sun.” Another very clever reference is to the building of the real-world Winchester house, a rambling mansion in San Jose, California, that was in continual construction, with blind passageways and stairwells erected to confuse, hinder and appease the ghosts of the victims of Winchester rifles. Ingeniously, Hickman parallels this with the building of the Arkham Asylum, thereby adding a bizarre plausibility to this vast, elaborate, labyrinthine, Gothic structure, Gotham’s citadel for the criminally insane. Hickman gets the details right.

And by setting the main storyline in the mid-twentieth century, Hickman also gets to update the technology of the Batcave, the Batsuit and the latest edition of the beloved and ever-evolving Batmobile: “Batman reached out with his gloved hand, tapping at the newspaper reference in the air. The window was instantly replaced with a vertical frame and a scan of a page from the Globe. . . .” Later, in another chapter, Hickman mentions the Batsuit’s “subsonic imaging system” and explains “how the exomusculature of the Batsuit stiffened, supporting [The Batman’s] frame as it accelerated him upward.” Even the cape is proactive and protective, this new costume being a far cry from The Batman’s purple and black circus tights found in earlier comics. The present Batmobile is fitted with onboard holographic displays and a flexible outer skin that can expand and contract as needed. Also included in the novel is an updating and judicious use of a familiar roster of supporting characters: Harley Quinn, aka Harleen Quinzel; the Wayne mansion’s butler Alfred Pennyworth (and in the flashbacks, his father Jarvis Pennyworth); the gangster Julius Moxon; the evil Spellbinder; the heroic, if honestly human, policeman James Gordon; and, how could Hickman not introduce The Joker into the mix? There are others. Hickman also makes good use of a massive and looming Wayne mansion, a dark and sinister Gotham city, abandoned subway tunnels, and a hidden laboratory in a deep, forgotten subcellar of the aforementioned Arkham Asylum. Also, the novel has enough action and derring-do to satisfy, enough cliff-hanging and revelations to intrigue. Look for a doubled surprise at the end. But as much as all of this resonates throughout the decades of The Batman and his Universe, I cannot help asking how the story would play out to the uninitiated. As unbelievable as it must seem, there must be some readers out there who have not heard of The Batman, or perhaps have only a sketchy knowledge of The Dark Knight. How would they approach this novel? Is Hickman’s skill large enough to draw in, entertain and satisfy those not conversant with the history and mythology of The Batman? Can the novel stand alone? Because of the ubiquity of this fictional phenomenon—Brooker believes that The Batman’s infiltration into world culture is nearly boundless—these questions become virtually moot.

Postmodern then? Absolutely. Great literature? Well, there’s a postmodern poser for you. If not The Great Gatsby, Wayne of Gotham can at least stand unabashedly among the better examples of crime literature, Elizabeth George, Scott Turow, Colin Dexter, Raymond Chandler; and it is far superior to the superhero novels that have come before. Try it. Be not afraid.

Postmodern then? Absolutely. Great literature? Well, there’s a postmodern poser for you. If not The Great Gatsby, Wayne of Gotham can at least stand unabashedly among the better examples of crime literature, Elizabeth George, Scott Turow, Colin Dexter, Raymond Chandler; and it is far superior to the superhero novels that have come before. Try it. Be not afraid.

Copyright 1013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter