The Art of NASA: The Illustrations That Sold the Missions

by Piers Bizony

by Piers Bizony

“The realms occupied by clever, forward-thinking humans might become interplanetary—and one day, interstellar. The many books, magazines, and NASA press kit visualizations of our possible future in space, created by all kinds of artists whose names I never knew at the time, acted on my young mind like matches in a firework factory. That’s why “The Art of NASA” has been such an important project for me. It’s the book I would have wanted when I was a twelve-year-old kid, and it’s the book I still want today.”

All of this author’s many space-themed books, even the quite technical and archly historical ones, come from that place of wonder. And images real or imagined go a long way towards deepening the impact words on their own can have. As a documentary film maker and media producer Bizony can appreciate that each have their place and time, an idea reflected early in the book in a quote from 1905: “First, inevitably, comes the idea, the fantasy, the fairy tale. Then, scientific calculation. Ultimately, fulfillment crowns the dream.” What makes the quote remarkable is that it is by a Russian, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the teacher, inventor, physicist, aviation engineer who is as much a father of rocketry as Goddard and Oberth. But even though the Russians had a long history of using art to stir the masses, and of course had been first, if only by three weeks, to put a man into space, their worries about operational secrecy trumped the propaganda value of art. The Americans saw this differently, and thus we have this most excellent book.

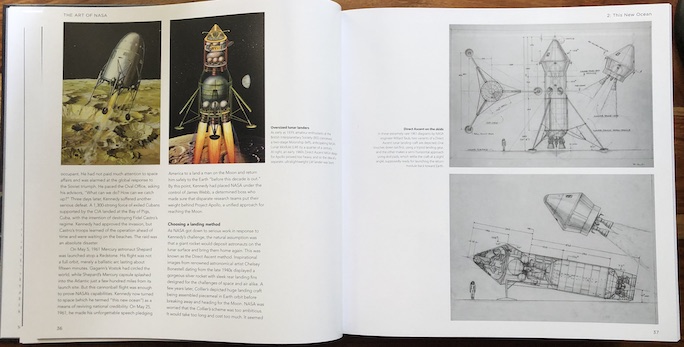

A landing vehicle. Would you have known that the illustrations on the left (which happen to be British) are more than 20 years older than the ones on the right? Those b/w diagrams are by NASA (1961) and sure look like engineering drawings and as if someone based them on actual science, but, no, it’s pure fantasy.

But before you even open it, acknowledge the elephant in the room: When the subject of space exploration comes up, is your first thought that it costs too much and that the money would be better spent fixing the innumerable problems on Earth? Did you ever have that same criticism of, say, the Departments of Transportation or Agriculture? Would it surprise you to know that NASA’s portion of the federal budget is just about as small a percentage as theirs and has never accounted for more than 2% since 1969? The highest ever was 4.4%, in 1966, in the run-up to putting a man on the moon. So . . . no need to lay a guilt trip on anyone.

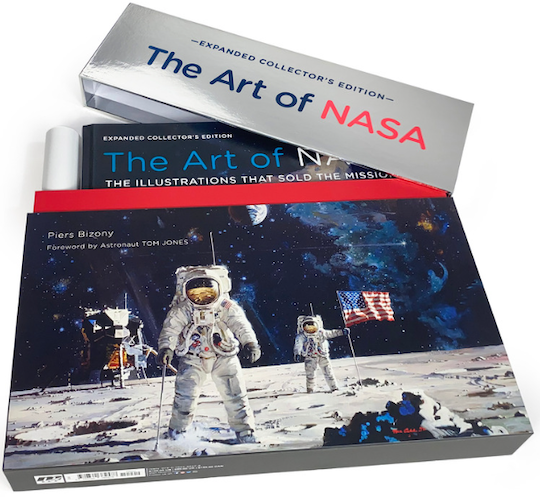

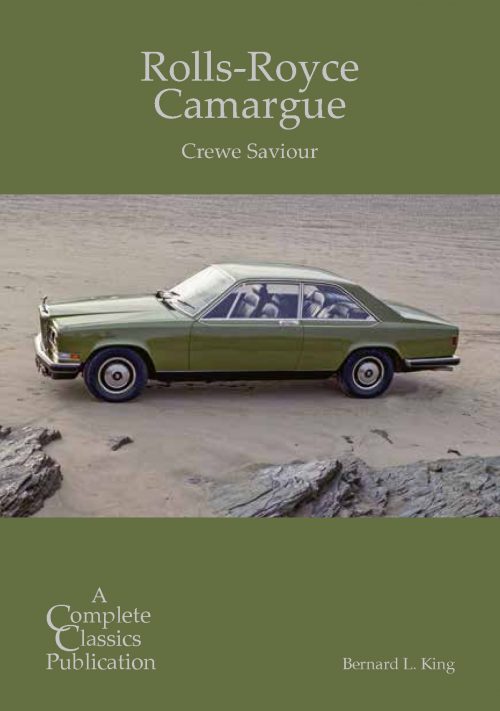

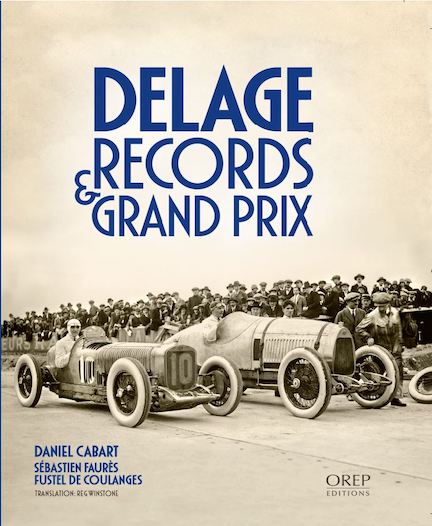

You can’t tell from the photo but the main type on the book cover is in raised lettering.

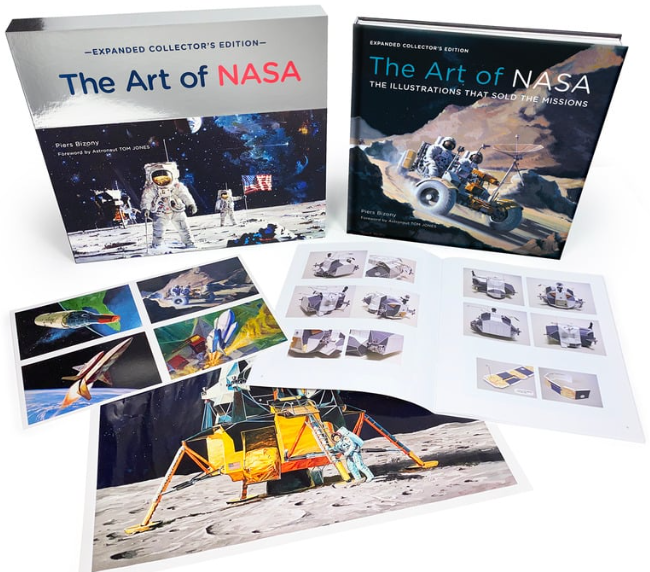

Speaking of budgets, whatever percentage the price of this book takes out of yours is probably also a trivial amount, even if as a single line item $100 sounds like a lot. We had intended to review the book when it originally came out in 2020, not least because it right away won an award by science fiction and fantasy magazine Locus in the Illustrated and Art Book category. It is still in print ($50) but just now came out as a premium collector’s edition with contents expanded by 32 pages and extra goodies that elevate the whole experience: a paper model of the Lunar Module you assemble yourself, a poster, four postcards, all in a fancy box. The Foreword is again by four-time Space Shuttle astronaut Tom Jones but specific to this edition.

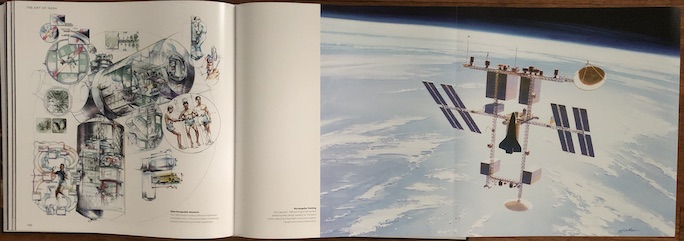

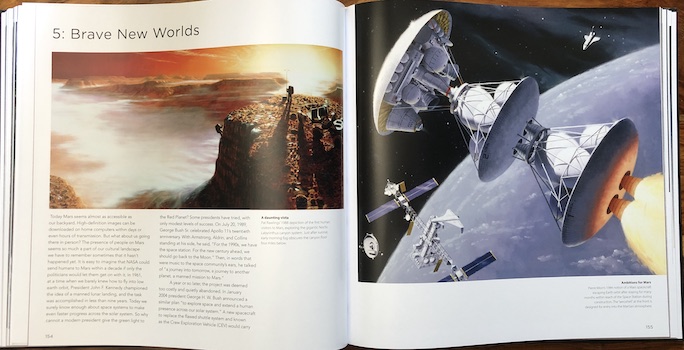

Befitting its subject the book is big, two feet wide when open with the two fold-outs adding another foot. The artwork is both by NASA and by its contractors, and it is sobering to realize how much of it is known to have been discarded over the decades—because the entities that commissioned it are not in the “business” of holding on to stuff that for all practical purposes was merely promotional material. Moreover, the paper artwork and paintings that are featured here were in their original application merely an interim and therefore disposable step (the final product being a photo or a printing plate of the artwork). Bizony credits a number of “citizen archivists” with saving originals from the shredder, and, in fact, is hopeful that a whole lot more is still squirreled away unknown and unappreciated in dusty attics.

Three feet of paper—can’t handle that in freefall so better sit down at a table. There are two such fold-outs but neither is a triptych that makes full use of the space.

Except for a few early examples the book covers space exploration from the American perspective beginning in the 1950s (the Russians do enter the picture once more in the context of the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project) and the six chapters are presented by mission type. There are almost as many illustrations as there are pages but there’s room for plenty of insightful and precise text. The captions in most cases state artist/year/client, and there is a good index.

Consider: “There hasn’t been a single fraction of a second over the last two decades without people in space, never fewer than three at a time.” In 2021 it was practically crowded: for 11 minutes, 19 people were in space, in three different vehicles! Space is so incomprehensibly vast it will forever remain the proverbial final frontier. Today we know a lot more about it than when Sputnik “the flying beach ball” first ventured out there but it helps immeasurably to be able to make the jump to a 1950s mindset when space exploration was the great unknown and untested. Today, there are still missions “to sell” the public on, and in many ways it’s harder now because the novelty of space has worn thin.

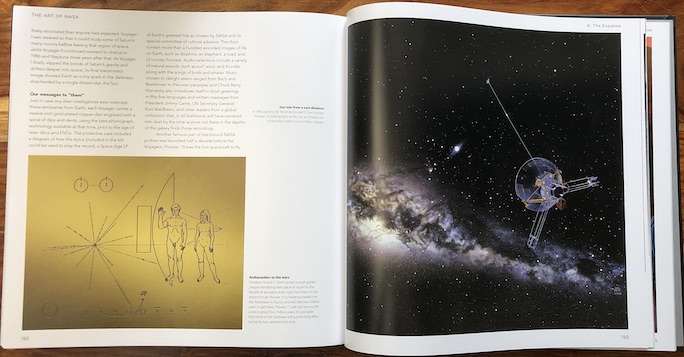

Let’s say you’re an alien. What would you make of the famous golden plaque that earthlings sent into space on Pioneers 10 and 11?? They’re going to different destinations and it’ll take #10 two million years to get there and #11 at least four.

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter