The Story of Music, From Babylon to The Beatles

How Music Has Shaped Civilization

“Whatever music you adore—Monteverdi or Mantovani, Mozart or Motown, Machaut or Mash-up—the techniques it relies on did not happen by accident. Someone, somewhere, thought of them first.”

It was as if I had met Howard Goodall a few years back, perhaps in the late evening in some dark, wood-paneled taproom, and said to him, being on a first name basis after the second pint, “Howard, I wish there were a book about music for someone like me. Honestly, what I listen to most days is a combination of rock, blues and jazz from the mid-twentieth century. But I know a little bit about classical music—I would recognize a Bach Brandenburg or one of the Four Seasons—although I have spent more hours in life listening to Frankie Vali than to Vivaldi.” Howard would nod his head. “And,” I would continue, “I have a basic idea of music notation and even less of an idea of music theory, and most books I have read still keep me at sea. I have in my head a rough idea of the history of music, but the details in there are sketchy at best. Wouldn’t it be great if someone would write a book that would explain all of this in a way that was literate but understandable, thorough yet easily read?” After last call, Howard would go home to begin to write The History of Music just for me! And for several thousand others.

Such fantasy aside, Goodall comes through. With a prose that is both academically sound and nimbly readable, with humor and sagacity, the book moves on like—well, like a pleasing, well-constructed symphony. As it is chock full of facts, personalities, musical theory and history, it would be difficult, after the final closing, to recall every single detail but the reader is left with a lingering grasp of the whole, a feeling of being grounded, a notion of the connectedness of it all, an assurance that it all makes sense.

Early on Goodall defines his parameters, noting that he will be discussing the heart of the music of the West, what has come to be known as classical. We learn of how the ancients regarded and utilized music, how various modes and scales and systems of notation went in and out of favor, evolved and substantially crystallized into what we have now. He discusses how the invention and improvement of various instruments, pointedly the piano-forte, changed not only how music was played, but also how it was conceived and composed. Goodall discusses the division of the elite and the common or folk musics, and tells us that in his lifetime Mozart was of course well known—but only by a very small percentage of the populace. In our age of virtually unlimited sound reproduction and ubiquitous availability, he reminds us that back in the day a music lover might hear a favorite piece only a few times in a lifetime. One idea reappears throughout, the idea that those who are today considered the stellar composers were not necessarily the most original, but rather those with the ability to synthesize and make their own the work that had come before. There are passing references to the music outside the scope of Western music, and explanations of how much of this was absorbed in this mainstream, and how, naturally, this absorption grew deeper as we moved into the modern then contemporary age.

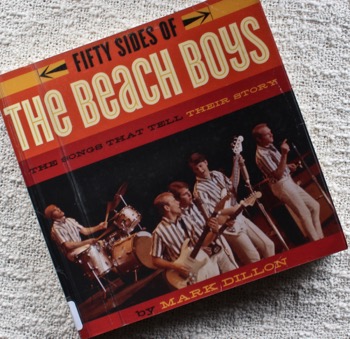

Goodall is a practicing composer and musician and this adds gravitas to an already weighty and seemingly inexhaustible body of knowledge. One gets the idea that he carries all of this in the front part of his mind, readily and easily retrievable—that if asked a specific question, no matter what area of the subject, the man would expound and expand in a sensible and clear manner. His story of how in the middle of our last century, classical music became trapped in a double bind exemplifies Goodall’s comprehensive grasp of his subject. In concert halls, classical music (which is a popular misnomer, the word “classical” amorphous in its several connotations) looked back centuries to offer concertgoers, most of whom formed a cultural elite, comfort and familiarity. Simultaneously, contemporary composers working in the classical milieu were creating new music that was theoretical, experimental, perhaps unlistenable and rarely performed. With keen originality, Goodall contends that the real heart of classical music during this time—and a few decades before—lay in music composed for film. He makes a strong case. Eventually jazz, blues, folk and world music fold into the mix as does the game-changing rock-and-roll. Goodall has good words to say about Stevie Wonder, Paul Simon and The Beatles. The subtitle of the book wobbles as Sting and hip-hop are eventually discussed, but alliteration holds out a strong temptation, even to someone as gifted as Goodall. There is little to say about the book that is negative, although the marked score on page 127 is unclear, making Goodall’s explanation difficult to follow, and I did find a typo that caused momentary confusion—but these are hardly worth the mention.

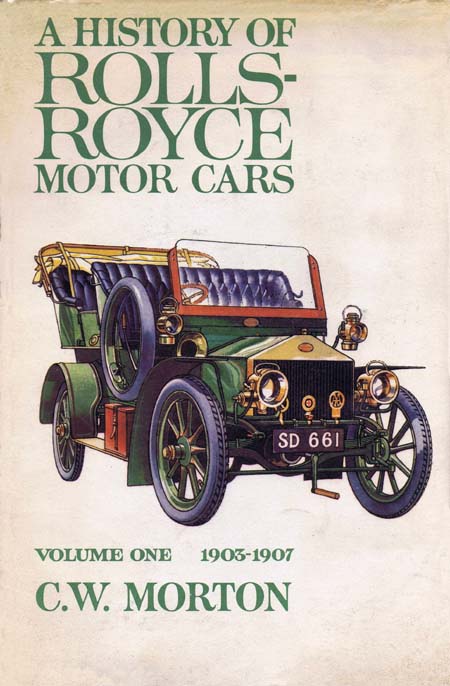

What is worth mentioning, however, is that The Story of Music has sixteen contiguous pages of full-color illustrations, imaginatively chosen, diverse, and attentively arranged. A reviewer for The Daily Telegraph opined that this book “will not only win prizes butchange lives.” To argue against this would be to engage futility.

Copyright 2014, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter