Vinyl Freak, Love Letters to a Dying Medium

“Anyone following Ms. Galas who hasn’t heard this is missing the pinnacle of her achievement—terrifying sidelong suites of multitracked vocal hysteria, some hushed, some screeched. On the label run by Larry Ochs of NOVA Saxophone Quartet—thank goodness he put this out.”

—p. 188 (emphasis added)

Why is it that only men—with few exceptions—are Vinyl Freaks? In John Corbett’s acknowledgements, all of his vinyl pals are men. In the book on Shellac Freaks, Do Not Sell at Any Price, Amanda Petrusich, after extensive searching, located but two women besides herself involved in the hobby. Photographs of smiling, sometimes sheepish collectors, heavily laden shelves of records behind them, gingerly holding a rare and valuable find, inevitably portray someone of the male persuasion. I have often mused that it has something to do with the fact that men cannot have babies—but that, obviously, is too weird, too facile, too unsupportable.

About a dozen years ago, when I still had the jones for thumbing through racks of LPs and 45s, I wandered into a dealer in used vinyl down at Point Pleasant Beach, New Jersey: a large room chock full with rows upon rows of shelves, with boxes upon boxes of records underneath the shelves, and with stacks upon stacks of vinyl in various corners. Dark, dreary. An undercurrent of mildew and fusty odors. This was a turning point. I felt overwhelmed and somehow disgusted. After that, my addiction waned considerably, although to this day I rue that I did not pick up there Carl Wilson’s coveted first solo LP. Several years before that encounter I had found myself in another New Jersey used record exchange, a place where, as the owner subtly hinted, one could obtain marijuana in exchange for the right kind, read saleable, vinyl. Here I was offered a 45 RPM, seven-inch recording of The Kingsmens’ Louie Louie on the original label, Jerden 712. Although I had already at least one copy of the Wand release and also had the song both on various LP and CD compilations and the Kingsmen LP, and although the Jerden copy would have set me back around $70, I . . . considered the purchase. I verily coveted this icon, this historic artifact. But sanity and practicality got the better of me. The fact that I can still vividly recall these occurrences. . . .

But my vinyl addiction (Corbett uses the term throughout the book without irony) is nothing, nothing compared to that of our author. Luckily I have been going through self-rehab these last several years—although you may want to take a look at The Whole Maghilla right here on Speedreaders.

Corbett begins his story when he was three and listening repeatedly to his then favorite vinyl record, A Day in the Life of a Dinosaur. I was around that age when I listened repeatedly to the Giggly Giggly Pig 78 (“Oink, oink, oink, the giggly, giggly pig. . . .”) on a very neat kiddie machine with its single round speaker neatly encased in filigreed metal and mounted on the tone arm above the needle.

Mostly the book is comprised of reprints from Corbett’s Downbeat columns written somewhat before, during, and after the fairly recent resurrection of the “dying medium.” He certainly has the chops for this gig as he is a musician, a teacher, a curator, a record producer, and has traveled the world over searching for the unusual and the singular recording. Although there is evidence throughout the book that he collects and has a working knowledge of other genres, his focus here is jazz. Most of his reviews cover the usual jazz styles such as Dixieland, bebop, post-bop, hard-bop, cool and mainstream, but throughout he exhibits a predilection for free jazz and various electronic styles: musique concrète, noise music and music from the Fluxus group. Think Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, John Cage, Pierre Schaeffer, and Yoko Ono.

These reviews are based on Corbett’s contention that vinyl is important, that there exists a large body of work all but unknown to the general listener, and that these obscurities should be given a wider audience. He pleads that each and every album should be rereleased, preferably on vinyl but at least on CD, and thereby given wider circulation. Corbett touches upon the difference, the usefulness and the attributes of the various mediums. Naturally vinyl wins the prize, Corbett even acknowledging, even defending, the inherent detriments of static, clicks, skips and pops: “As with a good pair of denim jeans or a leather bag, wear is not all bad. . . . When vinyl gets lightly scratched, up to a point it acquires a patina. . . .” General listeners may find the reviews fascinating in themselves, perhaps prompting them to go beyond their everyday listening. For the fanatics, the reviews may instill some self-satisfaction and a sort of vindication if they are already aware of and perhaps even own the targeted LP or 45—or cause in them a lingering dissatisfaction followed by a burning need to track down and acquire it if they do not. Each review is followed by a contemporary postscript reporting the details of any rereleases or lamenting the fact that there are none.

The reviews reinforce the fact that this man’s knowledge is deep, all-encompassing. When deciding how to approach Freak, I was tempted at first to offer a dose of hard skepticism believing then that no one, no matter how good, how smart, could ever assimilate this much material and be able to discuss it cogently, exploring details within details. Over one hundred obscurities are showcased, some being obscurities by someone well known while many others are obscurities recorded by obscure musicians. Does this man truly have a running, working knowledge of this much music? But then I thought of Phil Schapp, the American jazz DJ who, since 1970, has been the host of jazz programs on the Columbia University radio station WKCR. He has lectured and written extensively on Charlie Parker and others. Between records he talks of the music at length and with many circumlocutions, and it seems that he is talking without notes. His knowledge of recordings, recording dates, recording studios, record producers, catalog numbers, club dates, and various sidemen flow cascading from his synapses into the microphone and into the air. So if Schapp can do this, why not Corbett? Such focus, determination, assimilation and attention to detail, even if somehow bizarre and immoderate, must be accepted and respected. This is what he knows; this is what he does.

Corbett has a great appreciation for the musician Sun-Ra, and the book includes an accounting of how, with a hernia and in pajamas, he paid for, supervised, and contributed to the excavation and removal of stuff from the vacated former home of the late Alton Abraham, Sun-Ra’s manager. The text reads as a nexus of Hoarders, Storage Wars and the opening of King Tut’s tomb. Record albums, original artwork, contracts, notebooks were all piled together with the more mundane material found in anyone’s daily living. Corbett wanted it all. He spent more money than he could afford to transport and store it all. He spent countless hours sorting and appraising. He had to decide what to keep for his personal collection and negotiate for the best possible repository for the remainder. (And here a good word must be said for Terri Kapsalis, Corbett’s wife, who apparently condoned, supported, enabled, and championed his various addictions.) This part of the book is welcomed as it relieves the inherent tedium found in pouring through one review after another.

Corbett has a great appreciation for the musician Sun-Ra, and the book includes an accounting of how, with a hernia and in pajamas, he paid for, supervised, and contributed to the excavation and removal of stuff from the vacated former home of the late Alton Abraham, Sun-Ra’s manager. The text reads as a nexus of Hoarders, Storage Wars and the opening of King Tut’s tomb. Record albums, original artwork, contracts, notebooks were all piled together with the more mundane material found in anyone’s daily living. Corbett wanted it all. He spent more money than he could afford to transport and store it all. He spent countless hours sorting and appraising. He had to decide what to keep for his personal collection and negotiate for the best possible repository for the remainder. (And here a good word must be said for Terri Kapsalis, Corbett’s wife, who apparently condoned, supported, enabled, and championed his various addictions.) This part of the book is welcomed as it relieves the inherent tedium found in pouring through one review after another.

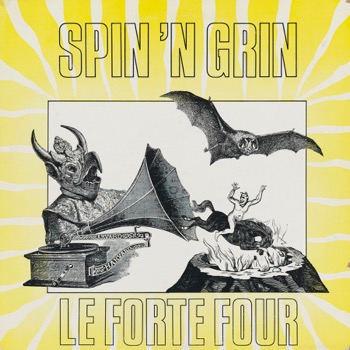

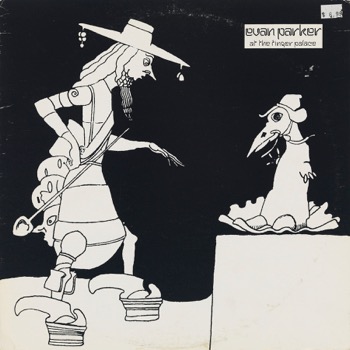

The prose throughout is respectable if not inspiring, and Corbett’s intermittent attempts at being so hep or slyly humorous too often fall flat. That the book has no index is surprising as it is published through Duke University. The color illustrations of album covers, many of them entertainingly peculiar, add to Freak’s desirability—as does Michael Jackson’s (presumably not that Michael Jackson) frontispiece cartoon and Mauricio Kagels’s clever cover photograph. Is there a market for this book? Anyone (any male person?) over the age of forty-five (and some younger) has most likely at least some interest in vinyl, but the majority would be drawn to pop and rock music rather than to jazz. So for those with universal musical tastes and those who are incurable vinyl junkies—yes. For rock ‘n’ rollers—maybe. For collectors of classical and opera LPs—mmm . . . maybe. For unadulterated horn-dog vinyl jazz freaks—indubitably.

Copyright 2017, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter