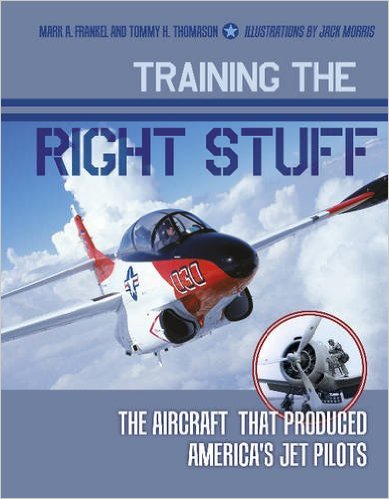

Training the Right Stuff: The Aircraft That Produced America’s Jet Pilots

by Mark A. Frankel & Tommy H. Thomason

by Mark A. Frankel & Tommy H. Thomason

“Unless the subsequent pitch down and loss of lift is counteracted by quick and appropriate application of power and pitch (the instinctive and totally inappropriate response to the nose coming up is forward stick) then the next arrival will either be an even bigger bounce or the collapse of the landing gear.”

While the above is not, really, rocket science, the quote does illustrate that what saves the day are training, repetition, and the incremental changes in instinctive behaviors that should result.

The quote also shows that both authors have a fine appreciation of airmanship—in Frankel’s case because he studied aeronautical engineering (although his Navy career in the JAG Corps was more of a desk job) and he is a licensed private pilot, and Thomason was an aeronautical and flight test engineer with a full deck of private and commercial licenses.

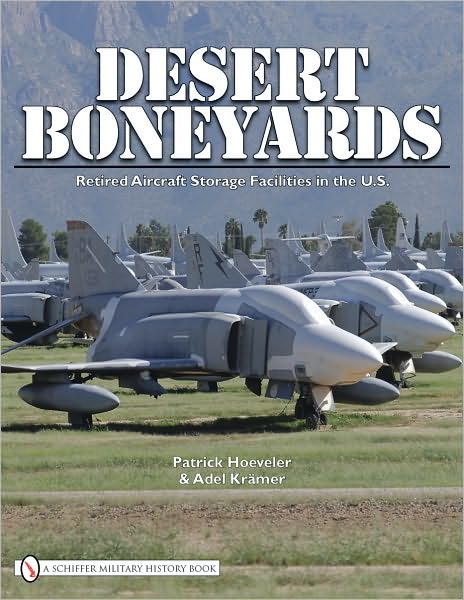

Before looking at the contents proper, a different matter deserves to be raised because it sheds light on a quite uncommon commitment to quality. This book doesn’t just tell an interesting story, it is itself an interesting story—in regards to the making of books. This publisher’s books have a reputation for solid construction and high production values—paper, printing, binding and such. When we saw an advance copy in June we were tempted to remark that the color photos looked overboosted, a bit garish—nothing catastrophic, just not quite on the money. We do know that there are many moving parts to the image manipulation and printing processes and also that the source material may have been poor . . . but the reality is that many readers may have never noticed. And then a letter from the publisher arrived advising that the image reproduction did “not meet with [their] standards” and that the book would be withdrawn from further sale, and offering customers not only a free replacement copy in a few weeks but even a prepaid postage label to return, if desired, the offending copy. Such an action is quite without precedent and one can only praise publisher Peter Schiffer for caring what he puts his name on. (Customers should reward such dedication to quality by renewed loyalty to the house!)

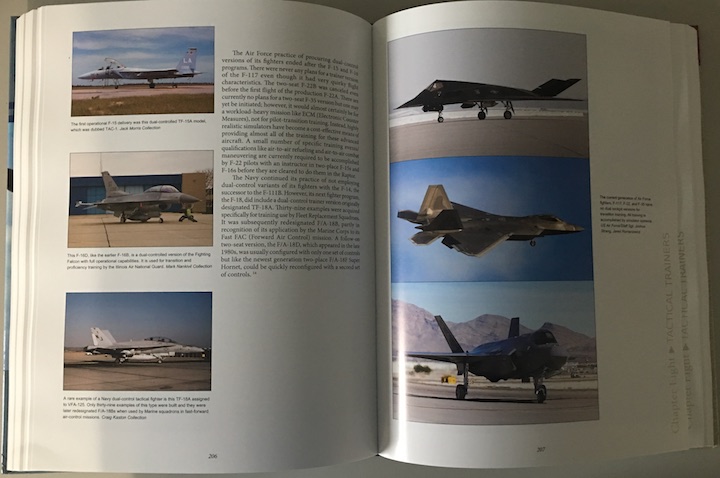

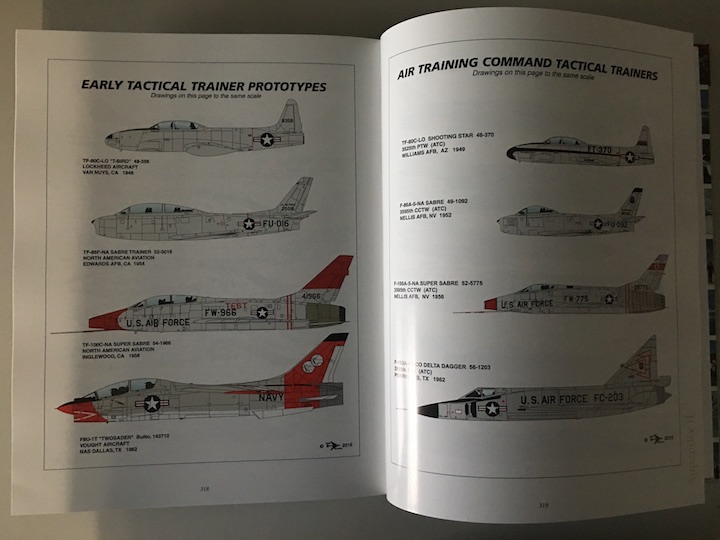

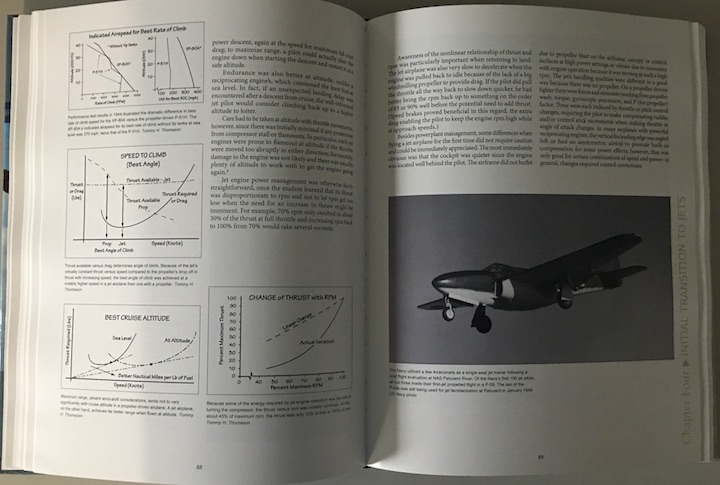

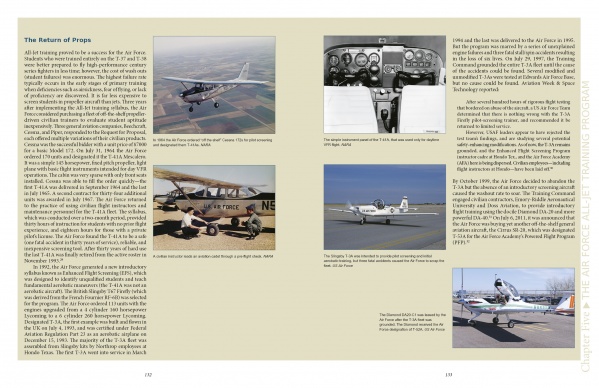

The book advances the story line by focusing on the hardware—the actual flying apparatus—and discusses pilot skills and the inner workings of the training command only insofar as it has a connection to the changes in technology and flight characteristics of the aircraft as the US military transitioned into the jet age, beginning with the ubiquitous T-28. A closing chapter offers a quick synopsis of civilian-owned ex-military trainer aircraft and here the clock is turned back all the way to Stearman biplanes. If all this whets your own appetite to learn to fly, Appendix I “Learning to Fly” briefly enumerates what steps a student would go through from ground school to first solo. A second Appendix describes and illustrates markings and paint schemes (by USAF Col. Jack Morris) of Navy and Air Force trainers through the years.

Readers new to the subject should probably begin with the Glossary or even the Index just to gauge how new/foreign the material might be. While the book is, on the one hand, easily approachable to anyone with even a modicum of interest it is also seriously detailed to satisfy its claim of being “a comprehensive study,” with all the data and techno speak this implies (even chapter notes). Coverage extends over some seven decades and into 2016 so the book was not only utterly current at the date of publication but also quite alone in covering this subject this way.

If the subject matter seems esoteric or irrelevant to some, consider that the pilots trained on the first US airplane, the Wright Flyer, were unable to operate the second one, the Curtiss, not only because the control layouts were not standardized but the training syllabus wasn’t the same either. We’ve come a long way since then.

Copyright 2020 speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter