The Race to the Future: The Adventure That Accelerated the Twentieth Century

by Kassia St. Clair

by Kassia St. Clair

“There are no formalities to complete, no rules to trouble yourself with. You must simply set off from Peking and arrive in Paris. That is the challenge.”

—Le Matin editorial, 17 February 1907

Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, in common with myriad other politicians, have reveled in sneering at the institution which some Brits still call “Auntie”—the British Broadcasting Corporation. But it is the BBC that is indirectly responsible for this review because, last year, they adapted The Race to the Future for radio. How they condensed this extraordinarily wide-ranging book into just five fifteen-minute episodes is a minor miracle, but I knew that I had to read this book. Now that I’ve done so, I can confirm that it is terrific, especially in the way it transcends its notional subject matter.

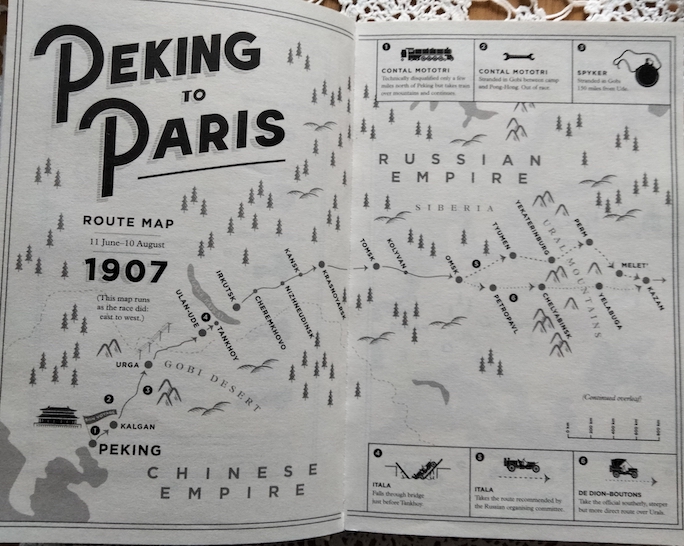

This 359-page hardback is about so much more than the Peking-Paris race which Le Matin had promoted in 1907, and the book’s subtitle is the clue: The Adventure That Accelerated the Twentieth Century. The 8000-mile race was unprecedented in its ambition, at a time when most of the world’s population had not even seen an internal combustion vehicle. The Ford Model T, the vehicle that democratized personal transport, did not appear until the following year, and society was still reliant on the horse, not horsepower. The race might only have had five entries, soon reduced to four, and the winning Itala might have enjoyed a lead of 2600 miles (really!) at two thirds’ distance, but as the author crisply observes, “The race had potent symbolic resonance as a harbinger of a new era of globalisation. . . . We are the inheritors of the world the Peking-Paris race helped create.”

This 359-page hardback is about so much more than the Peking-Paris race which Le Matin had promoted in 1907, and the book’s subtitle is the clue: The Adventure That Accelerated the Twentieth Century. The 8000-mile race was unprecedented in its ambition, at a time when most of the world’s population had not even seen an internal combustion vehicle. The Ford Model T, the vehicle that democratized personal transport, did not appear until the following year, and society was still reliant on the horse, not horsepower. The race might only have had five entries, soon reduced to four, and the winning Itala might have enjoyed a lead of 2600 miles (really!) at two thirds’ distance, but as the author crisply observes, “The race had potent symbolic resonance as a harbinger of a new era of globalisation. . . . We are the inheritors of the world the Peking-Paris race helped create.”

This book can be read purely as an account of the race itself, and the author even suggests that reading the chapters that separate the story of the race isn’t compulsory. But they elevate the book from a good read to a great one, because they cover a diversity of subjects including the geopolitics of 1907, fossil fuel’s toxic legacy, planned obsolescence, road safety, Thomas Edison’s insight into renewable energy, and lots more. Don’t think that Kassia St. Clair is another bien pensant commentator hectoring the reader into feeling guilty for the ‘Vette in the driveway, because she is the best of companions, with a wealth of stories to recount. And this reader fell under her spell.

This book can be read purely as an account of the race itself, and the author even suggests that reading the chapters that separate the story of the race isn’t compulsory. But they elevate the book from a good read to a great one, because they cover a diversity of subjects including the geopolitics of 1907, fossil fuel’s toxic legacy, planned obsolescence, road safety, Thomas Edison’s insight into renewable energy, and lots more. Don’t think that Kassia St. Clair is another bien pensant commentator hectoring the reader into feeling guilty for the ‘Vette in the driveway, because she is the best of companions, with a wealth of stories to recount. And this reader fell under her spell.

St. Clair’s writing is at its entertaining and colorful best when describing the extraordinary challenges and hardships that beset the competitors as they battled their way west across swamps, deserts, and mountains. As she describes it, “Days of mud; days of birch trees; days of boiled eggs and tea; days of grasses bending away in successive silver ripples as they passed.” The five teams had originally (and perhaps naively) decided to work together by running in convoy across the Gobi Desert and Siberia. But the narrative quickly changed from co-operation to selfishness, as Charles Godard and journalist Jean du Taillis learned the hard way when their Spyker expired in the desert. Was it the “civilized” Europeans who came to their rescue? Of course not, it was the Mongolian horsemen, “dressed in coats . . . decorated with geometric beadwork, and pillbox hats made from velvet and gold cloth.”

Kassia St. Clair writes with assurance and wit, making elegant asides on the essential absurdity of a race that was unprecedented in its ambition. She accomplishes the task of untangling the Machiavellian politics of a Russia already reeling from the 1905 “First Revolution” and she describes a Europe already on course for the self-combustion of 1914. We flatter ourselves how we learn from history to avoid repeating its mistakes and yet, as I read of the Holodomor in 1930s Ukraine and the tensions and distrust between Russia and her neighbors, all I could feel was déjà vu and a bitter aftertaste.

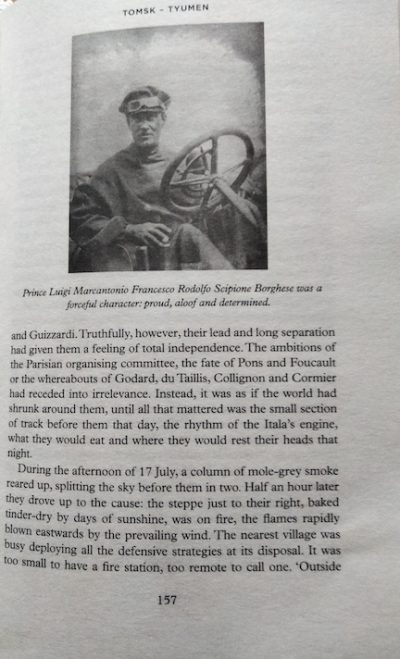

Il Principe.

I Ioved the descriptions of the often bizarre encounters the competitors had with the locals, none more than the conversation that took place en route to Nizhny Novgorod, when Prince Scipione Borghese’s 35/45 HP Itala expired. It was conducted in “a chimeric gabber composed of two living tongues and a scholarly one . . . ‘Grazie mille’ – ‘Arrivederci’ – ‘Do svidaniya!’ – ‘Salve’.”* I couldn’t help wondering how Brad or Ty from NASCAR would have communicated, if faced with similar circumstances. And I loved the dénouement, if over fifty years too late, of the Spyker’s suspiciously fast progress between Irkutsk and Kazan. The fact that the dastardly Charles Godard had achieved the vast distance “. . . under the cover of night by train and by boat” was only revealed by mechanic Bruno Stephan in 1963, when his conscience finally outweighed his loyalty to the Spyker marque. A word, incidentally, I do rather wish the author had used instead of the very 21st century “brand.”

Interest in rally raids (as the French term them) was re-stimulated in 1979 by the Paris-Dakar Rally, whose relatively laissez faire philosophy was a distant echo of the spirit of 1907. But thanks to the threat of terrorism the event moved first to South America and then to Saudi Arabia although “brand equity” (sigh) meant that, perversely, it kept its original and now wildly inaccurate name. The event involves pumped up Audis trashing virgin sand dunes while being shepherded by helicopters full of PR folk wittering about sustainability. What might Prince Borghese and Luigi Barzini say about that? My guess it’s the Italian for “vanity and folly”. . .

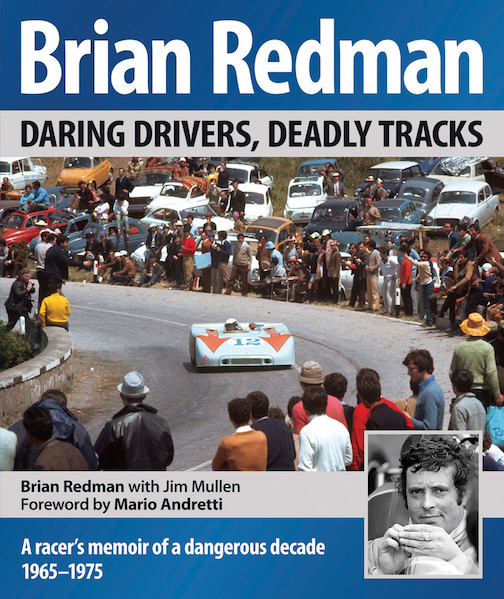

I read a lot of automotive books, but only very rarely would I recommend one to anybody who does not share my interest. For example, Jon Saltinstall’s book on the race career of Jackie Ickx makes compelling reading if you know the difference between a Porsche 356 and a 956 but if you don’t . . . well, perhaps not so much. Of the many books I’ve reviewed for Speedreaders, The Race to the Future is one of the few exceptions to this rule, in common with Tom Karen’s Toymaker and Crispian Besley’s Driven to Crime. It helps that the story of the Peking-Paris race has all the right ingredients—jeopardy, heroes and villains—with much of the action taking place in a world even more inaccessible now than it was then. But it’s the book’s scope, complemented by the writer’s accessible style, that makes it exceptional. For this reader it had the appeal of (for example) Jonathan Raban’s Badlands and Bill Bryson’s One Summer – America 1927, and that places it in rarified territory. Do read it, you won’t regret it.

The US edition by WW Norton/Liveright (2024) has a slightly different title (The Race to the Future: 8,000 Miles to Paris―The Adventure That Accelerated the Twentieth Century) and cover, and a separate ISBN 978-1-324-09491-3.

* Italian, Russian, and Latin

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter